Emanuel Tanay as a child in Miechow, Poland, with his sister and father. A few years after this photo was taken, Tanay’s father was murdered in a concentration camp. (Photo courtesy Emanuel Tanay.)

Forgotten heroes

The odds say that Emanuel Tanay should not exist. The fact that he now lives in Ann Arbor, retired after a celebrated career as a forensic psychiatrist, is testament to his wit and will, to chance, and to strangers who risked their lives to help him. Without them, he’d have been killed 60 years ago.

He was born Emanuel Tenenwurzel, and he came of age in the inferno of the Holocaust. In 1939, when Nazi Germany invaded his native Poland, he was 11. For years he lived in hiding and on the run, narrowly escaping death several times. His father and many other relatives were killed, but he, his mother and his sister survived.

Today Emanuel Tanay resides in an airy, sunny Ann Arbor home decorated with colorful oil paintings, its many shelves jammed with books about the war. Down one hallway, old photographs hang: here is Tanay as a boy in a sailor suit.

Here he is holding hands with his father, and here he’s on his mother’s lap. But you can’t look at the happy family without thinking of what was about to hit them.Tanay himself is tall and fit-looking, with an arsenal of strong opinions he voices with a Polish accent. Tanay was recently diagnosed with cancer, and though he is being treated for it, at 82 his mortality looms large. It’s a reminder, too, that even the youngest Holocaust survivors are reaching their 80s. The time to gather their memories—the last eyewitness accounts—runs short. Tanay has been working for years to keeping his memories alive. He contributed early to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, DC, and he was interviewed for the museum’s oral history archive. In 2005, he published a memoir, “Passport to Life,” about his wartime experiences. And in 1987, he also gave an interview to an unusual project: the Voice/Vision Holocaust Survivor Oral History Archive.

Voice/Vision

Tanay with his mother. (Photo courtesy Emanuel Tanay.)

Housed at the University of Michigan-Dearborn, the Voice/Vision Archive is the remarkable and oddly personal brainchild of history professor Sidney Bolkosky. Since 1981, Bolkosky, archive curator Jamie Wraight, and other researchers have interviewed at least 200 Holocaust survivors, posting more than half the transcripts and recordings online. Because of Bolkosky’s devotion to the task, UM-Dearborn was among the world’s first institutions to start gathering survivors’ testimony. Voice/Vision is now the world’s most accessible archive of Holocaust accounts.

Better yet, the archive gets used. Wraight says that classrooms from Philadelphia to Washington state make the material part of their curriculum, in some cases even linking middle school students to survivors themselves. “I see our role,” Wraight says, “as outreach, teaching, and guarding these survivors’ memories… Survivors seem to get two things out of it. One is catharsis of a sort—though not a complete one. Sid (Bolkosky) is a very gentle soul; people trust him” with their stories.

Wraight says many survivors have told Bolkosky that their interview with him was the most complete, the most honest accounting they ever gave of their experiences. That’s important both personally and historically, because, notes Wraight, a second benefit of providing an oral history is that “a lot of [survivors] see this as advocacy, fighting Holocaust denial.”

The looming horror

Like many survivors, Tanay insists on telling his story with scrupulous accuracy. The facts are so important. In his home this summer, accompanied by his daughter Elaine (’75, MSW ’77), Tanay recalled that after the German conquest of Poland, genocide arrived slowly.

“I was in fifth grade when public schools were banned,” he says. Then came legal restrictions and Star-of-David armbands. Later Jews were relocated to ghettoes—which were initially just segregated areas of town. But before long the ghettoes were walled off, becoming virtual prisons. That was when the real horrors took hold. “You set one foot outside [the ghetto walls] and you were shot. People were dying of starvation. Bodies all over.”

Periodically the Germans launched mass deportations: “anyone who did not have a job was deported for ‘labor'” (that is, to concentration camps). And yet it remained difficult to believe the evidence of where these policies were heading. “My father had dangerous optimism,” Tanay says. “He believed he had ‘Vitamin P.’ Protection. Friends in high places.” Tanay’s father was a dentist and well off, with connections to wealthy Christians, and his family neither looked nor sounded Jewish at a time when most Polish Jews were poor and orthodox and spoke much better Yiddish than Polish.

On the run

Despite his father’s optimism, Tanay’s mother was terrified. “She wanted me out. She trusted her gut.” She arranged an escape. While she and her daughter found a refuge in a Christian acquaintance’s home, she connected Emanuel to a former monk, who took him to a monastery where he would study for the priesthood under false papers. It was 1942.

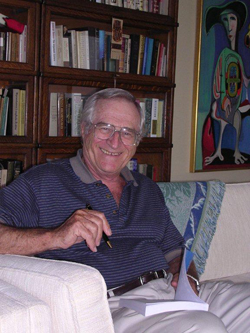

Today, Tanay lives in Ann Arbor. Though retired as a psychiatrist he continues to write extensively, including books on the Holocaust and the psychology of homicides. (Photo courtesy Emanuel Tanay.)

They survived by a millimeter. The very day after their escape, the Germans carried out the “final liquidation” of the ghetto, deporting every resident to concentration camps. (Despite his connections, Tanay’s father was ultimately murdered. His killer was SS officer Amon Goeth, played by Ralph Fiennes in the movie “Schindler’s List.”)

That narrow escape was the first of many. At the monastery, a teacher figured out Emanuel’s secret and denounced him to the Gestapo. He only escaped after hiding inside a church organ. Later, living on false papers as part of the Resistance, Tanay had to jump from a train when someone recognized him and shouted “That’s a Jew from Miechow!” He eventually escaped to Hungary, where he was captured and sent to a prison camp. He only survived by trusting a Gestapo agent who happened to be a member of the Yugoslavian resistance, and who arranged for Tanay and his comrades to escape.

He spent the rest of the war living on false papers in Hungary. Ironically, he was nearly shot by Russian troops who liberated Budapest—they didn’t believe a Polish Jew could have survived the war without being some sort of traitor. (Rather than taking his life, they settled for his winter coat.)

Even after the war, Tanay says, survivors encountered distrust and hostility similar to the Russians’. When he returned to his hometown, for instance, friends told him not to spend the night—the locals would kill him. Ironically, he found that the safest place was Germany. In Munich, Tanay earned a doctorate in medicine.

Bread under the pillow

In 1952, he was allowed into the United States, shortening his name from Tenenwurzel to Tanay on his way to attending post-graduate school at the University of Michigan. In many ways, he has not moved far at all from his Holocaust experiences.

In his private counseling practice, he treated many other survivors. “My wife could always tell when I’d been listening to a survivor,” he says, because his mood after work would be so dark. Survivors, he says, “all suffered PTSD, and I do too. One survivor told me, ‘I have no after-effects or problems at all, except one thing. I can’t fall asleep without a piece of bread under my pillow.'”

But helping fellow survivors was not enough for Tanay. He also dug deep into the opposite mindset, that of killers. He became one of the nation’s foremost experts in the psychology of murder, interviewing and sometimes testifying about killers from Jack Ruby to Ted Bundy to Sam Sheppard, and gathered his insights into a book called “The Murderers.”

Tanay and his wife Sandra now live at a less hectic pace. He’s still writing, and he remains outspoken, publishing essays as well as a third book, “American Legal Injustice: Behind the Scenes with an Expert Witness.” And his identity as a survivor, of course, will always be with him—along with its obligations. “Now survivors are venerated,” he says. But that veneration can make it too easy to think of survivors merely as victims, as objects of pity rather than active players in their own survival.

“Survivors are the forgotten heroes,” he says. “They needed courage, resourcefulness, the help of random events. Hope. “If you wanted to die, it was very easy. In no time flat you were dead.” Just to keep going, to play for time, required a great muster of will. Despite age and cancer, Tanay is a force, and he intends to stay one. “Upon my death,” he says, “I want no memorial, but a celebration. I had a good life. I survived, and I fought against injustice.”

Lisa Brush

John (and Emanuel)-

Thank you for sharing the story so eloquently. There is much that we can all learn from survivors – anyone who has come through any form of hardship. How we incorporate our experience into ourselves, our families, our friendship, our work, and our community is a choice that is made easier by having inspirational role models. Indeed our community is made stronger by having survivors willing to share their courage, resourcefulness, and hope to us all.

Thank you-

Lisa

Reply

Michael Nunn - UMSSW 1989

Dr. Tanay’s commentary about his experiences while fleeing the Nazis seems remarkable to me from two incongruous perspectives: One, that a significant segment of the European civilian population appeared ready and willing to betray Jews in hiding even when under no threat to themselves; and Two, that a Gestapo agent, of all people, would take an active role in helping Jews to escape, at extreme peril to himself. This is incredible material for a film. Thanks to Dr. Tanay for recounting his experiences, and to Mr. Lofy for publishing them.

Reply

Scott Larsen

What an incredibly moving story. We all learned about the Holocaust in history class, but to hear these first-hand personal recollections brings these events shockingly to life. A survivor’s words mean so much more than any textbook, novel or movie. They serve as a searing reminder of the very real human beings whose lives were forever changed by overwhelming forces beyond their control. Thank you, Emanuel, for having the courage to survive and then to keep vividly alive memories that must surely be very painful.

Reply

Hillary Rosenfeld - 1982

What an inspiring story…we hope Emanuel Tanay knows that by sharing his story he continues to teach and illustrated the values of courage, justice and will to live. I will forward this to members of my family (including my daughter who is completing her senior year now at U-M), but I wish I could share it with my recently deceased father who was a liberator in WWII and would have been most moved. Thank you for a beautifully written profile.

Reply

Renee Nixon

Thank you for your story.

Reply

Chester R Steffey - 1954, 1957

A stirring and sobering testimony. Thanks for making it avilable for us to read.

Reply

Holly Brauer Finstrom - husband is alumnus

My father escaped Germany with his parents and went to the Phillipines, which was the only country which had not filled its quota of Jews yet. They snuck out by pretending to take a vacation cruise to Holland. I am very proud of the fact that my middle class, not very educated grandparents saw the writing on the wall and made the decision to leave in time. My father lost all his other relatives except one cousin still living in England.

Reply

Marjorie Korenblit - 1965

Dr, Tanay’s history and that of other survivors is challenged every day by those who would deny the Holocaust occurred. It is our responsibility to stand up for the truth and prevent the trivialization of this horrendous epoch by referring to any act of murder or genocide as a “holocaust.” The Nazi’s systematic rounding up and mass murder of Jews with the active cooperation of other Europeans is without equal.

Reply

Nicole Holmes

Thank you for your story. I am enraged by people that belittle the history and violence of the Holocaust. If we do not “think for ourselves” instead of following blindly history will continue to repeat itself.

Reply

Sonia Hulman - 1971

Thanks to Dr Tanay for all of his work with survivors and for sharing his story so eloquently. It is all the better to read and feel a sense of perspective during these discouraging times.

Reply

David Rigan - 1970, 1973

I have always been interested in the idea of counseling or therapy (and possible use of prescription drugs). These are people who are forced to pay for treatment for being victims of a heinous crime perpetrated on millions. It’s double punishment. I don’t know if it’s true, but I heard that there no cases of any Nazi murderer of Jews who have had therapy for feelings of remorse (admission of guilt is a possible reason).

Reply

Connie Phillips

Remarkable writing. I was in Warsaw on 1August 2004–the 60th anniversary of the uprising. I was lucky enough to be close to a bookstore and purchased a copy of Norman Davies\’ \”Rising \’44\”–great book. What is so terrifying about the Holocaust is it really wasn\’t that long ago. We must never forget.

Reply

Elaine Dvorak - 1980

I thank you for sharing your true story and for helping all those who went through the same horrific pain you experienced. It shames me that there are true Americans that say the Holocaust never happened!!! I can not understand how they can believe that?? There is so much proof and living, survivors like yourself who can tell about it. I just thank you so very much for your story and pray we never allow something like that to ever happen again. Elaine D.

Reply

Elaine Tanay - 1975, BA, 1977, MSW

My father, Emanuel Tanay, the subject of this fine article died this past Tuesday August 5 at age 86. I treasure this article and the lovely afternoon John Lofy, my dad and I spent together.

Reply