Letters of note

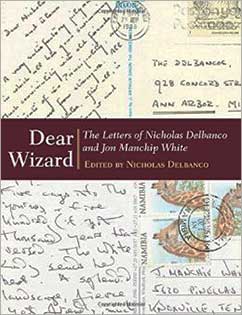

In late 2014 the University of Michigan Press published Dear Wizard: The Letters of Nicholas Delbanco and Jon Manchip White. The publication coincided with Delbanco’s retirement from U-M, where he served as director of the Master of Fine Arts in Creative Writing Program, as well as the Hopwood Awards Program in the College of Literature, Science & the Arts.

At nearly 750 pages, the book is s a full-sized facsimile reproduction of the bulk of correspondence between two writers — one that terminated only with the latter’s death in 2013.

As Delbanco explains of Dear Wizard: “This enterprise was planned and prepared for while both authors lived; it grieves its editor sorely that but one of us has seen it to fruition. The book was a labor of love for me, as well as a ramble down Memory Lane.”

Delbanco arrived at U-M in 1985; he is the author of nearly 30 books of fiction and nonfiction. Manchip White was a distinguished Welsh-American writer who published more than 30 books of fiction, nonfiction, and poetry. He also penned scripts for film and television.

In the following essay, Delbanco reflects on the joy he and Manchip White derived during 35 years of unique, whimsical, and old-fashioned correspondence, which chronicles the deep affection and mutual respect that defined their friendship.

Words with friends

The habitual exchange of letters is a custom now nearly extinct. There was a time when letter writing served as the necessary discourse for men and women not within earshot or in a shared room.

That time has gone.

The telegram and telephone, a cellphone or email, text message or Skype, the various new forms of telecommunication — Facebook, Twitter, and the rest — have each in turn displaced and finally replaced the habit of correspondence; few practice it today. Those who read collections of letters hereafter will read about the fast-receding past.

My own past recedes; so did that of Jon Manchip White. I have begun my eighth decade; he reached the end of his ninth. This collection spans the period 1978 to 2013. Our “habitual exchange of letters” therefore lasted not merely for years and decades but centuries, millennia. We shared rooms and cities but only seldom spent uninterrupted time in each other’s company, with no need to write. I could have wished it otherwise — have wished, I mean, to live more near and see with greater regularity a man I both loved and revered. What we have here instead is the record of a friendship attested to by correspondence and enacted largely in the epistolary mode.

These last two words suggest a kind of formality, an archaic-sounding language-set. It’s fair to say that some of what the book contains will seem, to some, arcane. We two were “men of letters,” and it’s not a phrase that either disavowed. For the years encompassed here, we stayed busily at work. Though much of the volume deals with matters personal and familial, a central theme throughout is the professional life. Between us we published more than 60 books of fiction, poetry, and non-fiction; we edited and introduced an additional 15.

I spent the bulk of my academic career at Bennington College and the University of Michigan, from which I’ve just retired as the Robert Frost Distinguished University Professor of English. Manchip White served as the Lindsay Young Professor at the University of Tennessee, Knoxville. We founded writing programs, paid visits to each other’s sponsoring institutions, taught together in summer creative writing workshops and academic courses of study in Vermont and London.

We dedicated texts to each other and solicited each other’s editorial advice. Further, we collaborated on a project, “Hotel de Dream” — first as a novel, then as a screenplay — which was at length abandoned. Almost every letter discusses at least in passing the hopes and fears and challenges attendant on a creative or research-based project: the lifelong work of words.

Paper chase

Nicholas Delbanco’s wife, Elena Delbanco, enjoys lunch with Jon Manchip White in London, mid-’90s. (Image courtesy of Nicholas Delbanco.)

At an early point in the correspondence, we stumbled on the notion of “borrowed finery,” and began to write on letterheads from points far-flung or obscure. Born in England, I came to the United States when young; White, born in Wales, arrived in America in middle age. Both of us traveled a good deal. These letterheads also should speak for themselves, but it became a point of honor to address each other on stationery from hotels and institutions and places — a Cuban jail, the White House — attesting to worlds elsewhere. (One of my titles is Running in Place: Scenes from the South of France, and White wrote several travel books, as well as The Journeying Boy: Scenes from a Welsh Childhood.)

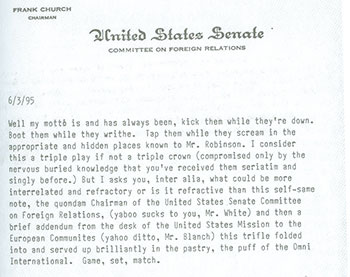

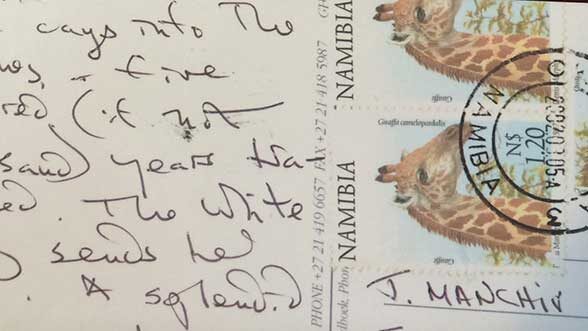

This joke soon enlarged into a contest, a kind of jockeying for position, and often the letters begin with the assertion that X has bested Y by mailing, say, a letter from those who flew across the Burma Hump or broke ice in Antarctica. There are claims of at-least momentary affiliation with or residence in the Supreme Court of Ohio and the Council on Foreign Relations, a school in rural China, the Inn at Foggy Bottom, the Pudong Shangri-La, Vienna’s Hotel Sacher, and Swakopmond in Namibia (“Where the Skeleton Coast Comes to Life”).

The envelope, please

In this excerpt of a letter from Delbanco to Manchip White, the author declares, “Game, set, match,” on acquiring letterhead from the United States Senate Committee on Foreign Relations. Enlarge to read.

Often the envelopes “doubled” the score, so that a letter from Jordan would be sealed inside an envelope from Brazil. To correspondents spending hours at their desks, such evidence of travel seemed both a release and relief. Most of this stationery was acquired by the authors as a result of actual visits; some sheets were provided by voyaging friends in the service of our competition, and set aside for use.

We placed an annual bet on who would score more “points” for eccentricity or exotica and kept our own, admittedly biased, running tally of results. We reveled in the back-and-forth, the stationery gathered or collected by those referred to as “agents.” Particularly daring forays were made on each other’s home turf — so that, for instance, I purloined stationery from the Reform Club in London while there on a visit with White; in turn he snatched sheets from the Michigan League and Ann Arbor Campus Inn.

At the end of each year a bottle of 16-year-old Lagavulin whiskey was the prize, with the proviso that the bottle then be shared. To the pair of us, this seemed like a game worth playing; to a readership it may seem self-indulgent but, to quote an unrepentant Gloucester speaking of his bastard son, “there was good sport at his making, and the whoreson must be acknowledged.”

Had I 50 more such letterheads, I would deploy them here.

Karen Lewis - 1965, 1968

As a weekly composer of hand written letters, I thoroughly enjoyed this account of the competitive correspondence of such good friends. My stationery consists of blank cards that speak to me from various indie bookstore shelves. I must have a couple hundred in my collection, some purchased with a specific recipient in mind. The only competition here is that the card must cost $3.00 or less. Imagine the fun of buying truly expensive cards at half price! The only disappointment is that I rarely receive a letter back. Must be writing to the wrong people, but they are my people, and I can’t not.

Reply