The power of a pen, 1961

In the middle of the 20th century, the U-M historian Dwight Lowell Dumond was one of the country’s leading authorities on slavery, especially the long campaign to rid the U.S. of its “peculiar institution.”

Dumond was an Ohioan with a warm and courtly manner but no reluctance to express fierce opinions on national affairs. His research had cast new light into the dark corners of commerce in human beings. Some of his historical findings were even cited in the landmark 1954 school desegregation case, Brown v. Board of Education.

Year by year in the 1950s, Dumond searched southern libraries and musty archives for materials that would inform his masterwork, Antislavery: The Crusade For Freedom in America.

Connections between past and present were all around. As Dumond made his notes on old records of slave sales and the diaries of forgotten abolitionists, modern-day protesters were marching to safeguard the civil rights of African-Americans, and the nation was preparing for the centennial of the Civil War, the conflict that finally had broken slavery’s back.

Stain and triumph

Dumond regarded slavery as the great stain on America’s story and abolition as a triumph. But he was keenly aware, as he wrote in his preface, that when slavery was gone, “the white population of many sections, clinging tenaciously to the belief in racial inequality, soon reduced . . . freed Negroes . . . to a second-class citizenship, which is and always has been a modified form of slavery from colonial times to the present.”

By 1960, he was fine-tuning a thick manuscript of 44 chapters for publication by the University of Michigan Press. Dumond told colleagues the book would lose him every friend he had ever made south of the Mason-Dixon line, even among his fellow historians.

By 1961, with the Civil War centennial underway, editors at U-M Press believed they might have a bestseller in Dumond’s Antislavery. To give it a strong start, they prepared a vigorous marketing campaign.

“One of the most important studies”

First the publisher sent advance copies to famous writers and historians. Back came testimonials for the dust jacket and advertisements.

First the publisher sent advance copies to famous writers and historians. Back came testimonials for the dust jacket and advertisements.

Poet and Lincoln biographer Carl Sandburg said the book was “one of the most important studies ever made of the rise and fall of chattel slavery in the United States.” Civil War authority Bruce Catton said, “Dumond candidly talks about slavery for what it was — an everlasting moral wrong which crippled American democracy for half a century and which finally had to be erased by means of the costliest war we ever fought.” An official of the N.A.A.C.P. wrote a personal note to Dumond saying: “We count you as one of the genuinely solid champions of freedom.”

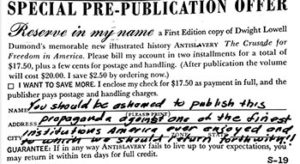

U-M Press prepared a brochure offering a special first edition at a discount. The brochure was illustrated with drawings of enslaved black children and advertisements for slave auctions. Even the envelope was printed with a facsimile of an old auction poster: “Negroes for Sale!”

It’s not clear how many copies of the brochure that U-M Press sent out. But they went all over the country. And they were noticed.

Poison ink

Orders for the book flowed in. But so did a tide of poison ink. Dumond and the editors at U-M Press now found out just how raw was the racist outrage of white Americans offended by the civil rights movement.

Their anger was so intense that even a book covering historical events of a century ago seemed a direct affront to their cherished belief in the inequality of blacks and whites.

Ugly messages to the author and publisher came from all over the U.S. — many from the South but plenty from the east and west coasts and Michigan itself. Most were scribbled on the original order forms.

“Has U-M gone ‘Commie’?”

A sample of Dumond’s hate mail. See a larger version. (Image courtesy of U-M’s Bentley Historical Library.)

Some respondents warned the book would ignite violence:

“Do not sell this book. It is too degrading and will start a civil war.”

“I think it a shame to stir up more hate between the races by publishing such a book.”

Many suspected Antislavery was a tool of Soviet propaganda:

“Has the good old U. of M. of bygone days gone all-out ‘Commie’?”

“This looks like an attempt to create disorder and confusion. Was this printed and financed by the Communists?”

And some messages consisted of simple, undiluted hatred:

“You should be ashamed to publish this propaganda against one of the finest institutions America ever enjoyed and to which we should return forthwith!”

“I still believe slavery is the only solution for the n——.”

Dumond’s response

Professor Dumond preserved many of these messages in his personal papers, now stored at U-M’s Bentley Historical Library. None of his surviving letters contain his reflections on this encounter with poison penmanship.

But if his detractors had meant to intimidate him, they were disappointed. Before and after his retirement in 1964 (after 33 years of teaching, with some 16,000 students in his grade books) Dumond spoke often — and with no reservations — about the meaning of racial injustice as the nation reflected on the legacy of the Civil War.

Some historians criticized Dumond for taking a moral stance in his writings. They preferred the moral distancing of an “objective” chronicle of the past.

But Dumond rejected that claim, and when he gave public addresses around the country, he did not stop at condemnation of slavery itself.

“No certain peace”

A hundred years after the Civil War, students continued to fight for civil rights, often by staging sit-ins. (Image courtesy of U-M’s Bentley Historical Library.)

Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation and the Thirteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution had ended slavery as an institution, he said. But “emancipation did not disassemble the psychological basis of slavery. Slavery was something more than the legal bondage of 3.5 million people. It was a firm, almost universal belief among the whites of the rebellious areas, and far too many elsewhere, that the Negroes were biologically inferior to themselves.

“Until every person feels the injuries and cruelty inflicted upon another as keenly as if it were inflicted upon himself, until all men understand that in denying equality to others . . . they are defying not only the Supreme Court but the Supreme Ruler of the Universe. Until we start thinking in terms of human hopes and human happiness, about character and intelligence instead of color, there will be no justice and no certain peace.”

Dumond continued to write and speak about American history until his death on May 30, 1976.

Sources include the papers of Dwight Lowell Dumond, Bentley Historical Library; Sidney Fine, “Memorial: Dwight Lowell Dumond,” LSA Minutes http://tiny.cc/zcyqjy); and Dwight Lowell Dumond, Antislavery: The Crusade for Freedom in America (1961).

The top image, from the National Maritime Museum, served as the background cover art for Dumond’s book. It is captioned “The African slave trade — slaves taken from a dhow captured by H.M.S. ‘Undine'”

Elizabeth Johnson - 1980 and1984

I am pleased and proud to learn of this professor and his work. As a white person who grew up in the era of civil rights I am proud of the heroic spirit of this professor and his publisher. This could be an inspiring story if put forward as a movie. Similar to the current “Hidden Figures.” Who will write and film it? University of Michigan???

Reply

Rex Hauser - 1978,1980,1988

I realize, Elizabeth, that Ken Burns (Ann Arbor Pioneer High, 1971 or 1972) has a backlog of over ten years on projects that he would like to accomplish. He’s not the only filmmaker out there (but surely there may be folks who came out of the making of “Eyes on the Prize,” who might be interested). I would hope that the story will include the work and activism that went toward creation of the Center of African American Studies (hoping i have this right),and its leaders; also the internal struggle of UM, known as BAM in the early 70s, and continuing work (scholarship and activism) that honors the civil rights past and those who went before. Thank you.

Reply

Melon Dash - 1980

This story is important to me, not only as a source of information that helps explain where the country is today–still fighting the cold Civil War–but also as an observer of another well-loved institution that is bereft of value to the American public it supposedly serves that has never been caught. Knowing Dumond and UM stood up for what was right and handled the backlash helps me know it’s possible to survive and contribute to the forwarding of our culture by exposing the truth and sticking to it.

Reply

Mary Beth Norton - 1964

I took a course in Civil War history from Dumond near the end of his teaching career and have a copy of his book. I recall having heard that he lost many notes in the fire when Haven Hall burned in 1939 (? Date) and had to redo much of the research. Is that story true? If so, it truly shows his dedication to the topic. As a historian myself I long worried about losing notes. The ability to have multiple copies in multiple places because of computer files gives me great reassurance these days.

This story about the responses to his book is sobering, but of course it couldn’t have been written had Dumond, with his historian’s instincts, not saved them.

Reply

James Tobin - 1978, 1979, 1986

Dr. Norton: We just looked into it and found that some portion of Dumond’s papers were, indeed, among many materials lost in the Haven Hall fire of 1950, set by an arsonist.

James Tobin

(Readers of Michigan Today will be interested to know that Dr. Norton, an Ann Arbor native, is one of the most distinguished historians of her generation. She is the Mary Donlon Alger Professor of History at Cornell University. Her books include “Founding Mothers and Fathers” (1997), a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize.)

Reply

Kenneth "Ken" Peters - 1962 M.A and 1972 Ph.D

I am happy that Dr. Dwight L Dumond and his contributions are being broadcast through this brief but cogent article by James Tobin. As a graduate student in American history, I had the good fortune of having Dr. Dumond as a professor for a pro-seminar on the Civil War. Although our class learned a lot about that conflict, we also absorbed a great deal more from Dr. Dumond’ s incisive comments about the institution of American slavery and the various crusades against it. These comments motivated me to read and reread his epic book Anti-Slavery, which I still maintain is the best scholarly effort on the topic. I relied heavily on Dr. Dumond’ s work and comments when teaching U.S.history in Michigan and later when I was a professor at Benedict College, a predominantly African American institution, and at the University of South Carolina, where I was a faculty member for 33 years.

Reply

John Morgan - 1960 and 1962

I was fortunate enough to take Civil War history from Professor Dumond. Dwight Dumond was a great lecturer and I still remember many of the things learned in my short time in his class. During my time at Michigan the history department had so many great professors; it was a thrill to be a part.

Reply

Kevin Smith - 1978-1982

This story is very impactful. I am proud that such work on this topic arose from a professor at the University of Michigan. Dr. Dumond demonstrates through his work the conviction one can and should have when taking a stance for ‘right’ even when some around him objected.

The most meaningful quote from the article that is applicable even today is, ‘Until every person feels the injury and cruelty inflicted on others as if it were inflicted upon himself, until all men realize that by denying equality to other is not only going against the Supreme Court but also going against the Supreme Ruler of the Universe. Until we start thinking in terms of human hopes and human happiness, about character and intelligence instead of the color there will be no justice and no certain peace.”

These words speak volumes about why we still have not overcome our painful past in achieving equality and justice for all.

Reply

G.M. Freeman - AM 1950

How long must there be a constant drumbeat with respect to what some Americans engaged in decades ago? What is the motivation to insist on aggravating the racial divide?

“Today’s Blacks clearly benefitted from slavery. My wealth is far greater and I have far greater liberties than if my ancestors had remained in Africa. [Walter Williams, Economic Chair at George Mason University in VA as quoted in the 8 May 2000 US News & WR]”

Reply

Rex Hauser - 1978,1980,1988

M/Ms Freeman, Yes, there must be a constant drumbeat, as you so correctly assume in this regard. You may be tired of it, but I believe that with an in-depth education on matters of the cultures, spiritual impacts, and economics involved in that institution, you would not “put it all in the past,” as so many (even a majority, until recently) have desired to do. The past is very present. You might want to begin with what founding folks like Benjamin Franklin said (his 1790 spoof of slavery, while critiquing the enslavement of whites on the Barbary Coast). And please look at the Rev. David Rice statement to the Kentucky Constitutional Convention, 1792, outlining the psychological and other ravages of slavery! Much of that remains true, showing the ‘bedrock’ of racist belief. Too bad for all, but the early efforts of some of the country’s leaders did not prevail for many decades to come, after abolition and a horrible Civil War began to decide ‘the question.’ Thank you.

Reply

Karen Morse - MSI, 2003

I’d appreciate it if the author would share the citation for the “no certain peace” quote. Is it from _Antislavery_ or from the text of a speech that was found in his papers at the Bentley or … ?

Reply

John Myers - 1954 M.A., 1961 Ph.D

I was Dr. Dumond’s Graduate Assistant for 3 years in the mid-1950s for courses Sectionalism and Reform and Civil War and Reconstruction. Sitting through the same information three times was no problem as Dr. Dumond made it so interesting. A highlight each year was his lecture on Lincoln delivered on approximately Lincoln’s birthday. One page of Anti-Slavery was the result of my work in a seminar. He inspired me to do my dissertation with the theme of the 1830s antislavery agents. I have a copy of the book which Dr. Dumond gave me. My wife and I were entertained graciously in the Dumond home.

Reply

James Tobin - 1978, 1979, 1986

Ms. Morse — The quotation you asked about is from Dumond’s address at U-M’s observance of the centennial of the Emancipation Proclamation, 1/1/1962. He may have been quoted in the Daily and elsewhere close to home, but I found the quotation in a column in the Indianapolis Times dated 3/19/1963. If you’ll send me an email with your address, I’ll be happy to send you a digital copy of the column. tobinje@miamioh.edu

Reply

Karen Morse - MSI, 2003

Thank you so much, Mr. Tobin. I’ll email you today.

Reply

Charles and Susan Morton - 1955, 1957, 1958, 1969

Dwight and Irene Dumond were fond neighbors of ours on Morton Avenue in Ann Arbor in the 1960s. I never had a conversation with Dwight about slavery but he had strong opinions about many other subjects.

He said that he was hired by the University of Michigan in 1930 with a salary of $3000 and it increased $100 per year until it reached $4500 in 1945. No wonder he wrote books!

When he reached 70 years of age, he was forced to retire. He did not like that and said he could not afford to stop working. So, he contacted other universities and was hired for one year at Howard University and another year at Colgate University. We lost track of them when they moved.

Dwight and Irene were good people and good friends!

Reply