The day Jesse Owens set four world records at Ferry Field

Eight decades have passed since Jesse Owens set four world track and field records on the University of Michigan athletics campus, a feat commemorated by a bronze plaque secured to a brick monument that also honors Michigan student-athletes who died in service to their country.

The engraved likeness of a smiling Owens catches your eye as you approach the southeast corner of the Ferry Field track. Inscribed on the plaque are his remarkable feats of May 25, 1935, when Owens set world records in the long jump, 220-yard dash and 220-yard low hurdles while tying the 100-yard dash mark at the championship meet for what was then called the Western Conference.

And if you close your eyes at that spot, you can almost imagine the roar of 5,000 fans on that glorious, hot, sunny afternoon. Tom Harmon, who would win the Heisman Trophy for Michigan in 1940, was among those cheering wildly. Harmon was on his recruiting visit that day and witnessed history. He later became friends with Owens, an Ohio State Buckeye who would be honored four decades later by his school’s fiercest rival.

Lucky day

Mike McGuire, the long-time Michigan women’s cross country coach and an All-America distance runner for the Wolverines, was on his recruiting visit on May 17, 1974, when Owens was being recognized. Don Canham, the former track coach and then the powerful, innovative athletic director at Michigan, had decided to bring Owens back and name him the honorary referee for that Big Ten outdoor track championship meet.

McGuire, wearing his Farmington (Mich.) High School letter jacket, was asked to pose for a photo with Owens by Chuck Davey, the father of his primary high school rival, Pat Davey of Birmingham Brother Rice. And the four of them stood together, McGuire to Owens’ immediate left, and smiled for the camera.

It remains a priceless possession, framed and hanging in the den of McGuire’s home, a black-and-white memory of the day a kid who loved track history got to meet it.

“I was excited knowing Jesse Owens was going to be there,” says McGuire, “and then the opportunity presented itself. My high school rival Pat Davey’s father, Chuck Davey, was a famous boxer at Michigan State and went on to fight for the world welterweight title. Chuck knew Jesse, and so he arranged for us to meet. It was a real thrill.

“Our conversation was just a real pleasant exchange. We chatted a bit, and he asked what events we did, and obviously we were a couple of skinny distance runners. I told him that I was going to be attending the University of Michigan, and Pat told him he was going to Tennessee. He wished us luck on finishing up our seasons and going on to college. It was a really, really cool experience.”

Adds McGuire, “I remember that as great of an athlete as he was, he was a great person. He was very gracious and had no airs about him at all. I was pretty wide-eyed because I was a track historian. I knew about Jesse Owens when I was in grade school.”

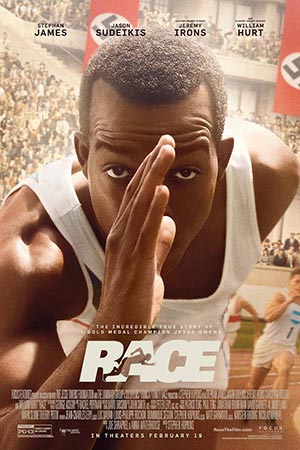

Race

Owens won four gold medals at the Berlin Olympics of 1936 and became an international star for both the accomplishment and the controversy his success sparked with Adolph Hitler, the leader of Nazi Germany, in attendance. The story is at the heart of the film Race, which opened Feb. 19.

Owens won four gold medals at the Berlin Olympics of 1936 and became an international star for both the accomplishment and the controversy his success sparked with Adolph Hitler, the leader of Nazi Germany, in attendance. The story is at the heart of the film Race, which opened Feb. 19.

But it was Owens’ record-breaking day at Michigan that is most dear to U-M fans who follow track and field.

“He was a tremendous ambassador for the sport of track and field,” McGuire says of Owens. “I’ve told the athletes I’ve coached about it because it was such a big thrill.”

Jack Harvey was an assistant track coach at Michigan then and was the head coach from 1975-99.

“I got to meet Jesse Owens at the meet,” says Harvey, “and he was such a quiet, nice guy. It’s amazing that he was never recognized for what he did in the way an athlete would be today. They say everyone’s feats become greater with the passing years, but he was that great.

“His performances on that day would place well even in today’s Big Ten meets. In fact, Jesse Owens’ long jump that day would’ve won this year’s Big Ten championship.”

Owens long-jumped 26 feet, 8-1/4 inches, soaring into the sand pit in front of his fellow competitors. That jump easily would have beaten the 24 feet, 9-1/4 inches posted by 2015 Big Ten champion Eze Emeka of Rutgers, and nobody has surpassed Owens’ jump in conference history, though Iowa’s Bashir Yamiui equaled it in 1997 and is listed as the co-record holder at 8.13 meters.

The distances of the races Owens ran have all changed and are now in meters rather than yards, but the program from the 1974 meet noted that Owens’ four records were still standing 39 years later, when all of those events were still being run at the same distances as in 1935.

Single finest day in track and field history

Making the feats that much more impressive was the fact that Owens had a sore back that caused him excessive stiffness and pain. Five days earlier, he’d tumbled down a flight of stairs after wrestling with a fraternity brother in Columbus. Owens had to be helped into the rumble seat of Buckeyes coach Larry Snyder’s car for the ride from their Ypsilanti hotel to Ferry Field.

Owens, in a story by John Hendershott of Track & Field News on the 40th anniversary of the record-setting day, said the team trainer “put a big swab of hot liniment on my back” and he required help just to pull on his sweat suit. Owens couldn’t stretch or jog, and he sat down to rest his back against a Ferry Field flagpole. He rested his weary head on his knees, and Snyder asked Owens if he wanted to be scratched from the competition.

Owens decided to run his first event, the 100-yard dash, and see how it went.

“When I got down on my marks and the starter said, ‘set,’ there was suddenly no more pain,” Owens told Hendershott. “It was gone. I couldn’t feel anything. I didn’t know why then and I don’t to this day.”

He ran the 100 in a world record-tying 9.4 seconds. Then he did the long jump before running 220 yards in 20.3 seconds and winning the 220-yard hurdles in 22.6 seconds for three new world records. He did it all in the span of 45 minutes.

Hendershott wrote: “Owens had turned in what is universally regarded as the single finest day in track and field history.”

Owens said, “I never expected anything close to what happened … The records were a launching pad for the Olympics.”

Transcending the rivalry

Harmon, on the 50th anniversary of the feat, told Earl Gustkey of The Los Angeles Times: “There was a tremendous excitement. It seemed like each race they’d announce, ‘World record!’ ‘World record!’ Geez, there was a tremendous excitement.

“It was a long time ago. But if you ever saw him run, one thing you never forgot about Owens was how fluid he was. He seemed to run just to the point of winning; he never seemed to have to shift into high gear. To do it as easily as he seemed to be running, that made it all the more amazing. It was quite a day. And it sure gave me a lot to talk about when I got back to Gary (Indiana).”Harmon would receive the ultimate tribute from Ohio State fans in 1940 with a standing ovation after accounting for 371 total yards, running for three touchdowns, passing for two touchdowns, making three interceptions, punting for a 50-yard average, and adding four extra points in a 40-0 rout in Columbus.

And Canham returned the favor to a Buckeye, inviting Owens to be the honorary referee and putting him on the cover of the 1974 Big Ten Outdoor Track Championships program — even though the program cover was done entirely in maize and blue. The plaque of Owens came after he died at the age of 66 in 1980.

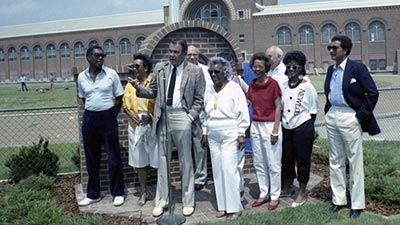

Don Canham with Minnie Owens and family at Jesse Owens plaque dedication (May 1985). (Image courtesy of mgoblue.com.)

“Don Canham knew that Jesse Owens had lung cancer and had it in the works to memorialize him,” says Harvey. “Owens’ wife and daughter came back — I believe it was in 1985 — to be honored at our last outdoor meet of the year.

“Canham knew Jesse and had great respect for the accomplishment. It was all Don’s doing. Being a track coach, he knew just how great Owens was. A guy from Ohio State did all of that in Ann Arbor and it was so significant that we should recognize it. Too much is made of these rivalries. It separates us, but we’re all in it for the same reasons.”

McGuire agrees.

“There’s that rivalry,” he says, “but those feats transcended the rivalry. We need to recognize it for what it was. It was great of Mr. Canham to initiate this. It’s fitting. What Jesse Owens did that day really transcended sports. It’s a no-brainer that we’ve done this to honor him.”

Eight decades later, it’s still a marvel to behold, a feat to cherish.

(This article originally appeared at mgoblue.com. Top image courtesy of U-M’s Bentley Historical Library.)

Peggy Totin - 1969

My dad, also an alum, was there when Jesse Owens broke all the records. He brought our whole family to Ann Arbor to see the the plaque. Dad had such a way with words, and he was able to bring the day to life with his stories. I can’t wait to see the movie.

Reply

Rich Weston - 1994

Visiting the plaque and running the Ferry Field track during my doctoral program at SPH were inspiring. On that “Day of Days” I believe that the 220 yard times, both the dash and the low hurdles, also set world marks in the 200 meter dash and 200 meter low hurdles. While American and British races used English measures, the rest of the world, including the Olympics, used metric measures. A 220 is a tad longer than a 200.

Reply

Roland Jersevic - 1974

I was fortunate to be the assistant announcer for that Big Ten Championship Meet in 1974 (we were the runners-up to Indiana) and had the opportunity to meet and shake hands with Jesse Owens…way cool! It was a once in a lifetime opportunity to go back to that most wonderful day of 1935 and momentarily feel the excitement-standing on the exact same place that it happened…Don Canham was right: Go Blue and Go Bucks on this day!

Reply

Craig Bloomer - 1980

I was a teammate of Mike McGuire when we were skinny kids in Farmington High School letter jackets. It is great to see another Michigan connection that led to an outstanding Women’s Cross Country team. Go Blue!

Reply

Michael Gasiciel - 1975 Catholic Central

What a great picture. Ran against Pat while at CC Remember he smoked the course at Rouge Park in Detroit at Catholic league meet. He ran 14:44 while our first 2 CC runners ran behind him at 15:03 and 15:10. I so much remember Mike always in the paper from Farmington hs. I loved it when Pat went out of state to Tenn with Stan Huntsman. I always hoped other all-staters would do that. I’ll always remember him running a state record at the time in’74 9:00.4 for 2 miles at the state meet. Cherish that photo always:)

Reply