Introducing Brazil’s “inhospitable wildness” to U-M

Portuguese Version (Global Michigan)

When University of Michigan President Mary Sue Coleman visits Brazil this month, she will be renewing ties that date far back in U-M’s history, all the way to a young naturalist who explored the Amazon ecosystem nearly 50 years before Theodore Roosevelt’s famous expedition on the River of Doubt.

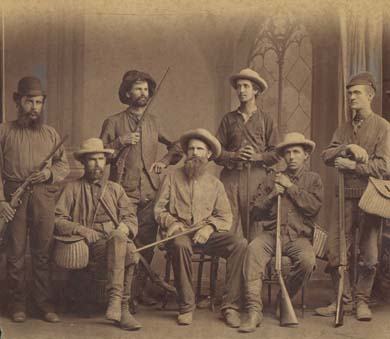

Joseph Beal Steere and his team of explorers. (Image courtesy of U-M’s Bentley Historical Library.)

Born in 1842, Joseph Beal Steere was raised by Quaker and Presbyterian parents on the family’s farm near Adrian in Michigan’s Lenawee County. He grew up fascinated by birds and animals. A well-to-do older cousin in Ann Arbor—a lumber man named Rice Beal—spotted the boy’s intelligence and helped to pay his way through college.

On the U-M campus, Steere haunted the zoology collections as a student volunteer and pored over a new book, The Naturalist on the River Amazons, by the British explorer Henry Walter Bates. Bates’ account of his 11 years amid the teeming species of the Amazon rainforest—curly-crested toucans, great river turtles, scarlet-faced monkeys, boa constrictors—was one of the great travel yarns of the era, and it sparked an extraordinary ambition in Steere.

Mapping the living landscape

The budding naturalist earned his bachelor’s degree in 1868 and added a law degree in 1870. Then he booked passage to South America on a small sailing schooner. (Again, his cousin Beal helped with the financing.) Becalmed in the Sargasso Sea, Steere dipped a nail-studded board into the water and scooped up a patch of seaweed crawling with tiny marine creatures. Thus, an extraordinary adventure in scientific collecting began.

Steere set off into the Brazilian forest soon after Charles Darwin’s The Origin of Species made its first impact among naturalists. Earlier natural explorers had gathered zoological and botanical specimens chiefly to put them on display. But Steere’s generation of biologists was more interested in working out the implications of Darwin’s revolutionary theory. They wanted to know exactly where species lived and how they were distributed in their habitats. They were not just collecting oddities. They were mapping the living landscape.

The landscape where Steere now found himself was far more ominous than the woodlands and meadows of his native Midwest. Under the vast green canopy he was struck by the pervasive “silence and gloom.” He wrote, “The impression deepens on longer acquaintance . . . The few sounds of birds are of that pensive or mysterious character, which intensifies the feeling of solitude rather than imparts a sense of life and cheerfulness.” Early in the morning and again at nightfall, crowds of monkeys overhead would make “a most fearful and harrowing noise,” he reported, “under which it is difficult to keep up one’s buoyancy of spirit. The feeling of inhospitable wildness is increased tenfold under this fearful uproar.”

Insects and mammals and birds, oh my!

But the spookiness of the forest did nothing to dampen Steere’s zeal for exploration and study. He steadily amassed trunkloads of specimens and shipped them back to Ann Arbor one by one—insects, plants, birds, mammals. He met indigenous peoples, made notes on their lore and languages, and bartered for samples of their tools and weapons.

Steere spent a year-and-a-half criss-crossing Brazil by riverboat and on foot, then crossed into Peru for more collecting in the Andes. Next he went north to Ecuador and back to Peru. In Lima, apparently inexhaustible, he boarded a steamer bound for China. There his collecting continued, followed by explorations of habitats in Formosa (now Taiwan), the Philippines, and the Dutch East Indies (now Indonesia). Steere was the first Western naturalist ever to study some areas of the Philippines. And the contacts he made there helped to create U-M’s strong bonds with the island nation.

Steere as a young professor. (Image courtesy of the U-M Bentley Historical Library.)

Meanwhile, back at home, Ann Arbor’s naturalists were counting and cataloging Steere’s trunkloads of specimens. All told, they found he had gathered some 60,000 animals, birds, and insects and well over 1,000 plants. Until then, the University’s natural collections had been drawn chiefly from the Great Lakes. This huge international addition to its holdings—soon named the Beal-Steere Collection to honor both the financier, Steere’s cousin, and the collector himself—spurred the construction of the University’s first free-standing museum, apparently the first of its kind at a public university. And even before Steere reached home, the Regents awarded him an honorary PhD degree and appointed him an instructor in biology.

Friends for science

“The expedition had been a tremendous success,” his colleague Frederick Gaige would write later. “Zoological specimens included birds, mammals, reptiles, fishes, shells, corals, and insects. His botanical specimens showed plants, woods, flowers, and fruits. Anthropological material embraced a great number of specimens of pottery, weapons, implements, ceremonial pieces, clothing. He had gathered a great store of firsthand observations. Everywhere he had made friends—friends for science, for his native country, for his institution, and for himself.”

After five years of study abroad, Steere finally returned home. At the University he rose quickly to full professor. He directed the work of the museum and taught for 16 years, returning twice to Brazil and once to the Philippines. He retired young to a farm outside of Ann Arbor, though he maintained close ties with the University and his former students for the rest of his life. He died at the age of 98 in 1940.

harvey miller

One of Steere’s relatives was William Campbell Steere who headed botany at ann Arbor until 1960 when he went to Stanford where I did the PhD with him. His son Billy Jr. headed Pfizer drugs and rather recently retired. WCS went to the directorship of New York Botanical Garden where he retired as director emeritus. There should be more about him in Michigan archives.

Reply

Paula Newquist

Joseph Beal Steere is my great grandfather. I have recently been trying to find information about him. It was fun to find this website. I’d love to see some of the collection. Is there a website that shows some of them?

Reply

Deborah Holdship

U-M’s Bentley Historical Library website, http://bentley.umich.edu, holds a collection of your great grandfather’s papers (http://quod.lib.umich.edu/b/bhlead/umich-bhl-85831?rgn=main;view=text) but you would have to visit the library on U-M’s North Campus in Ann Arbor to access them. I suggest you call 734-764-3482 to speak to a librarian. In addition, you will find several digital resources via U-M if you visit http://umich.edu and type Joseph Beal Steere in the search box. Quite a few links appear. Best of luck!

Reply

Roberta Gundlach - Indiana University

I would like to buy a copy of both these photo. The portrait and the expedition. This is my third great grandfather and we are so proud.

Roberta Gundlach

813-628-7839

Robertagundlach@me.com

Reply

Deborah Holdship

I will connect you to the folks at the Bentley once the U reopens from the holiday! How cool that you are related.

Reply