Heart to heart

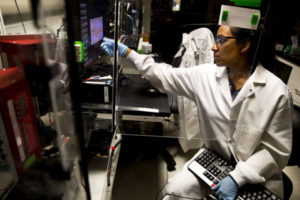

Stacy Ramcharan, a doctoral student in chemical engineering, uses a computerized system to layer polymer fibers, forming a scaffold for growing cells into artificial tissues. (Image: Joseph Xu.)

The University of Michigan is partnering on an ambitious $20 million project to grow new heart tissue for cardiac patients.

The new research center has been awarded to Boston University, with strong partnership from U-M and Florida International University.

A heart attack creates scar tissue, and the heart never returns to full function. But for every person, we could create a living patch that a surgeon could stitch in. It’s very audacious,” says Stephen Forrest, who leads the nanotechnology aspect of the project and is U-M’s Peter A. Franken Distinguished University Professor of Engineering.

The project is a National Science Foundation Engineering Research Center. These five-year grants are typically renewed for another five years, so the researchers are looking at a 10-year timeline to go from the current state of tissue engineering to working, implantable heart tissue.

“Heart disease is one of the biggest problems we face,” says David Bishop, director of the new center and a BU professor of electrical and computer engineering and physics. “This grant gives us the opportunity to define a societal problem, and then create the industry to solve it.”

The living patches the researchers are developing would consist of heart muscle cells, blood vessels to carry nutrients in and waste out, and optical circuitry to make the heart muscle cells beat in synchrony.

Already, researchers in the lab have been developing ways to structure cells in scaffolds that mimic particular organs and grow blood vessels into artificial tissues. But typically, working implants have been static, biodegradable materials such as artificial windpipes that the body gradually replaces with tissue. Working tissue, like heart muscle, would need to be responsive as soon as it was implanted.

Translating breakthroughs

Engineering Research Center grants are extremely competitive, with only four of more than 200 applicants receiving an award in 2017. These centers are designed to work directly with industry to translate breakthroughs along the way out of the lab and into health care. Just producing a more true-to-life “heart on a chip” could aid the pharmaceutical industry in developing better treatments for problems such as arrhythmia.“In order to produce the heart tissue, the team intends to start with an artificial scaffold that mimics the 3-D structure of heart tissue. Joerg Lahann, U-M professor of chemical engineering, will work with the team building the flexible polymer scaffold, as well as on the attachment and monitoring of cells within that framework.

“Michigan is pleased to lend expertise to the development of implantable heart tissue, which could improve and extend so many lives,” says Alec Gallimore, the Robert J. Vlasic Dean of Engineering. “Our faculty members are leaders in nanotechnology and in developing materials that support and interact with living cells and tissues, two areas that are critical to the project’s success.”

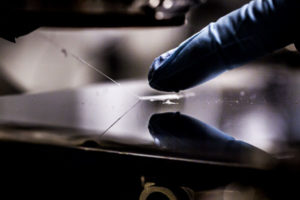

The 3-D scaffold will initially be peppered with nanometer-sized gold patches that act as attachment points for protein fragments, called peptides, which will then serve as anchors for the cells. They will be printed onto the gold patches using a technique developed by Forrest and Max Shtein, U-M associate professor of materials science and engineering. This method, called organic vapor jet printing, was initially invented for mass-producing electronic devices.“The adaptation of this technology to biological systems represents a radically new step,” Forrest says.

U-M will receive $2.8 million for these contributions.

Growing muscles

Ramcharan and her colleagues in Lahann’s lab will help design and produce a polymer-protein construct that mimics the 3D matrix connecting the cells in human heart muscle. (Image: Joseph Xu.)

Christopher Chen, the center’s director of cellular engineering and BU professor of biomedical engineering, will lead the effort to grow heart muscle cells on the scaffold and infuse the tissue with blood vessels. Meanwhile, Alice White, director of nanomechanics and chair of the BU mechanical engineering department will work closely with Arvind Agarwal, FIU professor of mechanical and materials engineering, to produce an artificial nervous system that uses light to synchronize the heartbeat in the tissue.

“It’s humbling to have the opportunity to work on something that could really be a game changer,” Bishop says. “If we succeed, we’ll save a lot of lives and add meaningful years for many people.”

In addition to the technical thrusts led by Forrest, Chen and White, Thomas Bifano, professor of mechanical engineering and director of BU’s Photonics Center, will direct imaging.

Along with the core partners, Harvard Medical School, Columbia University, the Wyss Institute at Harvard, Argonne National Laboratory, the École Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne in Switzerland, and the Centro Atómico in Argentina will offer expertise in bioengineering, nanotechnology and other areas.

Forrest is also the Paul G. Goebel Professor of Engineering, and a professor of electrical engineering and computer science, materials science and engineering, and physics. Lahann is also a professor of material science and engineering, biomedical engineering, and macromolecular science and engineering. Shtein is also an associate professor of chemical engineering, macromolecular science and engineering, and art and design. Gallimore is also the Richard F. and Eleanor A. Towner Professor, an Arthur F. Thurnau Professor, and a professor of aerospace engineering.