Roger Ebert on the page and on the screen

As an aspiring documentarist in 1994, Steve James received a life-changing career boost by legendary film critic Roger Ebert.

James spent five years shooting the documentary Hoop Dreams about two inner-city Chicago boys who dreamed of making it to the NBA. Ebert named the documentary the best picture of the year. Six years later he named it the best film of the decade. In his review of Hoop Dreams Ebert wrote, “No screenwriter would dare write this story: It is drama and melodrama, packaged with outrage and moments that make you want to cry.”

These comments were typical of the kind of regard Ebert felt for great movies and for the inherent possibilities of cinema itself.

The book

In late 2012 Ebert and James began discussing the idea of a documentary about Ebert’s own life, framed by the critic’s 2011 memoir, Life Itself.

In late 2012 Ebert and James began discussing the idea of a documentary about Ebert’s own life, framed by the critic’s 2011 memoir, Life Itself.

Ebert’s memoir is an introspective literary journal, created with some urgency after recurring bouts of salivary and thyroid cancer ravaged his body. First diagnosed in 2002, Ebert ultimately was unable to speak, eat, or drink. But two vital things remained intact: a brilliant hyper-active mind and facile fingers that could attack a computer keyboard with relish.

Ebert took to blogging and never stopped writing film reviews. He attended screenings as long as he was able, and then he viewed films at home on DVD. (His last review — of Terrence Malick’s To the Wonder — was published two days after Ebert’s death on April 4, 2013, at age 70.) It was his facility for blogging that led to Life Itself. Ebert writes in the memoir’s introduction: “My blog (begun in 2008) became my voice, my outlet, my ‘social media,’ in a way that I couldn’t have dreamed of. Into it I poured my regrets, desires, and memories. Some days I felt possessed.”

In the memoir Ebert traces his life with his family as a youngster in Urbana, Ill., where he would later attend the University of Illinois. There he wrote for and served as editor of the student newspaper, the Daily Illini. At the paper and on campus he was known for his brashness, and Ebert admits in the memoir, “I had become a cocksure asshole . . . As editor I was a case study. I was tactless, egotistical, merciless, and a showboat.”

The gift

But overriding Ebert’s “character flaws” was a gift for writing and for recruiting other gifted writers to the paper. In 1965 a Rotary Fellowship took him out of Urbana and to adventures in Cape Town, Vienna, and finally London — a city he fell in love with and which, later in life when he no longer could walk, he would revisit in his mind.

One of the 20-some books Ebert would write during his lifetime was The Perfect London Walk, co-written with Dan Curley and published in 1986. I was in London when Ebert died and I went in search of the book, which had been widely noted in obituaries in the London papers. I found a copy in a Hampstead Village bookstore and followed Ebert’s guided tour into Hampstead Heath and up to Parliament Hill for the treasured views of a distant London. Ebert’s unwavering love of London and Chicago are time and again conjured up in his blogged memoir.

One of the 20-some books Ebert would write during his lifetime was The Perfect London Walk, co-written with Dan Curley and published in 1986. I was in London when Ebert died and I went in search of the book, which had been widely noted in obituaries in the London papers. I found a copy in a Hampstead Village bookstore and followed Ebert’s guided tour into Hampstead Heath and up to Parliament Hill for the treasured views of a distant London. Ebert’s unwavering love of London and Chicago are time and again conjured up in his blogged memoir.

Other “fragments” of recollection — as Ebert describes his memoir-writing process — include his appointment at age 25 as film critic of The Chicago Sun-Times; eight years later in 1975 a Pulitzer Prize for criticism (the first-ever for a film reviewer); the launching in 1978 of “Sneak Previews” on PBS-Television with co-host Gene Siskel, his counterpart at The Chicago Tribune (who came to be “less like a friend than like a brother”); and, finally, his marriage at age 50 to Chicago lawyer Chaz Hammelsmith, a woman whose enduring love and care amid the devastation of cancer “was like a wind pushing me back from the grave.”

A slight detour

A lively part of Life Itself comes in Ebert’s recollections of interviews with famous film actors and directors, and especially in his association with skin-flick director Russ Meyer. Ebert first came to know Meyer in Chicago after a screening of the director’s Finders Keepers, Lovers Weepers! (1968), and the two remained acquaintances. In 1969 Ebert was offered the job of scriptwriter for Meyer’s parodic soft-core film Beyond the Valley of the Dolls (1970). Ebert describes this film (not very well received) and other filmmaking ventures with Meyer through amusing and sometimes saucy anecdotes.

http://youtu.be/V6155Lu6AfI

Reading about Ebert’s working jaunts into the business of filmmaking, I was reminded of other established film critics who’d been lured to Hollywood over the years.

James Agee, a great film critic at The Nation and Time in the 1940s, quit the magazines in 1948, moved to Hollywood, and co-wrote screenplays for two classic films, The African Queen (1951) and The Night of the Hunter (1955), before returning east to resume writing fiction. After his 27-year tenure as New York Times film critic ended in 1968, Bosley Crowther took a job as a script consultant for Columbia Pictures. In 1979 the esteemed Pauline Kael left The New Yorker magazine for bigger pay in Hollywood and had a very bad experience as a writer on Paramount’s Love and Money. The studio fired her, and after less than a year out west Kael was back in New York.

Ebert’s experience in Hollywood ended with an aborted 1977 Russ Meyer project involving the seminal punk band the Sex Pistols. The story concludes with Ebert attending Meyer’s funeral at Forest Lawn Cemetery in 2004, decades after Ebert’s full-time return to movie criticism.

Life Itself has its own interior literary life, much like an epistolary work in which the writer offers first person, direct access to what one is thinking about and is compelled to put into words. The final epistolary “fragment” comes in the memoir’s last chapter, “Go Gently,” as Ebert writes candidly about facing death.

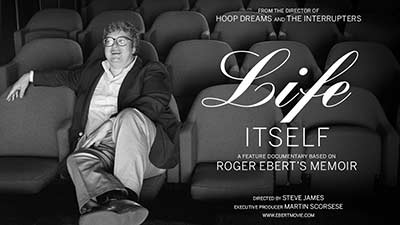

The film

In late 2012 when Steve James and Roger Ebert began discussing a screen version of the memoir, they hoped to turn the narrative fragments of the book into a tribute to Ebert’s storied career. But a new bout of metastatic cancer altered what the documentary could and would be. At Ebert’s encouragement James filmed Ebert in his hospital room, in what would be barely three months of remaining life. No matter how much of Ebert’s fascinating history is sketched out in the documentary — through photo montages of childhood and college years, personal and professional film clips, talking-head interviews with colleagues, friends, and family — a funereal aura permeates the work.

While Life Itself on the screen is inherently different than Life on the page, it is no less powerful. First, the film not only projects a story of a man of unquestionable talent, but also a man of extraordinary courage met by the equally extraordinary strength of his wife. In a reversal of narrative construct, Chaz Ebert (who had no first-person voice in the memoir) assumes the role of creating a paean to her husband. Even as she agonizes on camera over what fate has brought to the couple, she praises her husband’s unflinching determination not to hide the extent of his illness. In the film’s most indelible scene, a medical technician uses a suction tube to clear Ebert’s airways. The openness with which Ebert allowed — insisted — that he be filmed is both painful and cinematically revelatory.

“The imperturbable camera”

As I thought about the dark side of the film, I was drawn back to ideas I first came to appreciate in Siegfried Kracauer’s brilliant treatise Theory of Film: The Redemption of Physical Reality (Oxford University Press, 1960). Kracauer argued in his book that the motion picture medium holds possibilities for exposing aspects of human existence the mind’s eye might otherwise have shunned: death, atrocities of war, acts of violence, etc. Kracauer says it is the motion picture that can keep “us free from shutting our eyes to the blind drive of things,” and he attributes this cinematic function to the “imperturbable camera.”

Indeed, it is the presence of James’ camera in Life Itself that works to this perceptual end. It is testimony to the human spirit that the viewer is permitted access to such non-sentimental courage and determination in a dying man and his devoted wife. Most compelling is a final sequence in which James, aware of the critic’s impending death, begins to bombard Ebert with email questions. In a rapidly flowing montage the questions and answers are visualized on screen until James’ request for more answers is met simply and directly with an email reply from Ebert: “I can’t.”

Could there be a more elegant, perfect way to reveal that a great critic’s “voice” has come to rest? Powerful filmmaking.

A final thought: When I want to refresh my memory of what made Ebert such a respected and diversified film critic, I return to his collections of retrospective reviews, published in three separate volumes titled Great Movies (I 2002, II 2005, III 2010). The passion, the wit, and the broadness of Ebert’s range can be found there.

scott newell - 2002

Hi Frank I am always in admiration of your genuine love and respect for the beauty inherent in others. Thanks again for sharing.

Reply

Robert Megginson

One comment in this piece about Roger Ebert brought back some memories, and I admit that I’m about to do a name-drop. I actually knew Roger fairly well due to an alignment of some stars. I was intensely involved in student government at Illinois during part of the 1960s, and spent some quality time in the offices of the Daily Illini (called the DI by all) talking about different issues during an interesting time in campus history. I note the comment about Roger’s characterizing himself: “As editor I was a case study. I was tactless, egotistical, merciless, and a showboat.” I can see Roger criticizing himself that way, but it really didn’t come across as such. He would say what an editor would have to say to get an interviewee to open up on a topic (and I was the “victim” at least once), but when you walked away at the end you never got the feeling that you had been run over by a truck, just that you had engaged with someone who knew how to do his job. Despite his self-characterization, “professional” was the short phrase that comes to my mind. And the world did lose a powerful figure way too early with the end to his struggle with cancer.

Reply