Beyond the greasepaint

The larger importance of and curiosities surrounding that singular, idolized comedy troupe the Marx Brothers is an ongoing story of assessment and reassessment.

It was 1969 when I first became aware of the Marx Brothers as a comedic force whose zany antics and nihilistic approach to language as communication had not only titillated vaudeville, theater, and film fans but had also resonated with visionaries who were developing revolutionary ideas about the possibilities of dramatic expression.

Theatrical influences

Those of us graduate students in Professor James Coakley’s “Modern Theater” class were introduced to the theoretical writings of French poet/dramatist Atonin Artaud (1896-1948). Artaud had become a leading figure in the 20th-century European avant-garde movements that were stylistically designated Theatre of Cruelty and Theatre of the Absurd.

Those of us graduate students in Professor James Coakley’s “Modern Theater” class were introduced to the theoretical writings of French poet/dramatist Atonin Artaud (1896-1948). Artaud had become a leading figure in the 20th-century European avant-garde movements that were stylistically designated Theatre of Cruelty and Theatre of the Absurd.

In 1931 Artaud wrote an inspired essay on the Marx Brothers’ unique modus operandi after seeing Animal Crackers (1930). Later expanded and published in the essay collection The Theatre and Its Double (1938) Artaud wrote:

“…in Animal Crackers each character was losing force from the very beginning. Here for three-quarters of the picture one is watching the antics of clowns who are amusing themselves and making jokes, some very successful, and it is only at the end that things grow complicated, that objects, animals, sounds, master and servants, hosts and guests, everything goes mad, runs wild, and revolts amidst the simultaneously ecstatic and lucid comments of one of the Marx Brothers…There is nothing at once so hallucinatory and so terrible as this type of manhunt, this battle of rivals, this chase in the shadows of a cow barn, a stable draped in cobwebs, while men, women, and animals break their bounds and land in a heap of crazy objects, each of whose ‘movement’ or ‘noise’ functions in its turn.”

From animals to opera

This pointed appraisal of the Marx Brothers’ unconventional comic mayhem in Animal Crackers might fit as well for a review of my favorite of their films, A Night at the Opera (1935). Here are some comparable elements: the film’s wild, destructive mayhem of operatic performance — the most reverential form of musical theater; the mockery of language in the contract-reading scene with Driftwood (Groucho) and Fiorello (Chico), as Chico responds to the contract’s mental health clause — “Ha ha ha ha ha! You can’t fool me. There ain’t no Sanity Clause!”; the cramming of 15 ship passengers into a tiny stateroom; Driftwood, Fiorello, and Tomasso huddling with waiters bearing trays of food; a maid with a mop and bucket and Groucho stating: “You’ll have to start with the ceiling.”

This pointed appraisal of the Marx Brothers’ unconventional comic mayhem in Animal Crackers might fit as well for a review of my favorite of their films, A Night at the Opera (1935). Here are some comparable elements: the film’s wild, destructive mayhem of operatic performance — the most reverential form of musical theater; the mockery of language in the contract-reading scene with Driftwood (Groucho) and Fiorello (Chico), as Chico responds to the contract’s mental health clause — “Ha ha ha ha ha! You can’t fool me. There ain’t no Sanity Clause!”; the cramming of 15 ship passengers into a tiny stateroom; Driftwood, Fiorello, and Tomasso huddling with waiters bearing trays of food; a maid with a mop and bucket and Groucho stating: “You’ll have to start with the ceiling.”

In his pivotal book The Theatre of the Absurd (1962) Martin Esslin wrote:

“With the speed of their reactions, their speed as musical clowns, and the wild surrealism of their dialogue, the Marx Brothers clearly bridge the transition between the commedia dell’arte and vaudeville, on the one hand, and the Theatre of the Absurd on the other. A scene like the one in A Night at the Opera in which more and more people stream into a tiny cabin on an ocean liner has all the proliferation and frenzy of Ionesco.” (Here Esslin was alluding to the proliferation of objects in stage plays by Ionesco, e.g., 1952’s The Chairs.)

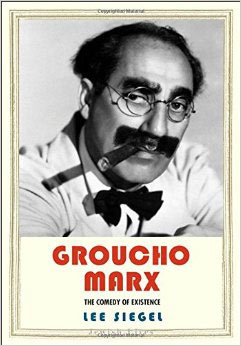

Groucho Marx: The Comedy of Existence

Now the fascination with the Marx Brothers has taken yet another tack in Lee Siegel’s Groucho Marx: The Comedy of Existence,published in January as part of Yale University Press’ Jewish Lives series.

Now the fascination with the Marx Brothers has taken yet another tack in Lee Siegel’s Groucho Marx: The Comedy of Existence,published in January as part of Yale University Press’ Jewish Lives series.

Siegel’s book is a brief one, 144 pages plus endnotes, but it’s a work with depth and originality as he builds a psychoanalytic, philosophical thesis about the unextractable part played by the Marx Brothers’ own lives in their comedy. Siegel calls his study a “bio-commentary,” one “that weaves the outward facts of Groucho’s life into and through a story about the inward facts of Groucho’s life.”

Extending his thematic arguments to include the other Marx Brothers as well, Siegel writes: “What I want to try to show is the extent the Marx Brothers, every bit as Oscar Wilde did on a different level, dissolved the boundary between life and art, public and private.”

Beginnings

The third surviving son of Minnie and Simon (“Frenchie”) Marx, immigrants to America from Germany and Alsace-Lorraine respectively, Julius Henry Marx (Groucho) was born in 1890 in the immigrant-populated Manhattan community of Yorkville. He was raised in a house on the city’s Upper East side, a house that teemed with visiting relatives and drop-in neighbors, not to mention minimal living arrangements for the five Marx boys.

Siegel contends the conditions of Julius’ childhood in Yorkville turned him into “the unassuming and seemingly unremarkable middle child…largely lost in the familial tumult, unseen and unheard.” Any larger ambitions Julius might have had were quickly extinguished (the desire to be a doctor for one) when mother Minnie, often a berating presence in her son’s life, forced him to drop out of school at age 13 to work in a wig factory. With a fine singing voice and a flair for comic impersonation, Julius at age 15 won a spot in the Leroy Trio, a touring vaudeville act that helped him escape from the wig factory.

Siegel writes that Julius’ sense of himself as an overlooked child would lead him, as an adult performer, to the persona known as Groucho: “a man speaking as though he never expected to be heard.” Perhaps that accounts, Siegel says, “for all those uncanny moments in the Marx Brothers’ films when Groucho is outrageously insulting someone, usually Margaret Dumont, who nevertheless continues to talk to him as though nothing untoward, let alone aberrant, was happening.”“You’re one of the most beautiful women I’ve ever seen,” Groucho tells Dumont in The Cocoanuts (1929). “And that’s not saying much for you.”

Groucho also learned to get laughs with his flirting, fluttering eyelids and the lifting of his bushy eyebrows. Siegel sees Groucho’s demeanor this way: “The glasses bespoke a cerebral figure; the mobile eyebrows insinuated that behind the glasses was a man who took nothing seriously; the greasepaint mustache proved that all appearances, social and personal, are either suspect or arbitrary or both. Words and images echo each other constantly in the work of the Marx Brothers…”

Visual imagery and words coalesce in this exchange in Animal Crackers:

Mrs. Rittenhouse: “Captain Spaulding, you stand before me as one of the bravest men of all times.”

Spaulding: “All right, I’ll do that.”

Verbal doggerel

In a very amusing and informative chapter titled “Interlude: Words,” Siegel offers an account of the comic skit standard “doggerel,” used by the Marx Brothers in their early careers as vaudeville performers. Doggerel, where a poem’s words and rhythms are altered to lose their understood meanings, was part of their hugely successful routines and labeled “Peasie Weasies” by the brothers. Siegel gives several examples including this one:

“A humpback went to see a football game.

The game was called on account of rain.

The humpback asked the halfback for his quarter back.

And the fullback kicked the hump off the humpback’s back.”

Verbal doggerel was notable in varying degrees in all of the Marx Bothers films, classically illustrated in the lengthy contract reading scene between Groucho and Chico in A Night at the Opera.

Returning to his central theme Siegel says: “Within this new verbal world words become reconstituted as free autonomous entities, no longer bound to social meaning. The new, reconstituted words throw open new horizons of meanings, a revelation not lost on three men who were once poor and oppressed by seemingly immovable social givens.”

Revealing sideline commentaries

Groucho Marx: The Comedy of Existence,unfolds through a variety of fascinating sideline commentaries that contribute to the overall story being told:

Groucho Marx: The Comedy of Existence,unfolds through a variety of fascinating sideline commentaries that contribute to the overall story being told:

- The feisty relationship between Groucho and T.S. Eliot.

- Commentary on the narrative effect that a weak father had on the treatment of authority figures in the Marx Brothers’ films.

- The Marx Brothers’ comedy — especially language and jokes — vis a vis traditional/classic Jewish humor.

- The circumstances and psychological implications of Groucho’s most iconic line: “Please accept my resignation. I don’t want to be in a club that will accept me as a member.”

- Analytical explanation for the successful transition of the Marx Brothers from vaudeville to silent films to talkies.

- An ongoing comparison of the Marx Brothers’ comedy with classic performers (Charlie Chaplin, Buster Keaton, W.C.Fields, Lenny Bruce, Henny Youngman) and contemporary comedians (Woody Allen, Bill Maher, Sasha Baron-Cohen, Louis C.K.).

- The efforts of producer Irving Thalberg of MGM to tone down the misogynistic treatment of women that had been prevalent in the Marx Brothers’ Paramount-produced films.

- Treatment of the moral and social implications of satire in the films Monkey Business and A Day at the Races.

- Groucho, in his final performance years, as the caustic host of the television show “You Bet Your Life” (1950-61).

Siegel’s book is a provocative one whose thematic points may at times appear a bit over-worked, but it’s a very readable, engaging, and worthy new entry in the rather sizable world of Marx Brothers scholarship.

As Siegel notes in his concluding “Sources,” most of the biographical writers tackling Groucho Marx “rarely get beyond extended celebrations of the ‘beloved’ comic. The greasepaint — not to mention the fake eyebrows and mustache — almost never comes off.”

As the author of Groucho Marx: The Comedy of Existence, maybe that’s a self-rendered pat on the back, but it’s not one without justification.

Donna Ponte - 1972

Such intelligent humor. Never thought of the Theatre of the Absurd connection. (I was a French major.) Sounds like a great read.

Reply

Gordie Connelly - 94

It is always stimulating to read Dr Beaver’s articles it brings back classroom memories it why we all look at film in different way. Thank you Frank

Reply

Rob Fagerlund - 1988

The humpback doggerel is a verse from the old country song, “The Same Old Tale That the Crow Told Me,” by Johnny Horton.

Reply

Harry Epstein - 1971 and again in 1972

Loved your perspective(s) on Groucho and his gang. Chico’s mom helped me find Peerce as a stage name ! ! !

Reply