An ascendant time for cinema

(Image: aafilmfest.org.)

As 1970 dawned in Ann Arbor, the prestigious Cinema Guild was entering its third decade. This vibrant student-run society celebrated film history, past and present, at home and abroad. The guild screened films in Lorch Hall’s architecture auditorium, and I arrived at the University in 1967 just as a full D.W. Griffith retrospective was getting underway. I’ve held onto the guild’s extensive and superb programming notes from that event; they highlight each of Griffith’s films, from the early one-reelers to the historical epics.

During this same period, the Ann Arbor 16mm Film Festival also was thriving. Founded in 1963 by art professor and independent filmmaker George Manupelli, the festival offered an important screen outlet for films that defied mainstream commercial and artistic traditions. Independent filmmakers at this time were experimenting with abstraction, subjectivity, “pure-cinema” impulses, and taboo content as they forced audiences to consider cinematic art in a new way. Staged annually in Lorch Hall, the Ann Arbor 16mm Film Festival drew robust, enthusiastic audiences, including well-known filmmakers and critics. In fact, legendary critic Pauline Kael served as a judge in 1964. Andy Warhol showed up in 1966, bringing with him works by some of New York’s indie darlings.

As the ’70s took hold, Michigan students, much like college students everywhere, were embracing motion pictures as a central element in the abrupt cultural transformations taking place in the country. Just three years earlier, director Mike Nichols had zeroed in on youth malaise and alienation in an affluent American family with The Graduate (1967). The innovative script’s bold dialogue and sexual expression played out to an album-length set of plaintive pop songs by Simon and Garfunkel.

Two years later Easy Rider (1969) and Five Easy Pieces (1970) delivered film narratives starring anti-heroic drifters, uncommitted beyond a search for self-liberation. As nonchalant Bobby Dupea in Five Easy Pieces, Jack Nicholson says, “I move around a lot — not because I’m looking for anything really, but I’m getting away from things that get bad if I stay.” Many young filmgoers saw themselves reflected on the screen, a generation roiling in restless crisis.

Hollywood comes to campus

The University’s reputation as a savvy center for film culture resonated with several important Hollywood figures, many of whom were honored with retrospectives. The visits always included informal classroom tete-a-tetes. Those of us lucky enough to have been a part of the campus visits were able to experience a large swath of American motion-picture history in remarkably personal and memorable ways.

The auteurs

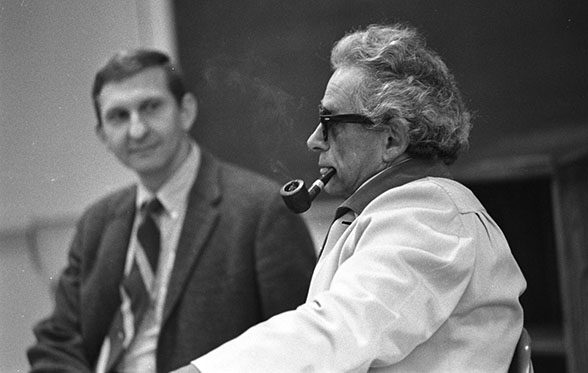

Samuel Fuller (1912-97)

Noted and revered B-picture director Samuel Fuller came to campus in early February 1970 for the third Director’s Festival co-sponsored by the Cinema Guild and the local Creative Arts Festival. Fuller was known for his low-budget genre pictures: westerns (I Shot Jesse James, 1949); war films (Fixed Bayonets, 1951); spy thrillers (Pickup on South Street, 1953); and film noir (Underworld USA, 1961). In anticipation of Fuller’s visit, The Michigan Daily reported, “The odds are that you’ve seen at least one Fuller film and the odds are that you don’t remember it.”

Fuller was scheduled to screen and discuss the thriller Pickup on South Street. As an amusing side note, that week I received a phone call from a University official asking if the film’s content was decent (or something to that effect). The call obviously was prompted by the legal entanglement that ensued after the Cinema Guild’s attempt in 1967 to screen Jack Smith’s Flaming Creatures (1963). That film was a cinematic romp with gender-ambiguous figures and a staged orgy. The police halted the screening midway through and confiscated the print. Four members of the Cinema Guild (three students and a professor) faced charges of screening a pornographic film. (See: “The Flap Over Flaming Creatures,” Michigan Today, April 14, 2010).

Fuller’s presentation was less eventful, but equally exciting. When he visited my Film Theory class in the Frieze Building, he demonstrated one way in which he created spontaneity on set. He described a hypothetical situation in which characters are engaged in an animated conversation, smoking cigarettes in a living room. During rehearsal, Fuller would surreptitiously move a pack of cigarettes and two ashtrays to new locations, thereby forcing spontaneous “responses” from his actors.

Made a decade after his campus visit, Fuller’s autobiographically inspired war picture, The Big Red One (1980) with Lee Marvin and Mark Hamill, earned critical praise as one of the greatest war movies of all time.

Frank Capra (1897-1991)

After my recent article about holiday-centric films, including It’s a Wonderful Life (1946), former student Don Sowle recalled a 1973 class visit from director Frank Capra. Capra was retired at the time, having ended his career with A Pocketful of Miracles (1961). The picture was a remake of his first big-screen success, Lady for a Day (1933).

Although It’s a Wonderful Life wasn’t yet the sensation it eventually would become, Capra described it as an ideal realization of his long-standing desire to celebrate the “little man” who rebounds from self-doubt, emerges as a survivor, and sees his faith restored. For those reasons Capra cited It’s a Wonderful Life as the one film that pleased him most.

The director also expressed his professional determination to maintain creative command of his film projects without front-office interference or committee-regulated production strategies. That said, Capra enjoyed collaboration. He spoke fondly to students of his significant long-term professional relationship with Robert Riskin, a New York playwright-turned-screenwriter. Riskin had written Capra’s Lady for a Day and the two multi-Oscar nominated classics, It Happened One Night (1934) and You Can’t Take it With You (1938).

Speaking of writing, Capra had just published his autobiography, The Name Above the Title (MacMillan, 1971), and he carried the hefty book around the U-M campus like a proud father.

(Note of historical interest: Sam Fuller and Frank Capra’s time spent on campus sharing their work and personal commentaries on film art affirmed the newly emerging theory of the “auteur” director — in a nutshell one who “authors” a film through a driving personality and individual artistic control of the filmmaking process).

The technician/artists

Two remarkable technician/artists, Linwood Dunn and Karl Struss, also visited campus in the 1970s.

Linwood Dunn (1904-98)

Many film historians consider Dunn to be the greatest special-effects artist and camera innovator in the pre-digital filmmaking era.

Effects wizard Linwood Dunn used camera tricks to put “Baby,” the leopard, in a scene with human actors.

Dunn worked at RKO Radio Pictures for three decades. He was a master in the art of motion picture compositing that combined rear-screen projection and foreground live action. He did this with the aid of an optical printer — to bring the separate images onto a single film mise-en-scène. In 1933, Dunn joined Willis O’Brien’s effects team to create RKO’s King Kong. The camera captured four miniature armature models of Kong, between 18-24 inches tall, in a stop-motion, frame-by-frame process. The footage was composited before live-action background projections. The on-screen imagery gave Kong the presence of a gigantic 18-foot monster, albeit an empathetic one.

Dunn enthralled me and my students with his insider view of cinematic “trickery” used in some of Hollywood’s most beloved films, many of which were classic choices for Cinema Guild screenings. The ever-popular Bringing up Baby (1938) is a good example. In that RKO romantic comedy, rear-screen projections and pictorial compositing facilitated much of the slapstick interaction between the pet leopard, “Baby,” and its costars Katharine Hepburn and Cary Grant.

Dunn also experimented with matte-screen compositing in Citizen Kane (1941). In this process, an area of the screen action is partially blocked, leaving an “unexposed” black area into which a separate action can later be optically composited. This gives the impression of an organic, singular image. Notably, this process occurs in Citizen Kane when politician James W. Gettys (Ray Collins) observes his opponent Charles Foster Kane (Orson Welles) delivering a campaign speech in an auditorium. Gettys, in a surprise close shot, appears to be standing at the edge of an upper balcony box, far removed from the platform stage below. The effect of the matte-shot suggests a sinister moment of political stalking.

In 1946, to meet the burgeoning demand for his services, Dunn founded the Film Effects of Hollywood company. During his visit to Ann Arbor, he presented U-M students with film clips and slides from his personal visual effects collection that highlighted later work. One presentation included the 1960s films Hawaii (1966) and It’s a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World (1963).

The epic Hawaii, shot in wide-screen Panavision for projection onto a huge theater screen, was breathtaking in its display of the island’s magnificent beauty and its often-tempestuous weather.

Stanley Kramer’s It’s a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World, filmed in Ultra Panavision 70, featured a large set of characters in a zany rush to locate a cache of buried money in California. Ultra Panavision 70 employed a single projector for an extreme wide-screen vista. Dunn’s contribution to the film included visual compositing of as many as two dozen separate color elements into the frame imagery. Later special-effects work included an entree into television, most notably for Desilu Productions and the “Star Trek” TV series.

In 2003, to honor his singular place in motion picture history, the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences opened the Linwood Dunn Theater in Los Angeles as a state-of-the-art screening facility for academy events. Dunn’s personal collection of visual-effects materials is archived there.

Karl Struss (1886-1981)

When Karl Struss visited campus in February 1976, cinephiles were anxious to explore his media background, which held both historical and artistic significance. A renowned cinematographer, Struss also played a significant role in the “Photo-Secession” movement founded in 1902 by Alfred Stieglitz and F. Holland Day. As Stieglitz defined the movement in the photo journal Camera Work: “Photo-secession actually means a seceding from the accepted idea of what constitutes a photograph — the manipulation of photographic images by the photographer to achieve subjective vision, to be judged on its merits as a work of art independently without consideration that it had been produced through the medium of the camera.”

Before turning to cinematography, Struss had developed a reputation as a still photographer who favored platinum prints on paper and soft-focus imagery abetted by his own invention — the Struss Pictorial (“soft focus”) Lens. In 1910, Stieglitz selected a dozen of Struss’ photographs for the International Exhibition of Pictorial Photography at the Albright-Knox Art Gallery in Buffalo, N.Y.

Appropriately for the occasion of Struss’ visit to Ann Arbor, the U-M Museum of Art hosted the exhibition “Karl Struss: Man with a Camera.” Struss experts John Harvith and Susan Edwards Harvith, ’73, assembled the show, which premiered at Detroit’s Cranbook Academy Museum of Art and opened in Ann Arbor on Feb. 25, 1976. The headline on Jane Siegel’s review in The Michigan Daily read: “Struss Exhibit Recalls a Photographic Genius” (Feb. 24, 1976).

When Struss embraced filmmaking in the early 20th century, he took with him his “soft focus” approach to pictorial imagery. He employed the technique mostly in motion picture publicity stills and posters. The revolving refinement of the technique in screen cinematography would earn Struss (with Charles Rosher) the first Oscar for Best Cinematography in 1929 for F. W. Murnau’s highly stylized, altogether expressionistic film Sunrise: A Song of Two Humans (1927). With its glittering moonlight and reflective water, its forced-perspective cityscapes, and its fantasized iteration of an amusement park, Struss’ camera imbued the triangular love story with an aura of sensory delight and allegorical meaning. It’s often cited as one of the great films of all time.

Watching Sunrise in Lorch Hall with Struss present was indeed special. This month the British Film Institute is screening the film with an introduction about its place in film history by director Hugh Hudson (Chariots of Fire). I’ll be there.

Other iconic cinematographic achievements by Struss include Charles Chaplin’s The Great Dictator (1940) and Limelight (1952), and Journey into Fear (1942), Mercury Theater’s production starring Orson Welles and Joseph Cotton.

Struss was a founding member of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. Like Dunn, he worked in television in later life (“Broken Arrow,” “My Friend Flicka”) until retiring at age 86.

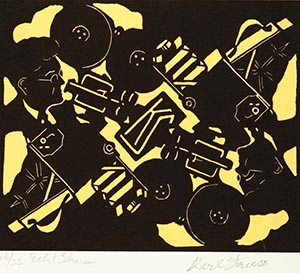

When the filmmaker visited Ann Arbor, his wife of 55 years Ethel (nee Wall), accompanied him. Ethel was a warm and vital partner whom Struss described as a sort of “muse” during his long and varied career. Often she posed as a model for his secessionist “pictorial-art” photographs. After their return to L.A., Ethel Struss remembered me with a signed drawing she had made of her husband titled “Karl Struss With Bell & Howell Motion-Picture Camera.” The drawing also was sent to the U-M Museum of Art and is archived there.

Having Sam Fuller, Frank Capra, Linwood Dunn, and Karl Struss visit campus demonstrated the significant role that U-M and Ann Arbor played in providing a venue for film lovers, film students, and filmmakers. That role continues to this day: The 56th Annual Ann Arbor Film Festival runs March 20-25 at the Michigan Theater.

Robert Crockett - 1973

Professor Beaver,

I enjoyed your “Michigan Today” article about Frank Capra and other film artists visiting campus in the 1970s. I graduated from the University in 1973 and was a student in the class that Frank Capra visited. Since you say Capra was on campus in 1973 and I graduated that spring, the class must have been in my final semester.

Many of his films were screened on campus during the week or so before his visit, and I attended most if not all of them, and I read his book. The instructor, whose name I can’t recall now but who was a terrific teacher, asked each of us — there were perhaps 25-30 students in the class — to think of a question we could ask Capra when he was in our class. I asked him whether, when he made the “Why We Fight” films for the government during World War II, the government ever asked him to change anything. He said that only happened once, when he was asked to remove a brief sequence showing Franco shaking hands with Hitler, because the U.S. administration was hoping to improve relations with Spain and didn’t want to antagonize Franco.

Thanks for your article.

Reply