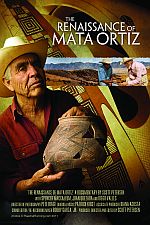

Scott Petersen ’92 is a filmmaker who stumbled on the amazing story of two strangers—an American anthropologist and an impoverished Mexican potter—who became friends through the potter’s extraordinary artwork. “The Renaissance of Mata Ortiz” is Petersen’s lively and fascinating documentary about an unlikely friendship and the transformation through art of an entire town. Michigan Today asked Petersen to take us behind the scenes of his movie.

MT: Give us a plot synopsis for this documentary. Who are the main figures, and what happens when they meet?

Juan Quezada is a self-taught artist who lives in a small town in northern Chihuahua called Mata Ortiz. Due to the timber and rail industries evaporating, Mata Ortiz was well on its way to becoming a ghost town in the 1950s. As a child, Juan would find ancient Paquimé ceramics in the mountains surrounding Mata Ortiz while searching for firewood. (The indigenous people around the Paquimé area disappeared prior to the Spanish coming to the Americas). He figured that if the ancient people made these pots, then all the materials must be available locally. He experimented for 15 years before he mastered pottery-making sometime in the early 1970s. Slowly, Quezada began to sell his pots to local traders and began to eke out a living.

In 1976, anthropologist Spencer MacCallum found three of Quezada’s pots in a second-hand store in Deming, New Mexico. MacCallum had purchased an ancient Paquimé pot at a yard sale in San Pedro, California, the previous year and thought that Quezada’s pots had similar features. Always up for an adventure, MacCallum set out for Mexico to find the artist. He found Quezada in Mata Ortiz, and after a few false starts, made a mutually-beneficial deal in which Quezada would be paid a monthly stipend and MacCallum would bring the pots to US galleries, universities and museums.As Quezada’s family saw his success, they began to learn from Juan and become artists in their own right. It soon spread to neighbors and now the village boasts several hundred potters. In 1999, Juan won the Premio Nacional, the highest award the Mexican government can give to a living artist.

(Image design by Chris St. George, photos by Raechel Running.)

Diego Valles is a young artist who has taken the traditional styles of Mata Ortiz pottery and incorporated contemporary designs to create fine art. In 2010, Diego won the Premio Nacional de la Juventud, the highest award the Mexican government can give to an artist under 30 years old (very similar to the award that Juan won in 1999). The odd thing about Diego is that he has an engineering degree, but decided to pursue art instead. Very few people in the area finish high school, so for someone to earn a college degree and then pursue a career in art is highly unusual. But Diego has established himself, at a very young age, as one of the top artists in the village.

MT: How did you first hear this story?

Initially, I saw a news story about Mata Ortiz. It sounded interesting, so I went down to the village just to check out what Mata Ortiz looked like and to see the pottery in person. Not long after, I attended a class that Juan taught at the Museum of Latin American Art in Long Beach, California. I don’t have any background in ceramics, but the class was too good of an opportunity to pass up. I brought my buddy in from Chicago to start shooting in the summer of 2007. We went down every summer for 2-3 weeks at a time for three years. I also shot a few events and such in the Los Angeles area.

Scott Peterson (Photo: Steve Ewert.)

MT: What about the story captivated you enough to invest all this time into telling it?

I like the idea of someone simply following their heart and doing what pleases them without financial considerations. I think most everyone can identify with that idea. It’s an adventure and it takes you places that you never knew existed. Both Juan and Spencer were simply doing what they did best which ended up paying off for both of them.Ultimately, there are only two stories: (1) a person goes on a journey and (2) a stranger comes to town. But it’s really the same story, it just depends on where you live! The interconnectedness of the individual journeys of Juan and Spencer were fascinating. Thjat Spencer just happens to find an ancient pot at a yard sale and then finds a Juan pot a year later is a simply amazing coincidence. And, of course, the only reason Juan made pots was that he found very similar ancient pots in the mountains as a kid!I was also attracted to the cross-cultural element of two people from different places working together and creating an economy that has transformed an entire region. Also, as a filmmaker, I’m impressed with the ability of so many people in one small area who are able to create great art and make a living doing it.Creatively and visually, Chihuahua is incredible. The desert light is naturally beautiful and it looks amazing on faces. The desert is a character in itself; life is cyclical and I tried to show that with some of the time-lapse shots of the landscapes, mountains, clouds, etc.

MT: Why do you think this story matters, both to you on a personal level and for others?

This story illustrates that if you work hard enough at what you love (and have talent), you can become successful. That sounds like such an “American” story, but of course Juan’s not American! I’m marketing the movie to university ceramics/art departments and I’m sure that instructors hear complaints from students that they don’t have enough money to buy the right paint or equipment or whatever. Well, Juan didn’t have anything, except time and his own desire to create. His family had little money and less food, but he found a way to maximize his time. It’s a good lesson for artists to not let excuses get in the way. I’m hoping that teachers will use it to inspire their students.On a more general level, it also shows how one person (or two) can make a huge difference. It’s a horrible pun, but it’s almost like “It’s a Juan-derful Life.” Had Juan decided not to make pots, Mata Ortiz would probably cease to exist today. Had Spencer decided against finding the artist, Mata Ortiz certainly wouldn’t be what it is today.

MT: Did making this movie change you?

I don’t know if it changed my perception of the world specifically, but it certainly solidified my belief in learning things for yourself. A lot of people are afraid to travel to Mexico. While a lot of people have been killed as part of the drug/cartel war in Mexico, very few Americans have been harmed who haven’t been involved in the drug trade in some way. But you could just as easily be a victim of random crime in the US! I mean, how many people have returned from their trip to Mexico with their heads intact? The world can be a dangerous place, but it’s not as dangerous as many people think.One thing I learned was that it is extremely time-consuming to make a movie in a foreign language. My Spanish skills are marginal (I took a lot of French back in the day). Had the movie been entirely in English or if I was fully bilingual, I could have finished it at least a year earlier. I had to get all the English interviews transcribed and all the Spanish interviews translated and transcribed. Then, I had to subtitle all the Spanish interviews. That was even before I started actually cutting the movie. I’m not complaining, but it added an extra challenge and I simply had to allow for the time to do it.