“Fresh, springy, vital … ”

Their reunions take place strictly during the odd-numbered years (wink, wink). They share a legacy steeped in satire, sarcasm, and scandal. They are the past and current staffers at Gargoyle, U-M’s 109-year-old humor magazine. And forever they will agree on one thing: “What this place needs is a good yuk.” (Gargoyle, November 1950.)

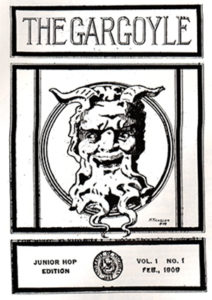

It is fitting that the man who created the Gargoyle went on to found a company that introduced canned chicken chow mein and its catchy jingle — LaChoy makes Chinese food swing American — to the masses. Lee A. White, AB ’10/MA ’11, kicked off the first issue of Gargoyle as a half-humor, half-literature-and-art magazine.

White’s opening letter to readers revealed which half the editor most favored. The only thing missing was the rimshot.

“We herewith offer to appreciators of good literature the first number of a literary magazine,” White wrote in February 1909. “We have tried to make it fresh, springy, vital. If our readers do not justly estimate the result, if they think we have fallen many degrees below our aim, we shall regret their lack of judgment.”

A wacky world view

For more than a century, aspiring humorists have used the Gargoyle to skewer university life and report on world events — from the suffragette movement to the Vietnam War and well beyond. The magazine staff has proudly poked the metaphorical middle finger in the eye of the U-M administration as often as possible, lighting the fuse and waiting for a reaction. Housed in the Stanford Lipsey Student Publications Building at 420 Maynard, the Gargoyle has forever been the cool Fresh Prince to The Michigan Daily’sbuttoned-up Carlton. It also is one of the country’s longest-publishing college humor magazines.

“They have so many clubs at Michigan,” says John Wambaugh, BS ’99, Gargoyle editor in 1998-99. “If you like to eat fried chicken and ski, there will be 20 other people on campus who also like to eat fried chicken and ski. Gargoyle is a group of people who all look at the world the same way. Most of us felt we were alone in how we looked at things until we walked into that office.”

The jokers

The early years of the Garg,as it is affectionately known, were not particularly notable. Some limericks, some cartoons with silly captions. Even White, when looking back at those early issues, admitted “I can’t see much in them that amuses me.”

The next editor, W.A.P. John, ’16, figured out the formula to grow readership.

“I quickly learned that we had to have some ‘burning issue’ as a continuing butt of our satire and so-called humor,” he wrote for the 90th anniversary remembrance book, Gargoyle Laughs at the 20thCentury.One topic was the unattractiveness of the female co-eds on campus, “and amid their shrieks of objection our circulation began to climb.” The following year, the writers satirized the construction of the Michigan Union, which was being used as barracks for the “Student Army Training Corps” led by a Professor Hobbs. “So we began writing the Hobby Horse,” John wrote. “Again, more shrieks – and more circulation.”

And with that the Gargoyle was off and running, printing nine issues a year in the 1920s behind the creative juices of George Lichty, AB ’29, later creator of the long-running “Grin and Bear It” comic strip; and Fred Ziv, JD ’28, who went on to write the TV series “The Cisco Kid” and “Sea Hunt.”

Going dark

Progressive Party presidential candidate Henry Wallace reading the March 1947 issue. Wallace served as U.S. vice president under FDR from 1941-45. (Photo: Bill Hampton, courtesy of U-M’s Bentley Historical Library.)

The Great Depression and the specter of war wreaked havoc on the Garg’sfinances in the 1930s. But one highlight was a 1938 entry penned by novice playwright Arthur Miller, BA ’38, titled, “You Simply Must Go to College,” in which he revealed an early penchant for snide humor.

After the bombing of Pearl Harbor and the U.S. entry into World War II, the magazine’s youthful flippancy seemed unsavory. So for the first time in its short history, the staff ceased publication in 1944. But a year later, with the war over and the GI Bill crowding campus with an abundance of older, wiser (and possibly more cynical) veterans, the Gargoyle rose from the ashes.

Not surprisingly, the writers mined editorial gold from the sexual dynamics between the battle-hardened men who had been off at war for three years and their female counterparts who had missed their presence on campus. One tame example: “A sailor and his girl were riding out in the country on horseback. As they stopped for a rest, the two horses rubbed necks affectionately. ‘Ah me,’ said the sailor, ‘that’s what I’d like to do.’ ‘Well, go ahead,’ answered the girl. ‘It’s your horse.’”

The administration took issue with the magazine’s penchant for raunchy humor and the editors were called in front of the Board in Control of Student Publications. The charge? Running a “venal, sophomoric, salacious, lustful, licentious, and libidinous and thinly disguised mud-raking and pornographic rag without any redeeming literary content.”

Luckily for the Garg,founder White was a member of the board and successfully defended the magazine.

But White could not save the Gargoyle from being kicked off campus after its April 1950 issue, “The Smooth Gargoyle.” Among its offerings was an article, “I Kept a Mistress on the GI Bill,” and an ad for a one-cup bra deemed “vile” by the administration.

He who laughs last

Not to be deterred, the magazine kept publishing from the basement of an off-campus bookstore for two years before being allowed back on campus. The staff stayed mostly out of trouble until the end of the decade, when, in the 1959-60 school year the Gargfeatured a photo of the University president’s house. One of the artists had penciled in a topless woman leaning out of an upstairs window.

“The board didn’t think this was funny,” says 1964 Gargoyle editor and historian John Dobbertin, AB ’64. (Dobbertin obviously thought it was, based on his chuckles some 60 years later.)

Funny money

Whether it was the topless woman or lack of student interest, the Gargoylehad disappeared by fall 1960 when Dobbertin arrived on campus. A professor asked if he would be interested in reviving the magazine. He agreed, and the professor gave him the names of a few past editors to pick their brains.

One, Gurney Williams, a Gargoyle editor in the 1930s and humor editor at Lookmagazine at the time, advised Dobbertin on the tough balancing act he soon would be performing: “If you run a touchy wheeze for the sake of circulation, the faculty raises hell. If you keep it clean, your prospective customers suddenly show more interest in the Congressional Record.”

Running Gargoyle “taught me entrepreneurship,” Dobbertin says. “When I took over we had two file cabinets, a long table, one desk, one typewriter. ‘Be funny kid.’ So I had to take it from there to make it into something students would appreciate and find funny, something they’d plunk down a quarter for.”

“Delicious stuff”

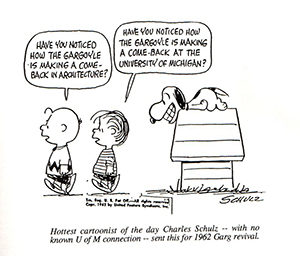

To stay in the good graces of the board and the University administration, Dobbertin kept the magazine on the “clean” side of things. In 1962, he went so far as to request a cartoon from Peanuts creator Charles M. Schulz, and was shocked when the artist actually complied.

‘Peanuts’ creator Charles M. Schulz submitted this cartoon in 1962 upon Dobbertin’s request. (Image courtesy of Gargoyle Laughs at the 20th Century.)

But staying squeaky clean in the turbulent ’60s wasn’t easy. In the early part of the decade, the University decided to turn two dorms into co-ed housing: “Delicious stuff,” Dobbertin says. The May 1963 Gargoyle cover featured men on one side of a dorm jackhammering, drilling and ramming the walls to break into the female side. And while the issue “did not distinguish us as great humorists, it hit the mark with the student body,” he says. “We couldn’t take the quarters fast enough.”

Eventually, the Vietnam War protests reached campus and delivered the edge the magazine needed. Instead of the usual “fraternity humor” that kept the magazine feeling local, the Gargwriters and artists expanded their coverage to national and political events.

“The Gargoyle really didn’t hit its stride until it became firmly anti-establishment against the Vietnam War,” Dobbertin says. “In my opinion, those mid-to-late-’60s Gargswere the best ever produced.”

Nothing captured the campus war debate and Gargoyle’s take on it better than the “Kill-a-Commie-for-Christ Man” cartoon by artist Phil Zaret, AB ’68/MSW ’71. (So much for Charlie Brown.) In today’s parlance, the cartoon “went viral” appearing in publications on campuses around the country. “He just absolutely nailed it,” Dobbertin says.

Despite the rich potential for smart editorial commentary — the lingering war, the tragedy at Kent State, the Watergate scandal, gasoline shortages, and the Iran hostage crisis to name a few — it appeared the student body’s funny bone had gone on hiatus. Regrettably, the Gargwent dark on and off throughout the ’70s.

Back on (the laugh) track

The Reagan years — with “the illusion of prosperity, the promise of post-graduation employment, plenty of beer and pot, and relatively few political protests to interfere with the sale of Gargoyles on the Diag,” as 1981-82 editor Bill Smith later wrote — saw the return of the magazine to campus.

It has been publishing, with an occasional blip, ever since. Wambaugh became editor in 1999 after one of those “blips,” which included the forced resignation of the previous editor, Tony Zaret, who’d followed in father Phil’s Garg footsteps. The board demanded that Zaret turn a profit with the magazine. He responded with a comedic visual presentation that placed the board in the “Realm of Fantasy,” complete with unicorns, fairies, goblins, and elves. (“Alas, the board didn’t look too kindly on my bemused disregard for matters financial,” Zaret wrote later.)

Wambaugh says his memories of college are intertwined with those of working at the Gargoyle. There was something meaningful in carrying on the tradition in the same offices that hosted so many other smart, hilarious people.

“It’s that feeling that snarky people had been in that room forever and probably left hamburger wrappers under one cushion and a gem of a cartoon under another,” Wambaugh says. “You felt connected to the past and also to all the other people. It was a special feeling.”

W.A.P. John - 1974

Once my grandfather sold out all of the advertising space in the standard issue, he worked out a split with the university for additional pages he could sell. He would add an 8 page signatures at the bindery. With the money earned, he was one of the few with a car on campus…

Reply

John Goodreau - 1966

The Gargoyle, I believe, in the the mid 50’s, published a ditty about “Buckeye Delusions”. Need some help to complete.

“This old earth has given birth to some grand and glorious delusions. But none so vain or more insane, than grandiose buckeye delusion. I speak of a region where madmen are legion and mother’s inform on their sons.

Someone help me.

Reply