For more than half a century, the system of As through Es that we take for granted—the system responsible for so much toil and anguish down through the generations of students—was quite foreign to the University of Michigan.

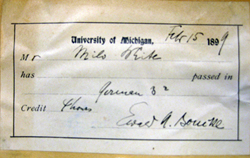

Before 1912, U-M did not give letter grades, but only passed students or failed them. In 1899, student Milo White passed German (above)…

In its early years, the state was populated by pioneering farmers loyal to the frontier egalitarianism of Andrew Jackson. In their eyes, the whole business of ranks, distinctions, and awards had the perfumed odor of European aristocracy. In the classroom, professors expected the Michigan student to meet a standard of hard work and intellectual attainment. If he—there were no “shes” at Michigan until 1870—proved he had done so in regular recitations and exams, he earned a “pass.” If not, the judgment was “fail” or “condition,” the latter meaning the student could be reexamined on the part of a course where he fell short. No further distinctions were considered necessary. No honor points, no pluses and minuses, no grade-point averages.

Since few academic records survive from U-M’s earliest years, it’s hard to determine how the earliest students were evaluated. But the no-grades policy was certainly in place by the Civil War. In 1866, President Erastus O. Haven, a classics scholar, explained that Michigan students were assumed to be both “competent and inclined to perform their duties without an appeal to the puerile ambition engendered by rank in classes and prizes and medals… It is doubtful whether these even promote good scholarship… and it is certain that they engender strife and envy, if not hatred…”The proper stimulants to study,” Haven added, “are not medals, or position in class, or prizes, but the gratification produced by an enlarged acquaintance with truth, and by the greater influence for good thereby produced.”

The greatest defender of Michigan’s policy was at first a reluctant convert. James Burrill Angell, president of U-M from 1871 to 1909, came to Ann Arbor from New England, where marking systems were standard. As a student at Brown, he had earned high enough grades to win election to the honorary society Phi Beta Kappa, and as president of the University of Vermont, he had presided over a faculty that graded its students. So Michigan’s system struck him as odd.

James Angell supported grading when he became U-M’s president, but soon changed his mind. (Photo Courtesy U-M’s Bentley Historical Library.)

Yet after a single year at U-M, Angell declared: “I may properly say that I am fully convinced by what I have seen here…of the uselessness of [a marking] system for students like ours. I have never seen a better average of class work than I find here in the classes of the teachers, who insist on having good work done by their pupils, and who possess in a fair degree the power of inspiring them with enthusiasm.”

The policy was in keeping with Angell’s vision for Michigan–that it should provide “an uncommon education for the common man.” Over his 38 years as president he argued repeatedly that “broader, heartier, better work” was done by those who studied simply “for the sake of learning” than by those who were merely scrapping for grades. “A collegiate course cannot be wisely shaped with primary reference to driving drones to work,” he declared. “It should provide every manly and noble incentive to worthy achievement.”

Of course there were students for whom no incentive worked. For them Angell had a simple solution. He sent them home. And he was no ivory-tower theorist. He was in the classroom every year, teaching a highly popular course in the history of international law. Angell thought a student’s weekly work was a better gauge of academic progress than his performance on high-pressure exams. A graduate of 1904, Charles Sink, recalled a period in Angell’s course when he finished his exam much earlier than his classmates. When Sink handed in the paper, Angell looked up “with much surprise,” since Sink had finished so early. A few days later, a letter arrived at Sink’s rooming house. It was a summons to the president’s office. Sink hurried over. Angell greeted him warmly but said his exam had been a poor job. He had looked up Sink’s record, the president said, and discovered not so much as a “condition,” let alone a “fail.”

He invited Sink to sit and handed him a bluebook with a new set of questions. When Sink finished this second exam, Angell read it carefully, then asked why this one was so much better than the first. Sink confessed that Angell’s original exam had been the third of three he’d taken that day.”Three examinations in one day is too much,” the president said. “That accounts for it, because your paper today is excellent. I am going to pass you.”

Other students in the class might have complained that Sink got a special break. But in this noncompetitive regime, the point was simply to evaluate how much Sink had genuinely learned, not to administer an arbitrary set of rules. Angell concluded that the test had been at fault, not Sink.

Angell stepped down from the presidency in 1909, and the no-grade policy barely outlived his tenure. Younger academics trained in highly competitive institutions thought grades were the proper carrots and sticks to induce harder work. Corporations and the professions were increasingly looking to colleges and universities to pick the brightest out of the bunch. And Michigan students—aware that their Ivy League rivals could boast of high grades—added their own demands for a system of honors and distinctions.

Phi Beta Kappa established its first chapter at Michigan in 1907, and in 1912 the faculty approved an across-the-board system of awarding grades for each course from A through E. To students, the innovation would soon seem to be a grim fact of nature, as inevitable as winter following fall. But those who yearn for some better inducement to learning than the weary scramble for grades might think over the example and advice of President Angell.

“One of the encouraging signs in our American collegiate life,” he wrote in 1874, “is [the] willingness to admit that possibly something yet remains to be learned about collegiate methods and the courageous readiness to try new ways.”

Sources included the President’s Reports to the Board of Regents; “The University of Michigan: An Encyclopedic Survey”; The Chronicle; The Michigan Daily; and Shirley W. Smith, “James Burrill Angell: An American Influence” (1954).

Terrell Rodefer - 1961

Starting in the 7th grade, a group of us started a friendly competition to outdo one another scholastically– “us” meaning those who felt inclined to be a part of that particular group of students. As I wanted to fit in somewhere, this group was the one that appealed to me the most. That meant studying harder and learning material in order to pull good grades. The competition had a terrific effect on our workmanship. This continued through high school, as most of the same students continued from one school to the next. Many years later, as a high school teacher, I saw the same impetus driving students under my tutelage. There simply are able students who strive harder to reach the top if there’s a yardstick to measure their accomplishments by, and competition pushes this.

If just the fact of learning and knowing isn’t enough, it’s still a byproduct of wanting to beam over those good grades.

Reply

Denise Love, PhD - 1975

I am an educator having taught for over 35 years now and I have never believed in grades. Grades has led to competition in the classroom and has caused students to feel less about themselves than they should. The competition has led to the violence in our classrooms. Grades do not mean anything in the real world but hard work does. I have seen great strides in classrooms where students work to learn and not work to get the almighty good grade. I am all for no more grades!!

Reply

David Haldeman - 1973

Back in the early 70’s I took a Poli Sci class that – at the time – was part of a non-grading assessment. You either Passed or Failed.

I had the opinion that the University was exploring this option. I do not know why this class was chosen or how many others were included in the assessment. But our professor was quite forthcoming in his assimilation of it. We were told at the very first session that if we completed the assignments and basically showed up for class we could expect to Pass.

Now I was not majoring in Political Science, it was an elective course, so it did seem to effect my level of dedication to that class. I was after all programmed throughout my schooling years to work harder and get better grades. Without them as a measurement I would not have been accepted at U of M.

I did receive a Pass in the course, but I had no idea how well I had really done. This was to be my only Pass/Fail course. My opinion of it: It was not challenging and rather easy to get through… but unsatisfying.

Reply

George J Bacalis - June 1956

There are two points that I would like to make from my personal experience at the University of Michigan and it’s grading system.

Sixty years ago, during the Christmas holidays preceding “finals” ending my freshman year, I was severely injured when hit by car. I spent the “finals” period as a patient in University Hospital and consequently missed all my exams. Regardless of success during my first semester I was put on “Probation” because I had a half dozen incomplete grades. At the end of my first semester sophomore year I took about a dozen exams including my make-up exams, did quite well, was lifted off probation and went on to eventually graduate with a GPA somewhere around a 3.5. It has always troubled me that I was placed “on probation”, which must be obvious since I am writing this approaching my eighty-ith birthday. There must be many many students today who face a similar circumstance, especially so with a student population twice what it was in the 1950s. The University should have a category other than “probation” for such students because it taints their transcript and possibly their employment future.

My second point is that as a student in the School of Architecture and Design there was course work which were graded “A through E” and also “Pass or Fail”. Since I have experienced both grading systems, my preference had always been a letter grade. The reason for this was, despite the fact that I was very competitive oriented and ran track on the team, I found that I along with other students did not perform at our level best when working only to pass and to not fail. Now, as I look back at that experience, it is like saying to an athlete that it is good enough to be chosen to run an event and to not be given the incentive to win the race. In my opinion and humble experience of fifty -six years since graduation, a “pass or fail” grading system can only lead to less effort and a lesser overall individual capability. Make the students run for the roses in every class. It is best for all.

Reply

Laura Bien - 1990

Fascinating new info to me; thank you for this absorbing article.

Reply

David Richardson - 1995

Some people are completely self-motivated. Others work better under some outside pressure. For some, the pressure to outdo your peers can be crippling.

As for me, in my young adult life being under a grading scheme for core- and major- courses with the option of taking other courses pass-fail helped me achieve my goals. No doubt some of my peers would’ve been better off in a totally pass-fail environment.

Reply

Sara Thiam - 2004

If I am not mistaken, the Residential College, housed in East Quad, functions on a no-grade system for those who choose that option. Qualitative evaluations are done. The rigor of the school is no less than that of its graded counterparts, but I do not know how motivation to perform, or intellectual development might differ from other UM schools.

Reply

Leonard Wolons - 1987

I was working full time as a Police Officer when I transfered to Michigan after acquiring an associate degree in crim-justice from Schoolcraft with a 3.9gpa. The first paper I wrote whould have been an A+ at Schoolcraft was adorned with red ink and a request to “try again”.

Reply

Claire Cameron - 2002; 2007

This is a fascinating topic at all levels of education and accomplishment. I’m concerned that we rely too much on reward systems (like grades, but even processes like tenure) with the consequence that learning no longer happens for its own sake. I wonder whether over a long period of time, and after pursuing these rewards essentially for their entire lives, individuals can become highly accomplished in their fields but still be missing important life skills like wisdom, judgment, self-awareness, regard for others and my favorite quote from the article, “an enlarged acquaintance with the truth.” The decision to give the student who was on his third exam of the day another go seemed to be based on wisdom. I’m grateful for this article as an example of a time in our history when people used factor beyond grades to determine knowledge. More on learning and personal growth at: http://michiamochiara.blogspot.com/2011/04/more-about-learning.html

Reply

Jeff Lutz - BA 1977 (and fraternity brother of Tobin)

I always look for and enjoy Jim Tobin’s pieces in “Michigan Today” — always very interesting.

In terms of grades, UofM was not very good at calculating grade points in the mid-1970’s. I was in the Marching Band, and as part of MMB I was supposed to receive 2 credits in the fall term every year, with no grade attached. But for some reason, the credits always came through as 3 credits with an “A” attached. And of course, Michigan did not count pluses and minuses in the grade point until the fall term of 1976-77 academic year (and I was always very good at the A- and B- grades!), so my gradepoint was further inflated. As my son (also BA in Economics, but in 2009) compared his specific grades to mine 32 years earlier, his 3.57 GPA would have been higher than my 3.77 had the rules been interpreted the same way! So gradepoints are really not very scientific — and actually are quite inaccurate.

Keep up the good writing, Mr. Tobin!

Reply

Robert Selwa - 1984

If the emphasis is put on learning the subject and material, and the educator is enthusiastic and knowledgeable, all the instructor has to do is make sure the students obtain from the class what he or she believes important, and that the student reaches the level of competency required. Maybe pass, fail, and outstanding would solve the problem for excellence. When you add the stress of the cost for an education, along with a system of very competitive grades, I think you lose sight of using the learning process to enrich one’s interests, and intellectual abilities and the benefits this brings to society at large. I think grade slaving debases the morale for enthusiasm in the educational process if too strictly observed and followed.

Reply

Joe McMaster - 2007

The sad fact of the “A through E” system is that you end up the saying “C’s get degrees”. I have lost count of the people I’ve met that got an A and three months later lack the ability to perform what they supposedly mastered. We as a society have lost proficiency in favor of weak attainment. In my experience, professors today in pass-fail courses treat a D as a pass and thus undermine the idea. If an A was equivalent to a pass and an E to a fail with condition used in between, we would have room for a fair dialog. The scariest issue to me is the great variance in competency of college graduates which causes a host of problems both socially and productively to our society.

Reply

Erik Kuszynski - 1992

Statistics professor Ed Rothman preached that grades were, at best, an estimate of the knowledge a student in a particular subject. He encouraged us to strive for knowledge and not sweat the grades. If you know the subject, the grades normally follow, though they will not always be accurate.

Instinctively I knew this to be true, but I was still striving for good grades.

Then I took econ 201 and 202 concurrently and struggled mightily. I put more effort into those two classes than I ever had in my life, yet could only muster a C and C-. Not because I didn’t know the material, but because the TA’s in both classes failed to prepare us for the exams. I wasn’t prepared for the questions that the professors asked about minute details of the course material.

It was only then that I realized that grades are not always an accurate assessment of knowledge and that knowledge, not grades, was the purpose of learning.

This realization was a great gift and I know it will serve me well as a parent. Thank you, Professor Rothman!

Reply

Steve Salterio - PhD 1993

As a professor at one might consider a peer institution in Canada (Queen’s University) I have a very hard time convincing fourth year students that what I want is really for them to learn about the subject matter as they have been so socialized to grades that the marks become the learning. It takes me most of the term to convince them that if they demostrate understanding and mastery of the material, however late in the term, they will receive the same grade as those who demostrated it continually throughout the term. Mind you I mark about 25 assignments plus a midterm throughout the term so the students know that I am monitoring their learning and intervening actively when I am not successful in helping them learn. I think that UM’s orginal approach is far superior for promoting learning but unfortunately our univesity has just passed a proposal to do away with a six bucket system to the “more common” letter grade plus/minus system. More grades less learning.

Reply

matthew schmalzigan - 2003

“What do you think? Did academia take a wrong turn by implementing grades? Do you have a good story about grading?”

I really never cared about my grades while in school. I was there to learn. I saw many students copy or regurgitate information to attain high grades – in fact this was the rule. I thought that if I followed them and competed against them, I would not get my money’s worth from my education. I decided to read everything, do the exercises, think and analyze without consulting my peers. I did this even if my assignments were late and I would get zero credit. In the long term, it was a great decision. I continually smoke my colleagues now, because they do not have the same depth of understanding as I.

Reply

Nurit Zachter

I went to undergraduate at a school that did not give grades but instead gave written evaluations. Much more work for the instructors but much more valuable for the students.

Reply

Joel Davidson - 1991

I think President Angell was ahead of his time! As a teacher and guidance counselor, I have multiple conversations each week about the idea of learning for its own sake, and the grades will come naturally. Today, the pressure to get good grades outweighs the notion of learning for its own sake. It is truly a shame that our education system promotes high stakes learning, because in all honesty, it is not learning. It is memorizing for the test, and then forgetting or barely remembering at all. What a pity. Maybe it is time for us to re-think education and encourage our students to love learning. No doubt many do so on their own. Perhaps removing the excessive pressure would result in better and more knowledgeable students. One could only hope! Thank you for this fascinating article. Go Blue!

Reply

Carl Stein - 1982

Thirty years ago I was a student in the Residential College. At the time (I don’t know whether it’s still true) all RC courses were graded pass/fail plus a written evaluation from the instructor. Depending on the course and the instructor, the written evaluations could be full of wonderful, positive feedback on a student’s performance; devastating; or barely noticed. The knowledge that there would be a forthcoming written evaluation made it difficult to just coast to a pass. The written evaluation was much more informative and descriptive of a student’s performance in class than any letter grade. I also took non-RC courses in LSA where grading was A-E. The pass/fail RC courses provided a more satisfying and friendlier learning environment without the distraction and disturbance of focusing on letter grades and competition with classmates. The absence of letter grades encouraged learning in the pursuit of a broad education rather than a lettered reward. The absence of letter grades also allowed a student to take RC courses outside his strongest field without fear that he might get a C, which could ruin his GPA. I remain grateful for the RC’s educational approach when I was a student there, and I hope that today’s RC students have the same opportunities and benefits that I had and receive the same excellent education that I received.

Reply

Jane Poling - 2009

I had severe academic culture shock last year when I got my masters degree abroad. Oxford University operates under the Distinction/Pass/Fail system, and the only contributions to my final outcome were from a series of high-stress exams. There really are pros and cons to both systems.

Reply

Herb Bowie - 1973

Fascinating bit of Michigan history. I have to say that I find this same sort of grading system to be heavily used in corporations, and with problems similar to those reported by Angell: corporate drones focused on getting raises and bonuses, rather than on actually improving the operations of their departments.

Reply

Harvey Hausmann - 1995

I remember one semester I was taking 6 classes. My finals schedule was horrible. The first two classes I had plenty of time to prepare; however, the last four exams occurred over a period of 36 hours with three exams in one day and the fourth the next morning. If I remember correctly the University’s policy at the time was that four exams had to be scheduled on the same day in order to reschedule. Needless to say I did not perform as well on the last two exams, particularly the last exam. I was simply mentally exhausted. That is why President Angel’s action with Sink struck a chord in me. As far as the no grade system, I think it would be a great boon to those students that have trouble understanding material right away. There would be less discouragement and less damage to their self-esteem.

Reply

Kelly French - 1989

This article was really interesting, and even more so for me right now as I have friends and relatives who are currently in the teaching profession. I live in Florida which is in the process of changing how they evaluate their teachers annually, and an area where schools even receive a letter grade of A-D or F. Maybe we all need to go back to a system like Angell’s and look at a pass/fail rating to measure accomplishments. The current system is not working and the proposed system makes even less sense.

Reply

Jim Pistilli - 74, 79

As a college professor for 12 years, I can tell you that any grading system is subjective. The best students are self motivated and have a genuine thirst for knowledge. Their grades are irrelevant to their success after school. Few companies ask for your transcript once you are out of college. Why do you suppose. The proof is in the pudding.

Reply

Amy Olszewski - 2001

I’m an alumna of the Residential College, and about half of my classes were graded Pass/Fail with the narrative evaluations described in previous comments. I learned more about myself, my abilities, and how to improve by reading those evaluations as opposed to the letter grades I received in other classes. I admit that I worried about getting into graduate school without a “real” GPA, but schools know how to calculate them. At the same time, I strongly believe that my RC evaluations played a huge role in my admission to graduate school. Thanks, RC!

Reply

Ted Hall - 1979, 1981, 1994

Last month I had the displeasure of assigning a failing grade to a student. He’s a good guy, but was over-extended and other courses had higher priority for him. He had wanted to drop this course but was informed by the university bureaucracy that it was too late — that he would receive a failing grade if he dropped. It was a no-win situation for him.

While letter grades might provide some incentive to better performance, I think that students should be allowed to drop a class at any time if they’re failing it, with no damage to their GPA, and retake it as many times as necessary to master the material. There would be less distracting pressure, less cheating and more genuine learning.

There are many reasons a student might not pass a course on the first try, that have nothing to do with intelligence or diligence: underestimation of workload; illness or injury; family problems; loss of project material due to computer theft or damage, … These shouldn’t taint a student’s GPA for the rest of his academic career, but the current system makes do allowance for any of this.

What matters in the end is what was learned, not the missteps on the way to learning it.

Reply

Tom Dotz - n/a

In the ’70’s the new campus of the University of California at Santa Cruz conducted itself as a grade-free institution. In the Reagan era of the 80’s the change to grades was instigated for the same reason: to provide corporations with a service, the ranking of students. Interestingly, there also, the impetus was from the students. The campus was actually losing enrollment due to its rather enlightenment approach: students were given written evaluations by each professor.

Reply