Ebbets Field: April 15, 1947

More than any other figure in American history, Jackie Robinson stood alone.

Unlike Abraham Lincoln, he had no army to support him.

Unlike Martin Luther King Jr., he had no movement behind him.

But he did have Brooklyn Dodgers general manager Branch Rickey, JD ’11—and that made all the difference.

“Rickey needed Jack as much as Jack needed Rickey,” said Robinson’s wife, Rachel.

(Story continues below video.)

“A Matter of Fairness” is a 2009 production by Metrocom International for the Michigan Law School.

Bigger than baseball

In April 1947, when Robinson stepped into the batter’s box at Ebbets Field wearing No. 42 for the Brooklyn Dodgers, virtually no institution in American life was officially and completely integrated. Not the schools, not the government, not the military–and certainly not baseball, where resistance seemed greatest. Breaking the color barrier in Major League Baseball not only preceded all these advances, it helped make them possible.

But if you didn’t look closely you would never predict Rickey, an erudite and professorial Michigan Law School graduate, would be the one to pursue the “Great Experiment” any more than you’d predict Robinson would be the best candidate to carry it out.

Like Robinson, there was more to Rickey than met the eye. Politically, he was ultra-conservative. Topping Rickey’s list of social evils were Franklin Roosevelt, communism, and welfare. But he believed in fairness above all and often performed pro bono legal work for African-American defendants he felt had been wrongly accused. This predisposition was a product of both his education and his religious background. It was a trait that would resonate throughout Rickey’s dealings in both business and baseball.

More than a game

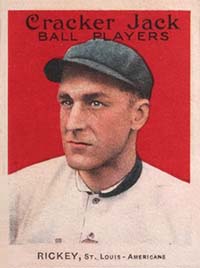

On Dec. 20, 1881, Wesley Branch Rickey was born in Lucasville, Ohio. He enrolled at Ohio Wesleyan in 1901, where he played catcher and coached before getting “a cup of coffee” in the major leagues with the St. Louis Browns and the New York Highlanders, now called the Yankees.

His refusal to play on the Sabbath—and his .239 batting average—were enough to convince him to change careers. He enrolled at Michigan in 1909, earning his law degree in two years and coaching the U-M baseball team until 1913. He excelled at both.

Legendary sports writer Red Smith once wrote, “Rickey was a giant among pygmies. If his goal had been the United States Supreme Court instead of the Cincinnati Reds, he would have been a giant on the bench.”

“If he ever played ‘Jeopardy,'” athlete-turned-television announcer Joe Garagiola said, “he would have swept the board.”

It’s clear Rickey could have applied his considerable talents to business, law, or the clergy. So one might wonder why he spent his life in baseball. Sometimes he did, too.

“I completed a college degree in three years,” Rickey once remarked. “I was in the top 10 percent of my class in law school. I’m a doctor of jurisprudence. I am an honorary doctor of law. Now, tell me why I just spent four mortal hours today conversing with a person named Dizzy Dean?”

In a more thoughtful moment, he once asked himself why “a man trained for the law devotes his life to something so cosmically unimportant as a game.”

Perhaps because he recognized he could do more good for his country in baseball than he could in law, business, or even the church. One thing is certain: Rickey never treated baseball as just a game.

The great experimenter

For all he might have done, Rickey seemed born to be a general manager in Major League Baseball. And when he moved to the Brooklyn Dodgers in 1942, his new players quickly learned that Rickey was as cheap as he was smart.

Said Dodgers’ outfielder Gene Hermanski: “Mr. Rickey had a heart of gold—and he kept it.”

Negotiations with players from his alma mater were no exception. When Rickey coached Michigan, he recognized freshman George Sisler’s talent immediately. After Sisler earned his degree in engineering in 1915, he embarked on a Hall of Fame career, then accepted Rickey’s offer to work as a scout. In that capacity, Sisler signed Michigan outfielder Don Lund, ’45, to a minor league contract. Lund played the 1946 season (with Robinson) for Brooklyn’s top farm team in Montreal. When he was summoned to Ebbets Field for contract talks, he and Rickey talked about Michigan “for an hour or so,” he said.

“Mr. Rickey finally asked me what kind of contract I wanted, and I said I wanted a major league contract with a $7,500 bonus,” Lund told me. “He said, ‘Sure, no problem.’ Right there I knew I’d blown it. Branch Rickey never would have said yes so fast unless he was getting the better deal.”

Brooklyn second baseman Eddie Stanky had a similar experience. “I got a million dollars worth of free advice,” he said, “and a very small raise.”

The right aide of history

It is tempting to cast the African-American experience as a slow but upward trajectory since the Civil War. It’s tempting, but wrong. Consider the rise of Jim Crow laws and the Ku Klux Klan at the turn of the century.

In the 80 years between the end of the Civil War and World War II, the most significant legal change in the status of African Americans was entirely negative. It came in the form of Plessy v. Ferguson (1896) in which the U.S. Supreme Court coined the phrase “separate but equal,” legalizing segregation. Rickey would have studied the case in law school, a little more than a decade after the ruling came down. His Michigan Law classmates would have included a number of African-American and female students, and the obvious wrong-headedness of this ruling struck him immediately.

As World War II ended, Rickey felt an urgency to act on the right side of history–and he believed the national pastime was the place to start.

“It took a big man to do what he did,” Negro League legend Buck O’Neil told me, and he knew of what he spoke. In 1962, O’Neil would become the first African-American coach in the major leagues. “A lot of guys were against it, see. It could have killed Rickey in baseball if this thing had blown up.”

Here’s to You, Mr. Robinson

The real question was: Whom to sign?

Rickey wasn’t looking for the best player, but for the player best suited to survive the rigors of an arduous year. And the man he chose certainly wasn’t the most skilled athlete, and he was by no means a pacifist.

In 1944, while a captain in the U.S. Army, Robinson had been court-martialed for refusing to move to the back of the bus (11 years before Rosa Parks would ignite the Montgomery Bus Boycott by doing the same thing). This act of defiance didn’t turn Rickey off, but impressed him. “I don’t like silent men when personal liberty is at stake,” he once said.

So in August 1945 Rickey invited Robinson to his office for a historic meeting. He wanted to sign Robinson to Brooklyn’s Montreal-based farm team and bring him up to the major leagues in a year or two. But he needed to know if Robinson could survive long enough to establish a foot-hold. Could he put up with Southern hotel clerks, racist waiters, and cut-throat runners who would want to “haul off and sock you right in the cheek?”

“Mr. Rickey,” Robinson asked, “Are you looking for a Negro who is afraid to fight back?”

“I will never forget the way he exploded,” the athlete wrote later.

“Robinson, I’m looking for a ballplayer with guts enough not to fight back.”

After thinking it over, Robinson answered Rickey quietly and deliberately. “Mr. Rickey,” he finally said, “I’ve got two cheeks. If you want to take this gamble, I promise you there will be no incidents.”

“You’re asking the man for quite a bit,” O’Neil said of the arrangement. “To be that strong you had to know exactly what it meant for a black man to play in the major leagues. Lucky for us, Jackie did.”

So did Rickey. In signing Robinson first, the visionary executive didn’t make the obvious choice. He made the bold one–and the smart one.

Harrison Ford portrays Branch Rickey in the film “42: The Jackie Robinson Story” (April 2013).

A movement begins

Some critics accused Rickey of bringing Robinson up solely to win games and fill seats. No doubt the competitive advantages of breaking the color barrier appealed to the Dodgers’ president and general manager. But Rickey’s deeply held belief in social justice, especially in light of the incredible risk he was taking with his own career, suggest higher motives. “It’s not a move,” he would say. “It’s a movement.”

Filmmaker Ken Burns, who spent almost a decade researching his comprehensive documentaries on the Civil War and baseball said, “I feel in my gut that Rickey knew, beyond any business considerations, that [integrating baseball] was good for mankind.”

The day Robinson stepped into the batter’s box on Ebbets Field for the first time transcended baseball, said Burns. “The first real progress in race relations after the Civil War, sorry to say, was Jackie Robinson. Jackie Robinson was the man who continued the work Lincoln laid out.”

George Will, Pulitzer Prize winner and author of numerous baseball books, including Men at Work: The Craft of Baseball, concurred. “The most important black person in American history is Martin Luther King Jr. A close second, I would argue, is Jackie Robinson.”

Martin Luther King Jr. himself once stated: “Jackie Robinson made it possible for me in the first place. Without him, I would never have been able to do what I did.”

Robinson often said that very thing about Rickey.

“I owe him a debt of gratitude,” Robinson said. “I will always speak out with the utmost praise for the man.”

“Don’t ever forget,” said Buck O’Neil, “when you say Jackie Robinson to say Branch Rickey too, see, because you couldn’t have one without the other.”

In 2009, with contributions from principal owner of the New York Mets Fred Wilpon, ’58, former Chicago Cubs owner Sam Zell, ’66, and Major League Baseball, the Branch Rickey Collegiate Professorship of Law was established at the University of Michigan.

John U. Bacon was a writer and associate producer on the documentary “A Matter of Fairness.” Chris Cook directed, wrote, and produced the film. David Lampe was executive producer.

Richard Friedman, the Alene and Allan F. Smith Professor of Law featured in the podcast “Breaking Racial Barriers,” is an expert on evidence and U.S. Supreme Court history.

nancy beebe - 1973

Excellent article on Rickey – what an incredible man.

Reply

Gordon Ridley - 1974 MHA

Great article about a great man. My grandfather, Clarence Ridley ’14 Engineering, talked about Rickey and Sisler. He was in a pick up game with Sisler on the mound for the other team. Clarence told me that he was the only player on his team to reach base, and only because Sisler hit him with a pitch!

Reply

Dr. Ed Kornblue - UM '49-'52, B.A. 1968, NYU, D.D.S. 1956

Two marvelous men, meant for eachother, playing out the story of the evolution of equality in America. We should be proud of the influence that Michigan and those educated and connected to U of M, had on these two men.

It is both, a touching and very meaningful story in our country’s history.

Reply

Ivy Austin

Great short film, story and photos. It is an inspiring Michigan legacy contribution to the American ideal for the ages. Thank you for compiling the story.

Reply