Unfinished business

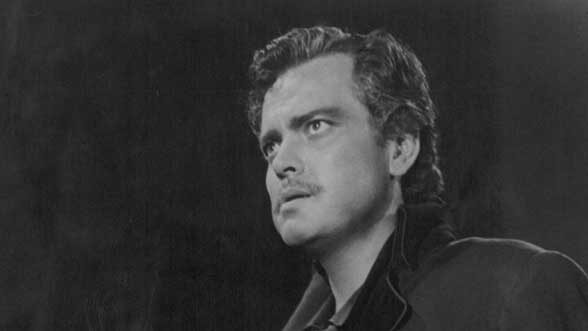

Welles performs a levitation trick in an image that appeared on the cover of Paris Vogue (1982/1983). (Image courtesy of U-M’s Special Collections Library.)

Though he is considered by many as one of the world’s greatest filmmakers, Orson Welles was an actor, producer, writer, and radio broadcaster. He also was notorious for leaving many of his projects unfinished.

Perhaps that is what makes the Welles collections at the University of Michigan so intriguing.

“Not a week goes by that somebody from somewhere in the world doesn’t inquire about something in these archives,” says Philip Hallman, curator of U-M’s Screen Arts Mavericks and Makers collection. “The reality is, there’s a lot yet to be discovered, which is why we’re excited to be adding more to our already extensive Welles holdings.”

Archivists at U-M have started to process eight boxes of materials that recently arrived from Oja Kodar’s home in Croatia. Kodar is a Croatian actress, screenwriter, and director — and Welles’ partner during the final 24 years of his life.

Hallman confirmed that this particular acquisition stands out because the contents are “much more personal” than the other five U-M Welles collections.

Hidden treasures

The boxes contain a number of unpublished photographs, notes between Welles and his first wife, letters from fellow Hollywood directors, and scripts containing magic trick patter for television shows Welles frequented.

It’s possible, however, that the most important finding within the incoming collection includes portions of a very raw draft of his incomplete, unpublished personal memoir, tentatively titled Confessions of a One-Man Band.

The draft, written on a typewriter and containing handwritten notes and edits throughout, includes passages about Welles’ mother and father; his second wife, actress Rita Hayworth; his friend, writer Ernest Hemingway; and director D.W. Griffith — to name a few.

“If you think of it as puzzle, this is another important piece that brings us closer to being able to see the bigger picture,” Hallman says. “Having an opportunity to look at [Welles] as a father, as a husband, as a friend — you get to see what was happening behind the scenes, including the struggles and the missed opportunities and the agony that he was experiencing.”

Inside the mind of an auteur

Hallman, who is still reviewing parts of the memoir that are interlaced throughout the boxes of materials, says a published autobiography probably won’t happen anytime soon.

“It doesn’t appear to be anywhere near a final draft, but that doesn’t mean it won’t be important for scholars or researchers,” he says. “There’s a lot of evidence we’ve found that explains why he didn’t — or couldn’t — finish some of his projects.”

Kathleen Dow, head archivist at the special collections library, anticipates that the recent acquisition will take nearly five months to process before it is available to the public.

Since 2015 marks what would have been the year of Welles’ 100th birthday, Dow says this year has been particularly busy.

Recent developments and research:

- U-M alumnus Brad Schwartz published a book based on a discovery that he made about Welles’s famous 1937 “War of the Worlds” broadcast while Schwartz was completing his undergraduate degree at U-M just a couple of years ago. A book based on this discovery, BROADCAST HYSTERIA: Orson Welles’ War of the Worlds and the Art of Fake News, was published earlier this month.

- Producers who recently kicked off a crowdfunding campaign to raise $2 million to “complete” one of his unfinished films — The Other Side of the Wind — have visited U-M’s collections to review the original script and to research other aspects of the film.

- U-M’s Screen Arts and Cultures program offered a class, taught by associate professor Matthew Solomon, on Orson Welles earlier this year. The semester culminated in an exhibition at the U-M Hatcher Graduate Library.