Update: The same week this story was posted, Nebraska announced it would be joining the Big Ten. Other schools are expected to follow, while at the same time other conferences look to expand as well. In the midst of this upheaval, U-M’s experience leaving and returning to the Big Ten contains lessons for the future.

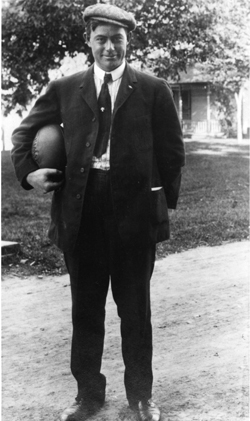

Fielding Yost led U-M’s 1907 walk-out of the Big Ten. U-M came back, but not before finding its most important rivals elsewhere. (Photo: U-M Bentley Historical Library.)

In the beginning

Stability was the rule in the Big Ten from the time it added Michigan State in 1950 to Penn State’s inclusion 40 years later. But in the league’s 115-year history, that long period of calm was its only one. In five of the league’s first seven decades, at least one school hopped on or jumped off. A bigger surprise: The only school to leave and return to the conference is the school perhaps most identified with the Big Ten itself: the University of Michigan. The ripples from those tumultuous transitions a century ago are still felt throughout college football today. In 1901, Michigan brought Fielding Yost to Ann Arbor for a purpose: to win games, win Big Ten titles, and beat mighty arch-rival Chicago. Heading into the last game of 1905, Yost had achieved all that and more. He’d won 55 games—against only one tie—four straight Big Ten titles, and his first four games against Chicago, by a 93-10 margin.

Only after it quit the Big Ten did Michigan develop fierce rivalries with Ohio State, MSU and Notre Dame.

But when he arrived in Ann Arbor, Yost had even bigger ambitions. He was determined to get some respect from the Eastern establishment—and he did. Before the days of polls, writers usually settled informally on one or two teams as the best in the nation. During Yost’s Point-A-Minute years, they tabbed Harvard and Michigan in 1901, Princeton and Michigan in 1902, Yale and Michigan in 1903 and Penn and Michigan in 1904. The Eastern representative always changed, but Michigan consistently stood as “Champions of the West”—on a par with its Eastern brethren.Throughout the 1905 season, it looked like nothing could stop Yost’s juggernaut from stretching its string of unbeaten seasons, Big Ten titles and national crowns—but that’s when things got interesting. The University of Chicago’s legendary coach, Amos Alonzo Stagg, had been king of the nascent Big Ten until Yost showed up—and Stagg resented losing the throne. Watching Yost become the first “Western” coach to win a national title, while drubbing Stagg’s Maroons each year, could not have helped. In the 1905 season’s last game, many believe Stagg sent one of his lesser players in to get one of Yost’s stars kicked out of the game—and it worked, helping Chicago win by the meager margin of 2-0. Stagg’s razor-thin victory protected him from being accused of sour grapes, and freed him to make every effort to get Yost kicked out of the league. But instead of a frontal assault, Stagg squeezed Yost out by promoting a series of reforms he hoped Yost wouldn’t accept. Stagg’s timing was perfect. In 1905 alone, 18 players died on college football fields. The man in the White House, President Theodore Roosevelt, was a fan of the game, but for that reason he called the coaches and presidents of Harvard, Yale and Princeton together to urge reforms. This meeting begat another meeting, which gave birth to the Intercollegiate Athletic Association. Five years later, in 1910, the IAA renamed itself the NCAA, and an institution was born. Reform was all the rage in college football—and that’s where Stagg saw his chance. As the de facto leader of the Big Ten, Stagg pushed for new rules governing recruiting, funding and eligibility—which Yost, probably to Stagg’s surprise, readily agreed to—but Yost couldn’t stomach the conference’s proposals to reduce schedules from a robust eleven games to a measly five, restrict player eligibility to three years, and insist that football coaches be full-time faculty members. Stagg already was, Yost was not. Yost knew if he complied with the new Big Ten regulations, his team would have little chance against the Eastern powers. To sacrifice that hard-won recognition galled Yost.

Adding insult to injury, Stagg joined forces with U-M’s own President James B. Angell, who might have been Yost’s second-biggest enemy. President Angell simply hoped to return college athletics to the English ideal of mens sana in corpore sano—”sound mind in sound body”—which emphasized more student participation and less notoriety for the victors.

Stagg’s motives were less altruistic. Though Stagg wasn’t any more pious than Yost, he was willing to accept the changes himself if it meant slowing down Yost’s Point-a-Minute squads. Having finally beaten Yost, he probably wasn’t anxious for a re-match. When it came time for Michigan’s Faculty Board in charge of Intercollegiate Athletics to vote, Yost urged them to refuse the conference proposals. They did, forcing Michigan to drop out of the Big Ten in 1907.That’s right: Michigan, the school most closely associated with Big Ten football, left the conference in a huff.

A team adrift

At first the students and alumni were happy with the decision, until the Big Ten passed a rule prohibiting conference teams from scheduling any more games against former members who had since withdrawn—an edict clearly aimed at ostracizing Michigan, the only team to leave the Big Ten—which they called the “non-intercourse” rule. Yost’s decision to leave the conference had other equally unintended, and equally lasting, side effects. Michigan didn’t play Chicago for another 12 seasons, so it had to resort to filling the schedule with independent schools like Notre Dame twice, and Ohio State, which was not yet in the Big Ten, for the first six of those years. Another independent, the Michigan State Spartans—then called the Michigan Agricultural College Farmers—appeared on Michigan’s schedule for just the third time in 1907, and have continued to do so all but four seasons since. Over time, leaving the Big Ten generated more problems than it solved. Michigan scheduled yearly games against Cornell, Penn and Syracuse, but those rivalries never matched the intensity of the Chicago and Minnesota games. Worse, to fill out its schedule, Michigan had to play teams like Lawrence, Mt. Union and Marietta. And even if Michigan’s football team could survive being outcast by the Big Ten, its other varsity teams could not.

Returning home

In November of 1917, ten years after Michigan told the Big Ten what to do with its new regulations, both sides agreed it was in everyone’s best interest for Michigan to return to the conference. Yost submitted to the Big Ten’s rules, and the conference schools welcomed Michigan back without resentment. The Wolverines’ decade in the wilderness cost them continuity, conference titles, money and national prestige, but ultimately, Yost got almost everything he wanted. In hindsight, being dropped by Chicago was a good deal. Michigan lost a rivalry with a school that was fading fast, and three of Michigan’s non-conference replacements—Ohio State, Michigan State and Notre Dame—remain the Wolverine’s biggest rivals to this day, which helped two of them gain admission to the Big Ten. Since returning to the Big Ten, Michigan has won 36 conference titles and seven national crowns. Stagg’s Chicago teams, which had won five of the first 18 Big Ten titles, won only two more after Michigan returned, finally dropping football altogether in 1939. That made room for Enrico Fermi to create the first controlled nuclear reaction under the empty stands of Chicago’s football stadium. (Fermi, by the way, also lectured at Michigan.)So, whenever a commentator remarks that Michigan is the nation’s only team with three great rivalries, Wolverine fans should thank Amos Alonzo Stagg, who made it all possible—however unwittingly. And whenever someone says they know exactly how the rumored Big Ten expansion will play out, remember that the biggest consequences of that conference shake-up long ago were completely unexpected.

Jim Hallett - 1972

I enjoyed the article and did not realize UM was out of the conference that long. Yes, the new rivalries did help, and U of Chicago is long-forgotten in football, but the proposed expansion of the Big Ten is just whoring for more money. We do need a 12th team – ND, the logical choice wanted no part, so Mizzou or maybe Pitt – would have been OK. I do not want 16 or 18 teams. We’ll be lucky to maintain any rivalries, given the “dumbing down” of our non-conference schedule with 1-AA (FCS) and MAC teams galore, and the fact it will be hard to have any continuity in 8 BT games with 15 or 17 other conference teams. Considering how poorly the football and basketball programs have fared of late, it may not matter anyway!

Reply

Matthew Benz - 1998

Interesting history lesson. Thank you!

Reply

David Wilson - 1971, 1976

Thanks John very interesting.

Reply

Roger Williams - 1985

John,

Interesting story. I’d be interested in reading one slanted toward the interrupted chronology between Michigan and Notre Dame, and the underlying drivers/dynamics.

RW

Reply

Hosting Hosting - 1987

The Official Athletic Site of Michigan Wolverines a Facilities , partner of CBS Sports Digital. Service dogs in training are allowed into Yost Ice Arena only if they are also with the person who will be their owner; however, puppies that are being socialized and have not completed their training as a service animal are not permitted in Yost Ice Arena.

Reply