It never gets old

My guess is that most cineastes have at least one cult movie they enjoy revisiting time and again, even if it sometimes means going to theaters way past one’s bedtime.

What exactly is a cult film? I like the definition given in the Oxford University Press reference guide A Dictionary of Film Studies (2012). It’s concise and it considers the socio-cultural conditions that have distinguished the cult film phenomenon.

“Cult films,” the dictionary states, “denote an eclectic group of films defined post hoc in terms of their consumption by dedicated and devoted groups of filmgoers who engage in repeat viewing, celebratory enthusiasm, and performative interaction (memorizing dialogue, practicing gestures, wearing costumes, etc.) . . . Cult films are usually regarded as transgressive and/or oppositional to mainstream taste.”

That definition would fit very well with the classic cult film Rocky Horror Picture Show (1975), especially with regard to the behavioristic tendencies of devoted filmgoers. In addition, cult films may be perennial favorites simply because of their off-the-wall characters and quirky plots, e.g., Harold and Maude (1971), Pink Flamingos (1972), and The Big Lebowski (1998).

Cult films fall into several familiar categories. Truly bad genre movies: Bride of the Monster (1955) and almost any film directed by Ed Wood, for example. In the excessive melodrama camp we have Mommie Dearest (1981). As for movies with taboo/sexual content, you have Reefer Madness (1936) and My Own Private Idaho (1991). And there’s always Trainspotting (1996) for fans of drug-infused cinema.

The ultimate cult classic?

Then there is the cult film with such unique appeal that its legion fan base grows in explosive numbers with the passage of time. One such revered film is Ridley Scott’s futuristic take on life in the chaotic dystopian megapolis of Los Angeles, Blade Runner.That film was released first in 1982 to lukewarm critical responses and box-office reception. It was re-released in a director’s cut in 1992 and then came out as a final director’s cut in 2007. The latter, a 25th-anniversary edition, has enjoyed a cult response beyond phenomenal in its new international re-release this year. For the completist, the 2012 30th-anniversary Blu-ray release contains the different versions of the film, as well as a disc with more than a thousand production sketches and stills.

Last month the British Film Institute’s National Film Theatre programmed 49 packed-house screenings of Blade Runner: The Final Cut. Meanwhile the film was showing in non-indie venues throughout the city.

There’s a reason for this

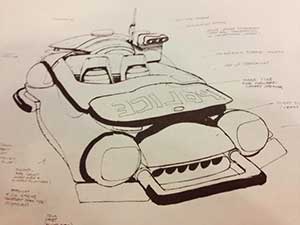

“The Blade Runner Sketchbook” (1982) by David Scroggy includes this design by Syd Mead of the flying police car. See larger image.

Back in the mid-’80s I first became aware that Scott’s movie was destined for cult status. On arriving at the home of friends for a Sunday afternoon get-together, I was told by our hostess that “the guys” were in the family room enjoying their annual viewing of Blade Runner. I joined them. I could see as we watched the film together why it held such strong appeal.

First there’s the remarkable production design for a film that is set in 2019 — 40 years beyond its conceptualization by Ridley Scott in 1980. Scott was determined to create an authentic futuristic metropolis that he described as “rich, colorful, noisy, gritty, full of textures, and teeming with life — much like a major city of today — a tangible future, not too exotic to be believed.”

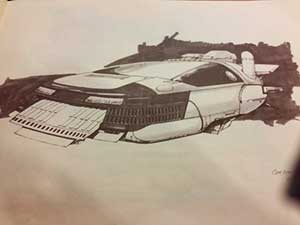

Legendary industrial designer Syd Mead, known for his ability to envision the future, sketched designs that would cover the architecture, technology, transportation, and fashion of an authentic 2019 landscape. The realization of that imagined world on screen resonates with pure genius.

Genre jumping

There’s also the broad trans-genre scope of Blade Runner, due to a script loosely developed from Philip K. Dick’s 1968 sci-fi novel, Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?

Up front the film adaptation is a post-apocalyptic tale about a group of off-world androids (“replicants”) who illegally return to Earth for urgent revenge against their Nexus 6 creators. Their programmed “lifetimes” are about to expire.

The plot’s dramatic arcs underscore a detective procedural, as ex-blade runner (“bounty hunter”) Rick Deckard (Harrison Ford) is summoned back into duty to track down and destroy (“retire”) the dreaded replicants. The action sequences are visually empowered by designer Mead’s futuristic police vehicles and flying transports, appropriately labeled “spinners.”

Exterior landscapes and surreal interior settings are brilliantly created with matte paintings, miniature sets and models, and atmospheric lighting overlays — well before the explosive magic of computer-generated imagery overtook science-fiction filmmaking. The nerve-shredding search-and-destroy scenes are a wonderful display of older-era filmmaking techniques at their finest, although the later editions include some advanced fine-tuning of imagery, sound, and music. One major sound edit in the later editions is the deletion of Deckard’s noir-styled voice-overs that are heard in the 1982 theatrical trailer above.

To further enhance Blade Runner’s broad appeal, the plot delivers a “love interest” for Deckard in the form of Rachael. Their scenes are underscored by the electronic synth compositions of Greek composer Vangelis. The symbiotic interplay between Vangelis’ music and the romantic pas de deux between Deckard and Rachael is pure, cinematic magic.

When I saw the film again in London last month at the British Film Institute it was nothing short of celebratory pleasure to be among 500 totally enraptured devotees, all of us there to re-enjoy a cherished film.

Presidential seal of approval

Former U-M president Jim Duderstadt is one of the film’s long-time devotees.

See a larger image of Syd Mead’s ‘spinner’ design, featured in David Scroggy’s 1982 book “The Blade Runner Sketchbook.”

“Blade Runner has long been one of my favorite movies,” he emailed me in April 2015, “in large part because I’ve been a Philip K. Dick fan since my teen years, but perhaps even more so because of Ridley Scott’s imagination in the design of a noir film for a distant future.

“The haunting atmosphere of the settings, the music of Vangelis, and the characters (particularly Harrison Ford as the ‘Bogart’ character and Sean Young as the replicant girlfriend) all merge together into quite an exceptional experience.

“And although the plot has shifted around from version to version (particularly the ending),” Duderstadt concludes, “the mood established by the film is more engaging than the plot itself.”

John Farrin - LSA '69

Thank You! I feel better about myself. I think I have every VHS and DVD version, and was thrilled to be able to Amazon the 5-disc Blueray edition. I even got my girlfriend to watch differing versions, although I suspect she may have been under duress. My kids were less forgiving in years past. Maybe I should share my pleasure with the Denver UM Alumni club as an annual showing on my 10 foot projection screen…? O.K. I also confess to attending the after midnight showings at the Ogden on Colfax of Rocky Horror Picture Show, including shouting the lines and singing the lyrics, but that was many years ago….

Reply

Tim Artist - 1979 & 1981

Enjoyed your write-up Frank! Been a fan of Blade Runner for a long time and of the Philip K. Dick novels that I read years before the movie. I’ll add one of my favorites, 1945’s “Detour” to the list of great cult films.

Reply

Joshua Rabinowitz

Fun article! I think another aspect to this film that has helped its cult status is the series of versions that have cropped up every decade or so. Early in 1991, when I was an undergraduate at UCLA, I had the opportunity to attend a screening of the long-rumored director’s cut of “Blade Runner” at the L.A. County Museum of Art. However, once the reels started moving, it was apparent to everyone there that this was not the director’s cut, but rather, a work print. Not what we were expecting, but an interesting viewing nonetheless!

Reply

Joseph Rauscher - 1966

Yes, the movie has held up very well – better than I have too! And I am very surprised that there was never a sequel.

Reply

James Duderstadt

Good article. (I didn’t mention my other cult movie … Ferris Beuller’s Day Off…)

Reply