Archaeologist Richard Redding, BA ’71/PhD ’81, digs adventure. For a living.

His work has taken him to Egypt, Tanzania, Israel, and China. He’s traveled to Turkey, Syria, Soviet Armenia, and Iraq. He’s been chased. Arrested a couple of times. In 1973 he stumbled upon a secret military base in Iran.

“I play the harmless idiot as best I can,” Redding says of his dealings with foreign officials who feel he’s overstepped his bounds. “I’ll just say, ‘See my rocks?'”

Redding has discovered far more than rocks in his role as associate research scientist at the University of Michigan Kelsey Museum of Archaeology. He also is the chief research officer and archaeozoologist at Ancient Egypt Research Associates (AERA), a nongovernmental organization that runs a field school near the Giza Pyramids. Its current focus is excavating an ancient urban site about 400 meters south of the Sphinx.

“I always liked to collect broken skulls and other things that disgusted my mother,” Redding says of his lifelong fascination with animal bones. And though he came to Michigan to study chemistry, he soon changed course and earned undergraduate degrees in anthropology and geology, followed by a doctorate in archaeology and biological sciences.

Today he excavates, examines, and catalogs items that illuminate life beyond the pyramids. In fact, Redding is not very interested in the pyramids at all. It’s the men who built them that hold his fascination: how they lived, worked, and organized themselves in the site that he and his colleagues have named the Lost City of the Pyramid Builders. They discovered it beneath a modern-day garbage dump.

“I’d rather find one good house floor than a tomb full of stuff,” Redding says. “You get 10 times the amount of information on how people lived from one house floor than you get from a burial site.”

One Man’s Junk…

Surprisingly little research has been done on the “house floors” and people who lived and worked at the base of the pyramids, Redding points out. Just go to the graduate library at U-M, if you don’t believe him, and stand in front of the Egypt section. “You’ll see four and five cases of books on the Old Kingdom, and almost all if it is focused on the pyramids, temples, and tombs,” he says. Even the excavation of areas where people lived tend to focus on the temples, he notes.

“That’s like trying to understand American culture by excavating the Arlington Cemetery and the Mall in Washington, D.C.”

Redding began to focus on the ancient workforce during a 1984 excavation of a village site along the Nile Delta. In 1989, he joined a team of researchers led by AERA President Mark Lehner (who is likely familiar to viewers of the Discovery Channel) to “humanize the pyramids.” They set about excavating sites near the base of the tombs built during the fourth dynasty spanning the reigns of the emperors Kufu, Khafre, and Menkaure. What they’ve found to date is a cache of evidence into early organizational behavior—from project management to industrialized production.

“You start with these little tiny fragments, these little pieces of bone,” Redding says, “and you follow the evidence to learn something about how the Old Kingdom functioned.”

…Is Another Man’s Treasure

In 1991-92, Redding’s team targeted a modern-day garbage dump and began to unearth the footprint of the lost civilization. Their work continues to expand a decade later, revealing a huge complex of buildings and barracks covering about five hectares. The site was home to an estimated 8,000 workers.

Each discovery leads to new questions, new digs, and new answers: What would it take to actually feed 8,000 people? How many animals do you have? How many people do you need to herd the animals? If you have an Old Kingdom economy, is it limited by land or by labor?

“I’m really into the intellectual puzzle of it,” Redding says. “I’m trying to stretch the data to the point that it almost breaks. I like to start with a hypothesis and test it to death.”

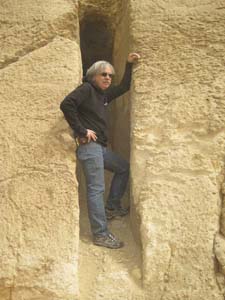

A team from AERA explores a residential site at the base of the pyramids. (Image courtesy of Richard Redding.)

Testing his hypotheses to death has led to the discovery of livestock pens that once held cattle, sheep, and goats. (Redding dubbed this area of his site the OK Corral, as in “Old Kingdom” Corral.) Now the AERA field teams are exploring nearby sites where livestock were probably butchered and processed on a large scale, as well as factory-like bakeries designed to mass produce enough bread to feed this expansive workforce. These are just a few early examples of industrialized processes that predate the modern assembly line.

As AERA’s digs unearth more and more pieces of the Lost City of the Pyramid Builders, a picture begins to emerge about the men who lived there and the leaders who oversaw them. Crews of 2,000 men were divided into working gangs of 1,000. Gangs were broken into smaller units called Zas. Each had a specific name, and they regularly signed their work. Excavation at one mortuary temple indicates one half was built by the “Friends of Menkaure”; the other by the “Drunkards of Menkaure.” And lest you think the drunkards produced sub-standard work, Redding says, “Both sides are good. There is no evidence of any difference in the craftsmanship on either side.”

What a Town Without Pity Can Do

It likely took some 5,440 men and 20 years to move all the blocks required to build one pyramid, Redding says. And the work was grueling, yes, but it was seasonal, temporary, and well-planned. Scribes in charge of the crews would deliver their quota of men each year. These workers often were farmers who would leave their fields during flood season to set aside agriculture in favor of construction. Once the annual flood season ended, the workers would go home to plant and harvest, with the expectation they would return to the barracks, and their respective gangs, same time next year. While on the site, it appears they were under strict control by way of an enclosure wall.

“You’ve got 8,000 young men between the ages of 16 and 24 … I imagine there were problems keeping order,” Redding says.

So far, the digs have revealed a pair of long-term residential sites, dubbed “Eastern Town” and “Western Town” where single-family homes likely housed the “townies.” In Western Town, artifacts–specifically the signed seals used to cover jars and other vessels–indicate these were the homes of the managers and more affluent members of the society. There is “the Scribe of the Royal Box” and “the Scribe of the Royal School.”

Animal bones, pottery shards, and even a single leopard tooth lend valuable clues about the aristocrats, craftsman, stonecutters, and quarrymen who worked year-round as well as the specialists who carved statuary, melted copper, and made tools. Evidence of a harbor and grain silos offer additional information about the early landscape, travel, and trade.

There are even signs of early sustainable behavior. Study indicates the bricks and timbers, used to build the workers’ barracks, were “recycled” into other buildings once the barracks were abandoned upon the pyramids’ completion.

So while these magnificent structures continue to hold the public’s fascination, Redding finds “the pyramids get smaller and smaller for me every year.” He has an answer—or at least a well-researched hypothesis—to address each myth or mystery that arises.

“The reason the builders came to Giza is a rock formation that could support the weight of the pyramids,” he says, noting early engineers (not aliens) knew from experience the massive structures would collapse under their own weight if not supported by a decent foundation. “The site at Giza provided a great base,” he says.

And the reason the pyramids are mystically aligned with the constellation Orion?

“The rock formation’s strike runs from the northeast to the southwest. These pyramids are built right along the strike—right at the densest, strongest, heaviest foundation you can get.”

Foundation for the Future

One of Redding’s proudest accomplishments is his part in the development of AERA’s field school, whose experts have trained some 400 Egyptian archaeologists to date.

“We, at AERA, have taken a major step in empowering local archaeologists so they can participate as full partners in the study of Ancient Egypt,” Redding says.

The school is an integral part of AERA’s main facility within walking distance of the Great Pyramid. A renovated villa houses a library and archive, a dormitory, and a kitchen serving an international crew of researchers from Britain, Sweden, Germany, Italy, Portugal, the U.S., Canada, Poland, and of course, Egypt. Redding spends a few months each year on site, teaching and working with fellow archaeologists. He also leads alumni tours organized by the U-M Alumni Association.

Not surprisingly, the most vexing aspect of his work is coping with challenges presented by modern man. Currently AERA’s team is negotiating with local bureaucrats who don’t seem to share the organization’s passion for finding answers that lie beneath the 21st century garbage dumps and parks used by area residents. One unexplored part of the site likely holds critical information that will help complete the picture of life in the Lost City of the Pyramid Builders. Unfortunately, it’s buried beneath a soccer field that is off-limits to AERA and its archaeologists.

“We’ve gotten land and funding for a new field to be built about a kilometer away,” Redding says. “But they won’t move. I have to say, that is the bane of our existence.”

Luckily Redding has an endless supply of patience and plenty of hypotheses to keep him busy for now.

“We could be here for the next 50 years and barely scratch the surface,” he says.

Nancy Middleton - 1978

so….where are the women?

Reply