Cave man

I’ve just returned from Northern Spain and the Cave of Altamira. It ranks among the oldest of our discovered sites. The dating is approximate, since our ancestors lived there for thousands of years, and the Upper Paleolithic Period was a lengthy one. But somewhere between 35,000 BC and 11,000 BC, Altamira sheltered tribesmen who sought relief from the weather and safe haven from assault. Here they built their fires underneath the rock-vault; they cooked and ate and slept and honed their tools and tanned their hides and buried their young and old dead. Further, they made art.

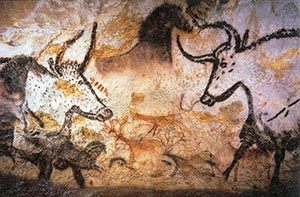

Long years previous, I visited Lascaux, in Southern France, and the two are collateral cousins. No doubt the painters were unrelated, and eons as well as miles intervene, but there’s an overarching similarity of atmosphere in the ancient stone galleries. They have the feel of temples, really, with polychrome walls and ceilings long before Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel or the work of Tintoretto in Venice or the murals of Diego Rivera in Detroit. The visitor still stands in awe of human ingenuity and the enduring power of the artistic impulse — color and form incised on rock since the seeming-beginning of time.

There are other cultures where much the same holds true. In India, Australia, Namibia — all over the globe, it would appear—Homo sapiens emblazoned figures on cave walls. They drew bison and horses and wild boar and goats, with protuberant bellies and horns. The fissures and bulges and hollows in rock form part of the bodies portrayed. The animal kingdom predominates here, though in distant countries a shaman or stick figure emerges from the outcroppings of stone.

Storied past

These shapes are colored red and black and brown, ochre, sienna, and white. How the artist or artists managed to take perspective into account — the rocks are irregular, often cracked — is a mystery among mysteries, and to imagine lying on your back in the deep dark of such a cave, then blowing pigment upwards is to beggar the imagination. This was mastery. We don’t fully understand the purpose of these images — whether they were hunting aids or emblems of some sort of worship, whether they were in essence descriptive or prescriptive: a way of showing what the tribesmen saw or wished to see. But the power of these renderings is undiminished, wholly present, and a first reaction to Altamira’s discovery (in 1879) was that this was modern art, a hoax.Once the caves were uncovered and entered anew, modernity did enter in. By this I mean the trickle and then stream and torrent of visitors, the bacteria on clothes and mud on shoes and the stale of tobacco, pollen, and hot, humid breath. In order to preserve the paintings from indiscriminate exposure, the governments of Spain and France (to take only the examples of Altamira and Lascaux) constructed replicas of the original caverns. Now, the visitor — unless particularly privileged and arranged for long in advance — must study imitations, not the thing itself. You join a line of fee-paying tourists and walk past display cases and maps. As the depth and dark accretes, you peer upwards at the colored rock and, dimly at first and then with increasing acuity, learn to identify shapes. Here’s a tusk and there’s a hoof, and see how the seam in the stone runs between them, suggesting a belly or back. Guides tell you what you’re looking at and hold out their hands for a tip.

Out of time

In Lascaux I’d felt shortchanged a little. It was as if the lack of authenticity had turned the wondrous place into a secondhand display. The installation felt commercial and the crowd was large. This is one paradox of democracy: common access to a place — think of Jones Beach or the gallery housing the Mona Lisa — robs it of its singularity. In Northern Spain, however, the same did not hold true.

There are many other caves in the area of Altamira; size and centrality suggest it was a meeting place. My wife and I were happy to take sanctuary in a hall that replicated the one first occupied by bands of tribesmen: 15 or 30 in a clan, and most of them short-lived. They would retreat for safety but congregate near the mouth of the cave, where there was light and air. The average life expectancy was less than 30 years; almost no one survived to 50, and women were — because of the dangers of child-bearing — doubly at risk of an early demise. Thomas Hobbes’ description of life as “nasty, brutish, and short” held true for Homo sapiens then, as it does, alas, for too many on the planet today.

But what a place! Pablo Picasso famously said, “After Altamira, everything is decadence.” What he meant, I think, is that art as play (or storytelling or ornamentation or self-expression or exploration or prophecy or homage) is in every case a sub-set of the original impulse: to render the world in color and shape so that we may take our place in it. And it matters not a whit if what we’re looking at is the original or its careful replica and modern imitation. I felt as moved in the presence of “false” Altamira as would have been the case, I think, had I gained entry to its ancient and authentic counterpart. We marvel now as then.

All this has set me to thinking: the child’s beloved comfort-blanket, the totemic carving, the religious relic, and the collector’s prized painting belong to the one category — an object imbued with reverence, a still-point in the turning world. For those of us who think of art as a necessity, the looming head of a wild boar or belly of a pregnant horse transforms a wet, cold, ancient cave into a sacred space.

Jerry Frank - January 1959

Thank you for sharing. Someone thousands of years past had the passion to create this picture and took the time from his or her short life to record this portion of his life. What enduring legacy can we leave to compare with this?

Reply

William Deubel - 1973

I doubt this art was in reaction to a lack to fill in a relationship to the world. Art is created not as a distinction of scale despite Picasso. The intrinsic value of art takes place in sufficient quantity when we respond to the surprise of the dominant reality we can only respond to. There is no expectation I believe of this becoming finished for a desired end that supposedly satisfies a need.

Reply

Denis Jacques - 1964

Thank you…I think this was my most interesting U of M article to date.

Reply