Both beautiful and problematic

Todd Duncan (Porgy) and Anne Brown (Bess), 1935. (Photo courtesy of the Ira & Leonore Gershwin Trusts.)

It has been called the first great American opera, made all the more significant by being set in a black American community and performed by black artists at a time when black culture was exoticized by the country’s white majority.

Over the following 80 years, Porgy and Bess (1935) became one of the most celebrated American works of the 20th century, while simultaneously igniting controversy every time it was performed due to its themes, characterizations, and appropriative nature — an opera about black Americans created by white artists. Porgy and Bess, both beautiful and problematic, forces us to confront these issues.

Remarkably, despite its fame and undisputed place in American music history, this monumental work has never had a definitive score. Over the last three years, the editors at the University of Michigan’s Gershwin Initiative have been hard at work righting this wrong, creating a new edition of the opera. The newly edited score restores material often cut in past productions. Most exciting, the score now includes an onstage band in Act II that has not been performed since the opera’s preview in Boston in 1935 (prior to its first production that year on Broadway).

The road to a critical edition

Established in 2013, the Gershwin Initiative is a historic partnership between U-M and the Gershwin family estates, who have granted our scholars unprecedented access to all of the Gershwins’ personal papers, compositional drafts, and original manuscript scores, in order to create the first-ever critical edition of their works. Now in its fourth year, the George and Ira Gershwin Critical Edition is making excellent progress, with its first completed scores coming to fruition.

This past September, An American in Paris was given its world premiere in Paris by the Cincinnati Symphony, while the Atlanta Symphony presented the first U.S. performance and the BBC Proms will present the United Kingdom premiere of the work in July 2018, performed by the BBC Symphony Orchestra. Along with Rhapsody in Blue, these initial editions are scheduled for publication in 2018. While the critical score of Porgy and Bess remains several years away, the performance materials being developed now will receive their official world premiere in 2019 at The Metropolitan Opera in New York.

Editor-in-Chief and professor of musicology Mark Clague is enthusiastic about the project, its scope, and its successes. “I’m enormously proud of the work we are doing on campus,” says Clague, “and I can think of no place better suited than the University of Michigan to bring the necessary depth of expertise, reflection, and careful devotion not only to the Gershwins’ legacy, but to their relationship to America’s cultural heritage as a whole.”

At the head of this laborious undertaking is volume editor Wayne Shirley, a former specialist in the Music Division at the Library of Congress and an authority on 20th-century American music and the Gershwins in particular. Before the establishment of the Initiative, Shirley had already been at work for two decades preparing this new edition of Porgy and Bess.

Making the new 720-page edition of Porgy and Bess is a daunting task for the Gershwin Initiative, due to both its length and the complex web of archival source materials associated with it. SMTD students are involved with every step of the process. Coordinated by Managing Editor Jessica Getman, they work closely with Shirley to confront numerous discrepancies between the current rental score and the instrumental parts, as well as between that score and George Gershwin’s original manuscript. The published piano-vocal score is also problematic. It was prepared from the composer’s sketches and not his orchestrated manuscript, leading to yet more inconsistencies. This amounts to a quagmire of conflicting sources through which the editors must wade to construct an accurate edition.

Performing the opera has long been challenging; the instrumental parts in particular contain many wrong notes and material cuts that frustrate performers. It was, in fact, the need for a new score of Porgy and Bess that served as the initial catalyst for the U-M Gershwin Initiative.

Ultimately, two full-score editions will be produced: one will be the critical score, heavily annotated with editorial commentary intended for research use, and the other will be a clean score and parts, optimized for performance. An updated piano-vocal score and a new choral score will be created as well, which will mark the first time in the opera’s history that the piano-vocal score has the same number of measures as the full score.

The ‘American folk opera’ and its controversies

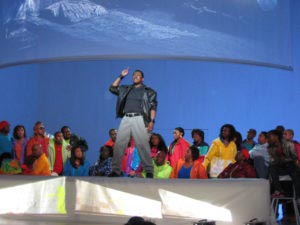

U-M SMTD professor Daniel Washington has played Crown in productions of “Porgy and Bess” internationally, including this opera comique production in Paris.

Porgy and Bess was the product of a collaboration between George Gershwin and Southern Renaissance author Dubose Heyward, whose libretto was based on both his 1925 novel Porgy and the successful Broadway stage adaptation co-written with his wife Dorothy two years later. In addition to the Heywards, George’s brother and main collaborator, Ira, also made contributions to the lyrics. Authorship of the work is credited to both the Gershwins and the Heywards.

Musically, Porgy and Bess is a kaleidoscope of styles, referencing European operatic traditions, Tin Pan Alley tunes, and black-American vernacular idioms of jazz, spirituals, and blues; Gershwin’s idiomatic voice is characterized by the synthesis of these different musical languages. The music also shows him at the height of his compositional abilities, having spent three years in intensive study with composer and teacher Joseph Schillinger. As Gershwin’s voice was silenced by his untimely death in 1937 at the age of 38, Porgy and Bess represents his most advanced and ambitious compositional achievement.

Despite an initially lukewarm critical reception, Porgy and Bess has since emerged as a cornerstone of the American operatic repertoire, and produced such Gershwin standards as “Summertime,” “I Got Plenty o’ Nuttin’,” “My Man’s Gone Now,” and “It Ain’t Necessarily So.” The presence of distinct songs in the work led early critics to debate whether Porgy and Bess was really an opera or a musical.

The opera tells the story of the African American inhabitants of an impoverished tenement near the docks of Charleston, S.C., called “Catfish Row.” The story itself has been a source of controversy concerning the depiction of southern black life by white authors.

ICYMI: This clip showcases preparations for the recent performance and symposium.

It’s complicated

Although Gershwin made an extended trip to Charleston to attend church services and absorb black musical idioms, he elected to compose his own original “spirituals” rather than incorporate existing African American melodies, and this drew criticism in light of the work’s subtitle, “An American Folk Opera.” The fact that the composer claimed “folk” authenticity in his original music remains problematic. However, the opera — and its music in particular — resonates with a broad sense of American identity, making “American Folk Opera” a complex description that warrants scholarly consideration.

John Bubbles (Sportin’ Life) and Anne Brown (Bess), 1935. (Photo courtesy of the Ira & Leonore Gershwin Trusts.)

Since its premiere, Porgy and Bess has come under fire for its treatment of black themes and black music. In a 1936 review in the black journal Opportunity, Hall Johnson wrote, “What we are to consider . . . is not a Negro opera by Gershwin, but Gershwin’s idea of what a Negro opera should be.” In other words, Porgy and Bess was a caricature of black artistry. In The Crisis of the Negro Intellectual (1967), Harold Cruse, a professor in U-M’s Department of Afroamerican and African Studies (DAAS), attacked this aspect of Porgy and Bess. He argued that the work “must be criticized from the Negro point of view as the most perfect symbol of the Negro creative artist’s cultural denial, degradation, exclusion, exploitation, and acceptance of white paternalism.” Cruse went so far as to call for a permanent boycott of the opera.

The opera’s characters themselves have likewise drawn criticism, as they engage in racial stereotypes that echo blackface minstrelsy. Naomi André, associate director at U-M’s Residential College and associate professor in DAAS and Women’s Studies, has studied the opera and its complex characters in depth.

“Porgy and Bess is a double-edged sword for many people,” says André. “It has heartfelt melodies and terrible stereotypes that reference minstrel images, it shows an inner depth to its main characters and also dooms them to terrible outcomes.”

André explains that the opera “is a product of its original time in the early 1930s during the Depression and Jim Crow, but it also has had continual resonance up through the present as race relations in the United States remain complicated.” (André’s book Black Opera: History, Power, and Engagement is forthcoming from University of Illinois Press, and includes a chapter on Porgy and Bess.)

Celebrating black operatic talent

Emeritus professor George Shirley as Sportin’ Life in a 1998 production of “Porgy and Bess” mounted on the floating stage at the Bregenz festival in Austria.

One of the defining facets of Porgy and Bess is that the Gershwin family maintained a contractual requirement that in staged productions, all black characters in the cast and chorus must be performed by black singers; in non-staged performances, the chorus need not adhere to this restriction. This has made Porgy and Bess an important vehicle for celebrating black operatic talent.

SMTD Emeritus Professor of Voice, George Shirley, a Grammy-winning operatic tenor and the first black tenor to sing at the Metropolitan Opera, has played the role of Sportin’ Life many times and has a pragmatic viewpoint on the opera’s depictions. “As in Cavalleria Rusticana or Alban Berg’s Lulu, Porgy and Bess reflects the realities of life that exist amongst communities where poverty of circumstance dictates morality to a considerable degree, as well as the mode of survival,” says Shirley, “a fact no different for the black community than for any other.”

Shirley went on to say that bringing this work to the stage at U-M provides “opportunities to address the lack of works that could serve to balance the negative views of blacks.” He simultaneously praised Porgy and Bess for its dramatic power and musical excellence.

The power of a perfomance

Porgy and Bess is a product of 20th-century American culture. But how will its life and resonance change in the 21st century? Mark Clague sees not only a contemporary relevance, but an urgency in its themes.

“Porgy and Bess should be antiquated, but it’s not,” says Clague. “Its dramatic momentum comes from interpersonal conflict in the context of the impossibility of justice. In the opera, the residents of Catfish Row are all black; all the police are white. Cell phone videos today show an undeniable reality that justice is not equally available to all Americans because of race and class. The same is true onstage in Porgy and Bess, and thus the opera remains a contemporary call to action for all who witness it.”

Barry Stulberg - 56;59

Please keep me posted as to when this opera will be performed and also when it might be recorded to disc. Thanks.

Reply