Bearing a burden of guilt

Many years ago – many, many years ago – I took a class in modern American intellectual history from the brilliant Robert Sklar at U-M. I remember him discussing the Great Depression, not in its economic or political dimensions (as most scholars did) but in its psychological one. Sklar talked about how many ordinary Americans then suffered under a tremendous burden of guilt – guilt that they were personally responsible for the country’s doldrums.

Many years ago – many, many years ago – I took a class in modern American intellectual history from the brilliant Robert Sklar at U-M. I remember him discussing the Great Depression, not in its economic or political dimensions (as most scholars did) but in its psychological one. Sklar talked about how many ordinary Americans then suffered under a tremendous burden of guilt – guilt that they were personally responsible for the country’s doldrums.

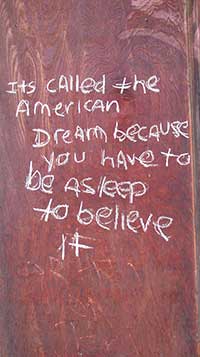

I often think of that lecture in these post-recession days when another generation of Americans is burdened with the same self-blame. You could say both generations were victims of the American Dream – a dream that, as James Truslow Adams, who coined the term, put it, “each man and each woman shall be able to attain to the fullest stature which they are innately capable, and be recognized by others for what they are, regardless of the fortuitous circumstances of birth or position.” Or put more prosaically: Work hard in America and you can achieve anything of which you are capable.

The problem, and the source of that personal agony, is that it increasingly isn’t true, which is something that endangers our economic well-being, our political well-being, and, perhaps above all, our psychological well-being. You can work very hard in America and not succeed at all.

And yet, there is a glimmer of hope, and it survives right here at our beloved University. The surest way to restore the dream and level the playing field in this country is to provide every deserving young man and woman the chance to get a first-rate higher education.

So one of the most profound questions facing this institution is: Can the University of Michigan save the American Dream?

Dreamweaver

Like so much else in American life, the dream was not a spontaneous eruption from the grass roots. Author/historian Adams introduced the term in his book The Epic of America, written, fittingly, in 1931 at the depths of the Great Depression when Americans needed to believe relief was at hand – in their own hands, if need be. In a way, the dream became a form of wishful sustenance – something Americans could hold onto, something that made them special.

When people talk about American exceptionalism, the dream is one of the fundaments. No other country thinks of itself in quite this way. As the essayist David Kamp put it in Vanity Fair, “As a people, we Americans are unique in having such a thing, a more or less National Dream,” adding that “it is what makes our country and our way of life attractive and magnetic to people in other lands.”Where Americans may be most exceptional, however, is not in the realization of the dream but in their belief in it. According to a Pew Research Center report, Americans believe more fervently in self-determination than the citizens of any other country. Only 36 percent of Americans agreed that success in life was determined by forces outside their control. So if they fail, they have no one to blame but themselves. By comparison, three-quarters of Germans believe that success is determined by outside factors.

This doesn’t speak to national differences in opportunity. It speaks to differences in perception. In actuality, as Pew concludes, Americans actually have less control over their success than the citizens of most other industrialized countries.

Our exceptionalism may be that we are exceptional dupes.

The dream in decline

But something nonetheless is happening to undermine that belief. Survey after survey has shown that Americans’ faith in the dream is declining as the economy has declined. A recent New York Times poll found that only 64 percent of Americans still believe in the American Dream, the lowest number in two decades and down eight percent from the worst of the last recession. A Bloomberg poll had almost identical results. By 64 percent to 33 percent, Americans felt the “U.S. no longer offers everyone an equal chance to get ahead,” and even 60 percent of those with annual incomes above $100,000 thought the economy “unfair.”

But something nonetheless is happening to undermine that belief. Survey after survey has shown that Americans’ faith in the dream is declining as the economy has declined. A recent New York Times poll found that only 64 percent of Americans still believe in the American Dream, the lowest number in two decades and down eight percent from the worst of the last recession. A Bloomberg poll had almost identical results. By 64 percent to 33 percent, Americans felt the “U.S. no longer offers everyone an equal chance to get ahead,” and even 60 percent of those with annual incomes above $100,000 thought the economy “unfair.”

In a 2013 Gallup Poll, 43 percent said the average American isn’t likely to get ahead, while only eight percent expressed that sentiment in 1952. And 73 percent of respondents in a 2007 poll by Pew – before the recession – agreed with the statement: “Today it’s really true that the rich just get richer while the poor get poorer.”

All of this is relevant when you view the task that U-M and other great institutions of learning have ahead of them if they are to revive the dream. Basically, they have to reverse the last 30 years of American economic history.

Running down a dream

To be honest, the prognosis isn’t encouraging because the patient is near comatose.Of the many lenses through which to examine the state of the dream, the most basic may be to tote up the cost of what we generally think the dream constitutes in terms of our social and material welfare — things like owning a house and a car, being able to feed our family and cover its health costs, saving for our children’s education and our own retirement, and paying our taxes.

Last year USA Today added up the sticker price of the dream, using standards like a $275,000 home with a 10-percent down payment and a four-percent mortgage, and an SUV. The price tag came to $130,357, not adjusting for regional differences. This income would place a married couple in the top quartile in America where the median income last year was just over $50,000. So roughly three-quarters of American households, by this metric, could not afford the American Dream.

But pure cost is not what most people think of when they think of the dream. They think of social mobility – of the ability to rise above one’s social class by dint of hard work. On this metric there is some good news and some bad news. The good news is that, according to a recent study by economics professors Raj Chetty of Harvard and Emmanuel Saez of Berkeley, the rates of social mobility in America have remained remarkably stable over the last 20 years. This is to say that alarmists warning of falling mobility have been dead wrong. That’s the good news.

The bad news is that those unbudging rates are miniscule. Only eight percent of children born into the lowest income quintile rose into the highest quintile. Only 20 percent in the middle quintile achieve the same rise. By this metric, the American Dream hasn’t really been shattered. It never really was – at least not for the past 20 years, and, by earlier studies, perhaps 30 years before that.

Going mobile

This is what is known as relative mobility, meaning, as the Economic Mobility Project conducted by the Pew Research Center, puts it, that “boats are changing places but says nothing about the strength of the ride.” Pew’s survey corroborates Chetty’s and Saez’s that relative mobility in America is basically immobile.

This is what is known as relative mobility, meaning, as the Economic Mobility Project conducted by the Pew Research Center, puts it, that “boats are changing places but says nothing about the strength of the ride.” Pew’s survey corroborates Chetty’s and Saez’s that relative mobility in America is basically immobile.

Seventy percent of those born into the lowest income bracket have remained in that bracket, 26 percent rose to middle or upper-middle class, and only four percent climbed to the top bracket. Unless you assume that virtually all poor people are poor because they are lazy and shiftless – a Social Darwinist argument, by the way, that you frequently hear on the right – their hard work doesn’t count for very much.

And there’s more. For all those who bellow about American exceptionalism and this being the only country in the world where one can pull himself or herself up by his or her bootstraps, only two countries – Italy and Great Britain – have less relative mobility than the United States, according to a 2013 study by the Russell Sage Foundation. Indeed, Denmark has three times the relative mobility of the U.S. And here is one more sobering fact from the study: Pakistan has almost identical mobility to the United States. But you don’t hear anybody trumpeting the Pakistani Dream.

That is relative mobility. There is also absolute mobility, which, as Pew states it, “refers to a dynamic in which a rising tide is lifting all boats, but it does not capture the likelihood that boats are changing places in the harbor.” In other words: Are you materially better off than your parents were? Again, looking at the Economic Mobility Project, Pew answers no.

Using data over four generations of the incomes of men in their 30s and adjusting for inflation, Pew found that “absolute mobility is declining for a significant group of Americans.” And this is a recent phenomenon. Comparing men aged 30-39 in 1964 with a similar cohort in 1994, there was little difference in income – a five percent increase over the 30-year period. Comparing the same age cohort from 1974-2004 tells a different and sadder story. The younger group had 12 percent less income than their fathers’ generation. That wasn’t supposed to be the bargain.

Absolute mobility is related to relative mobility in this sense. According to Pew, the greater the economic inequality in a society, the greater the likelihood that children will not be able to rise above their economic birth quintile. Former Council of Economic Advisors head Alan Krueger has called it “The Gatsby Curve,” after Fitzgerald’s hero, meaning greater inequality leads inexorably to greater immobility. And that is where income inequality comes in.

The great unhinging

Income inequality is a hot topic today, and for good reason. The differential between the top earners and the rest of society is greater than it has been at any time since the 1920s. Between the late 1940s and the early 1970s, incomes rose at almost exactly the same level across all the quintiles – richest to poorest. All nearly doubled. And then came the great unhinging.

Income inequality is a hot topic today, and for good reason. The differential between the top earners and the rest of society is greater than it has been at any time since the 1920s. Between the late 1940s and the early 1970s, incomes rose at almost exactly the same level across all the quintiles – richest to poorest. All nearly doubled. And then came the great unhinging.

According to the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, a left-wing think tank, the income gap began widening into a chasm. From 1979-2007 average after-tax income from the top one percent earners quadrupled while the bottom quintile increased 44 percent and the middle three quintiles 42 percent. Just to get that straight, that famous top “one percent” of Occupy fame earned 314 percent more while the lower 80 percent earned roughly 40 percent more. (For what it’s worth, by 2011, the recession had lopped 100 percent off the increase in the top one percent’s earnings since 1979, which was more than its effect on the bottom 80, though the gains were still five to one.)

Seen in another and even more terrifying way, in 2010, 23 percent of before-tax income belonged to the top one percent of earners and 17 percent to the top .5 percent. Yet another way to examine income disparity is to compare the income of CEOs to that of the average American worker. In 1965, the ratio of CEO income to worker income was 20:1. In 1978, that ratio had increased to nearly 30:1. By 2013, by one measure, it was nearly 300:1, and, lest anyone think this was economically justified, compensation was double stock market growth from 1978-2013. By comparison, the ratio of CEO income to worker income was 11:1 in Japan, 12:1 in Germany, 15:1 in France, and 20:1 in Canada.

Remember, that is for incomes. The picture is worse, 10 times worse, when one examines wealth – not how much one earns a year but how much one has accrued over the years. From the 1930s through the 1970s, thanks in part to unions and taxing policy, the vast differential in wealth that had previously existed between the richest and the rest of Americans gradually closed. By 1970, the richest .1 percent Americans owned seven percent of the country’s wealth. And then the gap opened again, widely, yawningly, until we were right back where we were in the 1920s. By 2012, they owned 22 percent.

Remember, that is for incomes. The picture is worse, 10 times worse, when one examines wealth – not how much one earns a year but how much one has accrued over the years. From the 1930s through the 1970s, thanks in part to unions and taxing policy, the vast differential in wealth that had previously existed between the richest and the rest of Americans gradually closed. By 1970, the richest .1 percent Americans owned seven percent of the country’s wealth. And then the gap opened again, widely, yawningly, until we were right back where we were in the 1920s. By 2012, they owned 22 percent.

In a study by the aforesaid economist Saez and Gabriel Zucman, the wealthiest 160,000 families in America own as much as the 145 million poorest families. By one measure, the Walton family, which owns WalMart, alone possesses as much wealth as the poorest 41.5 percent of American families. Just think of that: the six richest Waltons have as much wealth as the poorest 41.5 percent of American families.

Fall into the gap

But as the Harvard political scientist, Robert Putnam, told Der Spiegel magazine, the real basis of the dream isn’t the income or wealth differentials we wind up with. It is the opportunity we begin with.

“The fundamental bargain, the core of America,” he said, “has always been that we can live with big gaps between rich and poor so long as there is also equality of opportunity.”

So the real question for the American Dream is: Do poor and middle-class Americans have the chance to better their circumstances?

All of which brings us back to education, which may be the one force in American life that has the potential to be an equalizer, with the emphasis on potential.

All of which brings us back to education, which may be the one force in American life that has the potential to be an equalizer, with the emphasis on potential.

First, you have to get poor young people into the classroom. As New York Times columnist Nicholas Kristof reported, today there are more young American men who have less education than their parents (29 percent) than there are young American men who have more (20 percent), and only five percent of those whose parents failed to get a high school diploma finish college.

Moreover, a recent study by Penn and the Pell Institute for the Study of Opportunity in Higher Learning found that 77 percent of those students from families in the top quartile received a degree by age 24, while in the bottom quartile the number was only nine percent. So even if you can get a student to the classroom, you can’t make him graduate.

According to the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), the U.S. upper secondary graduation rate is below the OECD average – which is to say below the rates of virtually every industrialized country. And among 25-34-year-olds, America ranks 12th among the percentage of the population with a college degree.

Degrees of separation

So even though America boasts the finest universities and colleges in the world, this has had to date very little relevance for the American Dream for the simple reason that the inequalities in the larger society are likely to be replicated in the academic one. The richer you are, the more likely it is that a college education will raise your income. Again citing the Pew Economic Mobility Project, rich children without a college degree are still 2.5 times more likely to end up with incomes in the highest quintile as poor students who graduate from college. (Let’s face it: Rich parents make the best welfare state for their children.)There is only a 10-percent chance that a poor college grad will end up in the top income quintile, which is only two percent better than those who didn’t go to college. The comparable number for those born in the top quintile who get a college degree is 51 percent.

In large part, this is because poor students typically do not get to go to the best and most selective schools, like U-M, which are the most likely routes to graduation, much less high incomes and wealth. Only 34 percent of high-achieving, low-income students, as measured by grades and test scores, according to a 2013 study by economists Caroline M. Hoxby of Stanford and Christopher Avery of Harvard, attend one of the 238 most selective colleges in America compared to 78 percent of high-achieving, high-income students.

By one, albeit hotly disputed study of higher education in California, college actually resulted in a net transfer from low-income families to high-income ones. As Nicholas Kristof recently put it, “In effect, the United States has become 19th-century Britain: We provide superb education for the elites, but we falter at mass education.”

Dream a little dream

U-M, like many universities, is certainly aware of this, and the administration is trying to do something about it. Our own President Mark Schlissel has talked about exploring linking tuition to family income, promising to broaden outreach to poorer schools, and pursuing ways of providing sufficient financial aid to needy students. Many top-ranked schools are now doing the last of these, affording poor students a virtually free college education. But as important as it is, that may not be enough to attract students, many of whom lack knowledge of these programs and the self-confidence to apply to them. And it may not be enough to make any more than a dent in the inequalities that deny the dream to most Americans, especially when some studies indicate the demand for college-educated workers could actually be declining.

But there is another way in which U-M and other great universities can make a difference in revitalizing the dream. This one gets me back to my old professor, the intellectual and cultural historian Robert Sklar, who made me think about the dream, and to one of the most powerful functions of a university, which is to inform the national conversation. Through public outreach, universities can begin to change our discourse by helping to recontextualize the dream, rethink it, and take the onus off individuals and put it back on the system where it belongs. There is precedent for this in U-M’s teach-ins on Vietnam that helped move the discourse on that war and in the University’s role in the debate on affirmative action.This isn’t likely to pay any rapid dividends; the pace of mind-changing is usually glacial. But it is important nonetheless in removing self-blame. Only when hard-working Americans begin to question why their wages are stagnant and their children are stuck in the same economic rut as they are, will they begin to campaign for policies that may lead to greater equalization and mobility, including education.

This is why it is important that the University engages in helping to frame a national debate about the dream on which this country is predicated: Transforming economic failure into personal failure is a pernicious, life-sapping idea, a rich person’s idea, and it is factually wrong as well.

The truth is that just as people seldom succeed on their own, people seldom fail on their own. Each of us lives within circumstances larger than ourselves – most obviously the economic status of our parents. Even if you question the statistics about mobility, we all know people who work very hard, some two or three jobs, and still can’t make ends meet — much less achieve the dream with its $130,000 price tag. In fact, one could make a good case that the people who work the hardest in America are the ones rewarded the least.

So even as the University leverages mobility for poor students through education, it should also educate the larger public as scholars and intellectuals once did. We had a dream. It is gone. But we can regain if we understand how we lost it. In part, that is our University’s job.

Merry Clark - 1989

In essence, this matter is at the heart of my book, “Stripping Down to the Bones”, which paints a picture of how even a seemingly somewhat advantaged woman can still have a very hard time “making it” in America.

Reply

lewis(Bill) Dickens - 1964 Bachelor of Architecture

Wow, was that ever wordy! Was anything said?

As an architect who carried my school flag (A&D) and read the Great Society speech at commencement over LBJ’s shoulder, I’m quite sure that my Dream for America is extremely different than yours.

The University featured me, among others, during the 50th anniversary of the Peace Corps speech. Clearly, our current National President would not even exist were it not for Tom Hayden’s irascible persistence at getting some answers out of the political candidates.

Yet this past year the University seemed ashamed to mention the Great Society speech. And in the past 15 years Black student enrollment has declined by 50%.

So instead of the War on Poverty we got the War on the Poor and the Contract on the Middle Class.

On several occasions I wrote to President Mary Sue Coleman. In one letter I suggested the University ought to step up for Detroit and place a center right in the heart of the city. Surprisingly, a little office space was rented up by WSU. And on another occasion I mentioned that one local commentator who ran around with a Block-M varsity jacket was expressing opinions that really didn’t represent an educated perspective. And it wasn’t long before he thankfully stepped back.

Now the University missed the great opportunity to pick up a magnificent building downtown, before Dan Gilbert paid heed to Toby Barlow’s letter in the Huffington Post, to set up a branch that everyone could reach with any sort of transportation. But it has begun to assert itself and I just learned that it is developing influence in the Detroit School of the Arts, and it has brilliantly set up through Dean Monica Ponce de Leon, an Architectural Center that will serve three high schools with courses in architecture and — Oh my god, of all things — teach drafting because you have to, if you wish to teach Architecture.

Clearly it has been the Education schools with their philosophical nonsense that have destroyed the lives of at least three generations with their “new” math and their eschewing of rote memory, destroying commercial curricula, and placing students into an atmosphere of vapid irrelevance.

It really is no wonder why pants are being worn down just above the knees, which is a prison-style code expression of “I am taken and protected.”

Couple that with the ever-present cost-cutting drive for advancing technology where fewer and fewer are needed to make a product, and we see the great benefit of advancing technology heading us in the direction of no one being needed and everyone achieving the status of marginal to no utility with blather and bafflegab and inanity prevailing.

Is America getting more beautiful, more convenient, more kind, more happy, and more intelligent?

In some ways yes, again thanks to the Peace Corps and the ’70s and Detroit. And in some ways no. with some very pathetic, retrogressive attitudes as exhibited especially by one political party.

So what good is a college education if it advocates the destruction of commercial subjects, such as Architecture, Engineering, and Dentistry, Mechanical Drawing and Trigonometry?

We have seen the product of the Law School and their appointed and elected “officials” in destroying and carpetbagging Detroit with all of the precious historic engineering records lying now in a heap in a storage yard on the west side of town.

Governor Snyder should be ashamed of himself. Is he? No. Like Tyler Perry’s Jim Cryer, He’s going to run for higher office.

Only lawyers would have the arrogance of thinking that everything but “the Law” is irrelevant, just as the educators would think that it was the parents’ responsibility to properly educate their children and teach them their math facts, certainly not theirs because “We teach them how to think!” As told to me by one of my Daughter’s Teachers. So with Kumon and Eton Academy and an awful lot of driving to correct that, we are near destitute along with the disgust about the smears against the Blacks. Thanks Ed Schools! Nothing but blather, and inanities and irrelevance.

Bill Dickens

Architect ’64

Reply

Deborah Holdship

Bill — FYI per your reference to the “Great Society” speech by LBJ: Michigan Today did do a story about his commencement speech in 1964 when he first presented many of those ideas. See: http://michigantoday.umichsites.org/a8273/

Reply

Ann Oblesmith - 1994

What one neglects to consider in such an account is the ever-shifting denition of the “American Dream”. When did the American Dream become a $275,000 home and an SUV? Soldiers coming back from WWII were thrilled to have a little 2 or maybe 3 bedroom home with – wonder of wonders – electricity, heat, and running water. The lucky had a single-car garage, too. As more people achieved that dream, the dream shifted to bigger houses, more and bigger cars, etc. Now people consider themselves poor if they don’t have central AC and cable TV. Dreams are something on the edge of reachability, or they wouldn’t be considered dreams.

Reply

Robert Sherman - 1966

The American Dream has traditionally meant improving the lot of our children. Immigrants worked hard at menial jobs, saving their money so that their children could achieve through education. Those same immigrants could not achieve that dream today because the rate of increase in education cost has been extreme.

Today those below the poverty level are provided AC, cable TV, and expensive IPhones. But they cannot afford a university education, nor is education included in their aspirations. They are modern day slaves, serving their masters with their votes.

Reply

J Steve Kline - 1974, 1976

Thank you for the long and thoughtful article. I think the answer to your question is engraved on Angell Hall: “Religion, morality, and knowledge, being necessary to good government and the happiness of mankind, schools and the means of education shall forever be encouraged.” (Northwest Ordinance, 1787)

The founders of our nation knew that all men are created equal and that our rights come from our Creator. Those founders created a government with limited powers so that each person could pursue their dreams in freedom. No other nation was founded in this way. No other nation has a Constitution that so strongly limits government power. Those are the things that make America exceptional. Over the years, the national government’s power has expanded past the Constitution’s limits while, during that same time period, realizing the “America dream” has become less and less possible for many. That is not a coincidence. Weakening our Constitution makes it harder for individuals to fulfill their dreams. Our Declaration of Independence and Constitution were, and are, very real. They are also very radical. They are not dreams. They are the frameworks that allow Americans to pursue their dreams. The people who wrote the Northwest Ordinance knew what makes America exceptional, as did the founders of the University of Michigan and UM President Angell (I am one of his distant relatives).

UM can make a difference. It can admit the best and the brightest. It can teach them religion, morality and knowledge, and before they leave Ann Arbor it can make sure they have heard what makes America exceptional.

Oh—and beating Ohio State may not be part of the answer, but let’s not take a chance. Go Blue!

Reply

Robert Sherman - 1966

One ingredient is missing in this discussion of “Can U-M save the American Dream”: The University has taken advantage of the government student loans by severely increasing the cost of attending. The students must bear the burden of unbelievably high tuitions.

I paid all of my own expenses at U-M in the 1960s. If a student was to do that today, he/she would need to have an income during the summer break which is higher than the average American wage.

If U-M was to contribute by educating more students, including low income, professors and administrators would need to accept lower income. I don’t believe that will ever happen.

Reply

Herb Bowie - 1973

Nice piece, Neal! As a prestigious yet public institution, and one with an increasingly international student population, I agree that U-M could play a unique and valuable role in revitalizing our society’s hopes and aspirations. I think one of the questions for us is how to carve out a niche for public discourse that goes beyond the typically narrow and specialized concerns of academia, and yet avoids the trap of becoming part of the media circus that seems to suck all meaning out of our language.

Reply

Brenda Gitter - 1979

Excellent article that pulls everything together and Walmart just raised hourly wages to $9/hour. My three children have left the nest or are in the process of leaving. My eldest graduated from Michigan and is currently in graduate school. Even though it meant paying out of state tuition, we did it for the quality of education she received at Michigan. My loving maternal grandfather migrated with a seventh grade education from Tennessee in 1936 to work in the auto plants of Detroit. He quickly became a life member of the UAW and retired with a pension and healthcare. My father, also a 1962 Michigan graduate, was a public school teacher and an officer of the teacher’s union. Currently I live in a state which is a “right to work” and red state while a week doesn’t go by that workers don’t die from workplace injuries. For students from lower income families to succeed at the University level, they need support from their family and community and I mean more than financial support. Unions were influential in improving the opportunities for the middle class. As union membership has declined, CEO salaries have increased dramatically. Unions were collective voices for the American workers and they need those voices now. Political races are now who can spend the most. The University of Michigan raised my awareness of our societal problems as it did for my daughter. The problem is that we don’t have much time left to help the American worker and save the middle class. This message must be disseminated to all and education is just one piece, a major one, of the puzzle.

Reply

G.M. Freeman - 1950

I’m a child of the Depression. Never was there even an inkling that my parents’ generation was on a guilt trip because of the Great Depression.

I agree the article was wordy. Maybe the author didn’t have a hi school English teacher who taught writing a précis as I did.

U of M’s emphasis on political correctness such as banning certain words and expressions subjects the U to ridicule. 125

Reply