To your health

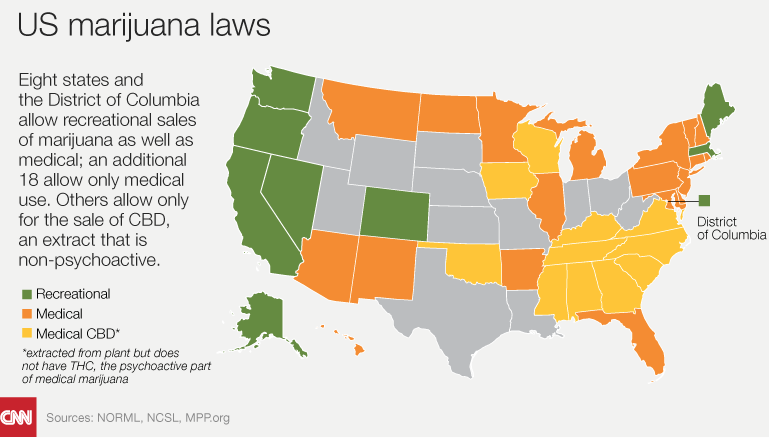

We are in the middle of a medical and social revolution. Cannabis, which once was prohibited federally and in all 50 states, is now approved for medicinal purposes in 30 states. And just in the last few months Oklahoma — that’s right, Oklahoma — became the latest state to approve broad access to cannabis. Moreover, nine states – Washington, Oregon, California, Nevada, Hawaii, Colorado, Massachusetts, Maine, and the District of Columbia — have decriminalized marijuana.

In November 2018, Michigan residents will vote whether or not to legalize recreational use of cannabis, having approved medical use in 2008. Recent polls indicate strong support for passage.

Across America, support for legalized marijuana has been steadily growing. In 2000, 31 percent of Americans supported legalization, according to a Gallup poll. By 2009, support had risen to 44 percent, and in 2017 it was reported at 61 percent. Support for medical marijuana is now nearly ubiquitous: More than 94 percent of the U.S. population say they support medical marijuana use. Entrepreneurs like it too. In 2016, cannabis sales totaled $6.7 billion. Sales are expected to double every two years going forward.

Overview

Cannabis is one of the world’s oldest cultivated plants. It is an annual, dioecious flowering herb indigenous to central Asia and the Indian subcontinent, but it grows almost anywhere. There are three different cannabis species – Cannabis Indica, Cannabis Sativa, and Cannabis Ruderalis. All three are considered subspecies of the sativa category. Cannabis also is known as Hemp, although this term often refers only to varieties of cannabis cultivated for non-drug use — including fibers and oils. Cannabis plants have been crossbred to produce selected properties like maximum levels of fibers, oils, or specific chemical constituents, such as ∆9–Tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), the principal psychoactive component of the plant.

Cannabis is one of the world’s oldest cultivated plants. It is an annual, dioecious flowering herb indigenous to central Asia and the Indian subcontinent, but it grows almost anywhere. There are three different cannabis species – Cannabis Indica, Cannabis Sativa, and Cannabis Ruderalis. All three are considered subspecies of the sativa category. Cannabis also is known as Hemp, although this term often refers only to varieties of cannabis cultivated for non-drug use — including fibers and oils. Cannabis plants have been crossbred to produce selected properties like maximum levels of fibers, oils, or specific chemical constituents, such as ∆9–Tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), the principal psychoactive component of the plant.

The terms “marijuana” and “cannabis” often are used interchangeably, particularly in the United States, but they are separate entities.

- Marijuana generally refers only to parts of the cannabis sativa plant, or derivative products that contain substantial levels of THC.

- Cannabis is a broad term that describes the organic products derived from the cannabis sativa plant (e.g., cannabinoids, marijuana, and hemp) that exist in various forms.

Cannabis’ active ingredients

Cannabis contains more than 500 known chemical compounds, most of which have not yet been characterized for biological activity. While many of the cannabis constituents also can be found in other plants, it is only the cannabinoids that are unique to the cannabis plant. Many cannabinoids act on cannabinoid receptors located throughout the body and brain. This “endocannabinoid system” participates in a variety of physiological processes, including appetite, pain-sensation, mood, memory, fertility, and pregnancy; and during pre- and postnatal development. This system also contributes to exercise-induced euphoria.

Major cannabis chemicals

- Cannabinoids — 70 different cannabinoids have been identified. THC is the most common. THC is responsible for cannabis’ psychotropic effects. Other cannabinoids, like cannabidiol (CBD), have a similar chemical structure as THC, but exhibit different biological effects with virtually no psychotropic potential. Other cannabinoids include cannabigerol (CBG) and tetrahydrocannabivarin (THCV). Cannabinoids present in their so-called non-active acid-form, and it is only during heating to high temperatures (vaporizing, smoking, or baking) that these chemicals transform into their more active compounds.

- Terpenes — Chemicals that give cannabis its distinct smell(s). There are more than 120 different terpenes in cannabis. (Drug search dogs are trained to recognize specific terpenes to find cannabis.) Terpenes have a wide range of known biological effects, such as anti-inflammatory, antibiotic, or analgesic. Some terpenes also may be involved in regulating and/or changing the effects of THC and other cannabinoids.

- Other cannabis chemicals –Different strains of cannabis produce a different spectrum of chemicals. Some may only be produced by very specific strains, or the same constituents may be present but in different relative amounts. As a result, the medicinal properties of cannabis strains can vary widely. Because of the large number of chemicals, it is difficult to study how the chemical composition of a cannabis strain relates to its effect on different medical conditions.

History

One of the first references to “medical cannabis” appears to be made by Chinese Emperor Fu Hsi(circa 2900 BC). He noted that cannabis was a very popular “medicine” for regulating both “yin”and “yang.”Later, circa 2700 BC, according to legend, the Chinese emperor Shen Nungdiscovered marijuana’s healing properties, along with those of ginseng and ephedra.The earliest written reference to the medicinal use of marijuana dates to about 1500 BC in the Chinese Pharmacopeia,the Rh-Ya.

The Ebers Papyrus(Egypt), dated about 1500 BC, also mentions various medicinal properties of cannabis. For example, it described how to use cannabis as a suppository to relieve hemorrhoids.

A sacred ointment made of kaneh-bosm(cannabis) – is mentioned in the Book of Exodus(30:22-25) in 1450 BC. Jesus Christ used this holy anointing oil, which contained some six pounds of cannabis, extracted into about six quarts of olive oil, along with a variety of other fragrant herbs. Those anointed were drenched in this mixture. It is worth considering that the word “Christ”means “the anointed one.”

Traces of cannabis pollen were found in the tomb of Ramses II, who died in 1213 BC. Also, records indicate that cannabis was used in India around 1000 BC to treat sluggish temperament and unemotional or apathetic behaviors. Healers also used it to treat eye inflammation and to “cool” the uterus during pregnancy.

In the Middle East, in the 7th century BC, religious texts mentioned cannabis as the most important among 10,000 medicinal plants. The first detailed written work explaining the properties of hemp in India dates to the 6th century BC to the Sushruta Samhita,Ayurvedic Medical Treatise, an ancient Sanskrit text on medicine and surgery.

Early adopters

Chemical analyses of plant residues in tobacco pipes from Stratford-upon-Avon and environs, dating to the early 17th century, suggest William Shakespeare used cannabis (as well as cocaine). Scientists examined pipe bowls and stems obtained on loan from the Shakespeare Birthplace Trust. They analyzed residue from 24 pipe fragments and found cannabis residue in eight samples, nicotine in at least one sample, and evidence of Peruvian cocaine in two samples.

The Jamestown, N.Y., settlers brought marijuana to North America in 1611, and throughout the colonial period, hemp fiber was an important export.

George Washington’s diary entries indicate he grew hemp at Mount Vernon for about 30 years. According to his written ledgers, Washington was particularly intrigued by the medicinal use of cannabis. His writing indicates that he was growing cannabis with a high THC content. Here is an entry from Washington’s diary, dated 1765 (Source: Library of Congress).

Marijuana added to U.S. Pharmacopeia (1850)

By 1850, cannabis had made its way into the United States Pharmacopeia. This is the official public document listing all prescription and over-the-counter medicines. The document listed marijuana as a treatment for neuralgia, tetanus, typhus, cholera, rabies, dysentery, alcoholism, opiate addiction, anthrax, leprosy, incontinence, gout, convulsive disorders, tonsillitis, insanity, excessive menstrual bleeding, and uterine bleeding, among other conditions.

Massachusetts first state to outlaw cannabis

The early 1900s marked a high tide of prohibitionist sentiment in America. Between 1910-16 initiatives to prohibit alcohol appeared on several state ballots as did attempts to regulate such morals issues as prostitution, racetrack gambling, prizefighting, and oral sex. Amidst this profusion of vices, Indian hemp (aka cannabis) was a minor afterthought. Nevertheless, states began to ban cannabis production and sales. In 1911, Massachusetts became the first state to ban production and sales of cannabis. Other states passed similar laws, not due to any widespread use or concern about cannabis, but as regulatory initiatives to discourage future use.

By 1933, marijuana became the target of government control, pushed by outlandish (and false) stories in the newspapers owned by William Randolph Hearst. It turns out Hearst had financial interests in the lumber and paper industries, and he sought to eliminate competition from similar hemp-produced products. Almost daily, Hearst published stories regarding the dangers and horrors of cannabis and successfully linked it to opium addiction among young people. By the end of 1936, all 48 states had enacted laws to regulate cannabis. Its decline for medical purposes was hastened by the development of aspirin, morphine, and other opium-derived drugs, all of which helped to replace marijuana in the treatment of pain and other medical conditions in Western medicine.

1970 Controlled Substances Act (CSA)

In the late 20th century, a rising tide of interest focused on the control, regulation, sale, and distribution of addictive drugs. More than 200 state-enacted drug laws appeared, both to protect consumers and public health. This effort was fueled by social, medical, governmental, law enforcement, and business interests, but it did little to resolve the country’s perceived “drug problem.”

In an attempt to remedy this, President Richard Nixon signed the Controlled Substances Act (CSA) in 1970. The goal was to consolidate federal drug laws into one single statute. Under the CSA, drugs, substances, and chemicals used to make drugs are classified into five distinct categories, or “schedules,” depending on the drug’s acceptable medical use and its potential for abuse or dependency. Marijuana was listed as a Schedule I drug, considered to have “no accepted medical use and a high potential for abuse.”

- Schedule I drugs – Heroin, lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD), marijuana (cannabis), 3,4-methylenedioxyamphetamine (ecstasy), methaqualone, and peyote

- Schedule II drugs – Vicodin, cocaine, methamphetamine, methadone, hydromorphone (Dilaudid), meperidine (Demerol), oxycodone (OxyContin), fentanyl, Dexedrine, Adderall, and Ritalin

- Schedule III drugs – Tylenol with codeine, ketamine, anabolic steroids, testosterone

- Schedule IV drugs – Xanax, Soma, Darvon, Darvocet, Valium, Ativan, Talwin, Ambien, Tramadol

- Schedule V drugs – Cough preparations with less than 200 milligrams of codeine or per 100 milliliters – Robitussin AC, Lomotil, Motofen, Lyrica, Parepectolin

Pharmaceuticals and cannabis-based medications

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has licensed several drugs based on cannabinoids. Dronabinol,the generic name for synthetic THC, is marketed under the trade name of Marinol®and is clinically indicated to counteract nausea and vomiting associated with chemotherapy and to stimulate appetite in AIDS patients. A second synthetic analog of THC, Nabilone (Cesamet®),is prescribed for similar indications. In July 2016, the FDA approved Syndros®,a liquid formulation of dronabinol, for the treatment of patients experiencing chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting who have not responded to conventional antiemetic therapies.

In June 2018, the USDA approved a cannabis-based drug, Epidiolex,a cannabidiol twice-daily oral solution approved for use in patients 2 years and older to treat two types of epileptic syndromes. Epidiolexwill become available in the U.S. this fall. It is possible that once on the market, Epidiolexcould be prescribed for additional conditions. This is called off-label useand is a common practice with many medications.

Cannabis, medicine, and science

Proponents of medical marijuana claim it can be a safe and effective treatment for symptoms of cancer, AIDS, multiple sclerosis, pain, glaucoma, epilepsy, and other conditions. They cite peer-reviewed studies, prominent medical organizations, major government reports, and the use of marijuana-as-medicine throughout world history. They cite no observable downsides.Opponents of medical marijuana argue it is too dangerous to use and lacks FDA approval. They contend existing legal drugs make medical-marijuana use unnecessary. Marijuana is addictive, they say, and leads to harder drug use, interferes with fertility, impairs driving ability, and injures the lungs, immune system, and brain. They say medical marijuana is a front for drug legalization and recreational use.

Proponents of both views cite scientific evidence to support their positions.

A PubMed search of published research on cannabis is astonishing. Using the search word “cannabis” resulted in more than 18,253 peer-reviewed articles. There were more than 27,896 articles for the term “marijuana,” and more than 4,000 articles for the term “medical marijuana” (as of July 12, 2018). It is difficult to see a clear consensus regarding the potential health benefits and risks of cannabis and its constituent cannabinoids because various researchers rely on quantitative methods (interventional, correlational, survey, clinical, and experimental), qualitative methods (theory, ethnographic, narrative), and/or mixed-method research designs.

To me, two important questions emerge regarding medical marijuana:

- Can cannabis relieve health problems, i.e., can it be a medicine?

- Are there negative effects of cannabis use?

These two questions are embedded in a web of social and political concerns, particularly the nonmedical use of cannabis. These issues spill over into the medical marijuana debate and obscure the real state of scientific knowledge.

In next month’s column, I will summarize and analyze what we know about the medical use of cannabis. I will emphasize evidence-based medicine, based on rigorous scientific analyses, as opposed to belief-based medicine (derived from judgment, intuition, and beliefs untested by rigorous science). Stay tuned.

References

- Bennett, C. “Was Jesus a stoner?” High Times Magazine, Feb. 10, 2003.

- Bennett, C., McQueen, N., “Cannabis and Christ: Jesus used marijuana.” Adapted from: Sex, Drugs, Violence and the Bible: The Pagan Origins of the Judaic and Christian Traditions (Volume 2, The New Testament and Related Literature).

- Birch, E.A. “The use of Indian hemp in the treatment of chronic chloral and chronic opium poisoning.” The Lancet, 1889; Vol.133, Issue 3422, p 625.

- Borchardt, Debra, “Marijuana sales totaled $6.7 billion in 2016.” Forbes.com, Jan. 3, 2017.

- Cohen, P.J. “Medical marijuana, compassionate use, and public policy: Expert opinion or vox populi?” Hastings Center Report, 2006; 36(3):19.

- Deitch, R. “Hemp — American history revisited: The plant with a divided history.” 2003. Algora Publishing, New York, NY.

- Theguardian.com, “Jesus healed using cannabis.” Jan. 6, 2003.

- History of marijuana as medicine – 2900 BC to present.

- Kennedy, M.C. “Cannabis: Exercise performance and sport. A systematic review.” Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport, 2017;20(9):825.

- Mack, A., Joy, J. “Marijuana as medicine? The science beyond the controversy (2000).” Washington (DC): National Academies Press (U.S.).

- Marijuana and Public Health

- Medicinal Marijuana Association

- Segal, B. “Perspectives on drug use in the United States.” Haworth Press (1986, New York, NY)

- Sun, X., et al. “A recipe for disaster or treatment?” Yale Journal of Biology and Medicine, 2015; 88(3):265.

- Thackeray, F. “Shakespeare, plants, and chemical analysis of early 17th-century clay ‘tobacco’ pipes from Europe.” South African Journal of Science, 2015; 111(7/8).

- Thackeray, J.F., et al. “Chemical analysis of residues from 17th-century clay pipes from Stratford-upon-Avon and environs.” South African Journal of Science, 2001; 97:19.

- U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration — DEA Program: Cannabis Eradication.

- Wade, L. “Biomedical research. Canadian registry to track thousands of pot smokers.” Science, 2015; 348(6237):846.

![Marijuana depicted as a Chinese ideogram [pictorial symbol] of plants drying in a shed.](https://michigantoday.umich.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/89/2018/09/image004-277x300.png)

Philip Richardson - 1966

If we were able to look at these data objectively without all of the hidden political agendas I believe humanity would benefit.

Reply

Marjorie Scott - 1959

‘Very informative article about a topic we all need to understand and know more about to make informed decisions.

Reply

W A Wentz - 1976 - PhD

Thank you for this article and those that follow I have a rare condition (PLS) that creates muscle problems and pain and recently began using small amounts of CBD oil (oral). It seems to allow me to sleep much better and reduces my need for pain medication. But finding any guidance on use, side-effects etc. has been difficult. Even my doctors are asking me for information on my perception of results and any studies I might have found. More research and clinical observation seems necessary.

Reply

Linda Baumann - 70, 75

An informative article. Looking forward to the next one.

Reply

Michel Haaring - 1986

Very nice article @michigantoday !

Looking forward for the next month’s column.

Reply