It was a very good year

The year 2018 delivered five remarkable nominees for the Academy Awards’ Best Foreign Language Film Oscar:

- Roma (Mexico;

- Shoplifters (Japan);

- Cold War (Poland),

- Capernaum (Lebanon);

- Never Look Away (Germany).

Each film is the work of a masterful, provocative director — four men and a woman. Cinematic diversity is on full display, along with unique storytelling. Roma and Cold War return to the silver-screen aesthetics of a black-and-white, light-and-shadow palette. Never Look Away and Cold War are period dramas set amid the political residue that endured in post-WWII Europe. And Capernaum offers an intense, empathetic treatment of a young boy’s survival struggles in contemporary Beirut. Although not all of the five nominees have yet to make their way into local movie theaters or streaming outlets, each deserves a visit.

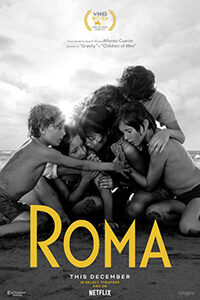

Roma

(Netflix, 2018.)

My February 2019 column “Aesthetics, appeals, and Alfonso” highlighted the innovative visual and thematic elements in Alfonso Cuarón’s memory-inspired Roma.

The semi-autobiographical Roma presented a humanistic study of family life in a Mexico City suburb in the 1970s, a time that coincided with political clashes on the city’s streets. Cuarón also created an endearing paean to his childhood nanny (Lido), called Cleo in the film. The 25-year-old indigenous Mexican actress, Yalitza Aparicio, makes a brilliant acting debut as Cleo.

In 2013, Cuarón won the Best Director Oscar for the technologically brilliant Gravity. Afterward, rather than accept another mainstream Hollywood project, Cuarón decided to return to his native Mexico and make Roma. He wrote, produced, directed, co-edited, and shot the film. That multi-tasking effort earned Cuarón dozens of international awards and citations. Its 10 Oscar nominations tied Ang Lee’s Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon (2000) for a non-English language film.

I concluded my Michigan Today review last month by saying I found Roma to be one of the most emotionally stirring and memorable motion pictures I’d ever seen. At this year’s Academy Awards presentation+ Cuarón won the Oscars for Best Director, Best Cinematography, and Best Foreign Language Film.

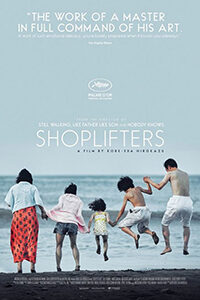

Shoplifters

(GAGA Pictures, 2018.)

Japanese director Hirokazu Kore-eda and Alfonso Cuarón are similar in many ways. They’re both in their mid-50s, and like Cuarón, Kore-eda is a seasoned filmmaker who has often written, produced, directed, and edited his own work. Stylistically, critics celebrate his films for their meditative and reflective pacing, qualities seen in Roma.

Shoplifters (or “shoplifting family” in Japanese) is Kore-eda’s eighth feature film and was Japan’s first Best Foreign Language Film nomination in 10 years. The screen drama is reminiscent of earlier work that explored poverty and family issues in contemporary Japan. Nobody Knows (2004) is a notable precursor to Shoplifters. That film follows four half-siblings between 5-12 years of age, each with a different father. The children occupy an apartment with their mother who often abandons them for long periods. The eldest, Alkira, assumes the role of family provider and is also left to deal with the fact that his three youngest siblings are living in the apartment illegally. They have to be kept hidden so “nobody knows.”

Shoplifters also presents a complex study of “family,” as discovered through a series of backstory character revelations. Poverty and survival in contemporary Tokyo are critical factors in Kore-eda’s ensemble drama, with seven characters ranging in age from 5 years old to 70-something. The characters share a small cramped living space and support one another through their efficient shoplifting for food and household provisions. The film opens with Osamu (Lily Franky) and 10-year-old Shota (Kairi Jyo) engaged in the smooth art of stealing. On their way home, the two come upon five-year-old Yuri (Miyu Sasaki), alone, cold and hungry.

The girls discover Yuri has been abused, and she soon endears herself to the “family.” She tags along with Shota and becomes a surrogate “daughter” to Osamu’s partner Nobuyo (Sakura Ando). Other characters are Aki (Mayu Matsuoka), a men’s-club hostess, and Hatsue (Kirin Kiki) an elderly matron, lovingly called“Grandma.” She holds the rent lease to the house. It becomes clear that the residents are a family of outcasts whom Grandma has created and accepted; she is fearful of dying alone.

Kore-eda’s fills his screen exploration of this ersatz family with direct and indirect implications. As Nobuyo draws closer to Yuri, she raises philosophical questions about the concept of family and parenting. She asks: ”Might it not be better for one to choose one’s family?” Later she challenges a social worker’s inquiry into Yuri’s illegal presence in the household. “A child born to a woman doesn’t make that woman a mother,” she argues. As Shoplifters moves toward a disrupting conclusion, Kore-eda leaves the viewer with much to ponder. The film was awarded the Palme d’Or at Cannes last year.

Cold War

(Kino Świat –Poland, 2018.)

Pawel Pawlikowski’s film spans 15 years beginning in postwar Poland in 1949 and ending in 1964. The tale spans the rocky course of an impassioned love affair between charismatic music director Wictor (Tomasz Cot) and vivacious singer-dancer Zula (Joanna Kulig). Pawlikowski’s parents inspired the central characters, and he dedicates the film to them.

Cold War begins as Wictor and a small crew traverse the Polish countryside seeking to record authentic music and restore some of the cultural traditions lost during the war. The director catches amateur musicians performing in documentary fashion.

Wictor and Zula meet during an audition for an international tour designed to highlight Polish folk music and dance. Wictor, the musical director, is captivated by the talented Zula’s natural beauty and “unique” energy. As their love affair unfolds, Zula becomes the music maestro’s star performer. But their relationship is tested as the troupe tours Warsaw, Berlin, Yugoslavia, and Paris. Cold War‘s on-again/off-again romance is played out almost entirely against a backdrop of song-and-dance numbers, alternating among folk music, regional dance routines, and night-club jazz.

Shot in black-and-white within a once standard 3:4 frame/aspect ratio, Pawlikowski revisits the stylistic techniques that earned him the 2015 Best Foreign Language Film Oscar for Ida. The reduced width-to-height format allows frame compositions that are visually restrained and intimate. Cinematographer Lukasz Zal gives as much attention to the sides and upper parts of an image as to what appears in center frame. Polish location cinematography is similar to that seen in Ida, with a deserted country road making its own stark conclusions.

Pawlikowski was awarded the Best Director Palme d’Or citation at Cannes.

Capernaum

(Mooz Films, 2018.)

Nadine Labaki’s compelling vision of life in one of the poorest neighborhoods of her native Beirut is uncompromising in what it reveals. One of Lebanon’s top actors, Labaki, spent three years researching material for Capernaum before co-writing the screenplay. Labaki cast the film using residents of the impoverished neighborhoods she had explored, and she encouraged them to draw on their own experiences as the film’s dramatic vignettes played out.

Zain, the principal protagonist, is portrayed by Zain Al Raffea, a Syrian boy who had been living with his refugee parents in Beirut for eight years. Having not been registered at birth and lacking other forms of official identification, Zain’s age is a bit of a mystery.

In Capernaum’s screenplay, Zain appears as a neglected, unloved urchin with a saucy tongue and plenty of street smarts. The film opens as a judge interrogates the child in a courtroom: “Why are you attacking your parents in court?” Zain brashly answers: “For giving me life!”

This and other visits to the courtroom appear in flashback, providing a frame for Zain’s life experiences. A critical scene involves the boy’s despair over what his parents are willing to do to survive economically. He reacts with fury but is unable to prevent his 13-year-old sister Sahar (Cedra Izam) from being to marry Assad (Nour el Husseini), the family’s lascivious landlord. So he packs a garbage bag of clothes and escapes on a voyage that reveals his determination and evolving character.

The boy takes a bus to an amusement park seeking work. There he meets Rahil (Yordanos Shiferaw), an Ethiopian immigrant working two jobs a day as a single mother caring for her baby son, Yanos. After Zain steps in to care for Yanos, Capernaum springs into unexpectedly tender and humorous life as the two boys charm one another and the audience. Through Rahil’s plight — her legal papers are expiring — common contemporary issues surface: separation of migrant children from parents, secretive incarceration of migrants, falsified documentation, and deportation. Capernaum, like Vittorio de Sica’s The Bicycle Thief (Bicycle Thieves, 1948) is a powerful vérité-styled, social-realist film that exposes the desperation of people trapped in inescapable life situations. Deeply poignant on all levels, it is also about a boy’s search for identity. When you see Capernaum, you’ll understand why at its conclusion it received a 15-minute standing ovation at Cannes. The judges awarded Capernaum its Grand Jury Prize.

Never Look Away

(Walt Disney Studios Motion Pictures, 2018.)

This German picture is the work of writer-director Florian Henckel von Donnersmarck whose 2006 masterpiece The Lives of Others received the Oscar for Best Foreign Language Film.

That picture begins in East Berlin in 1984 where the secret police (STASI) is pervasive. STASI Captain Gerd Miesler (Ulrich Muhle) bugs socialist playwright Georg Dreyman (Sebastian Koch) to record his conversations with his mistress, friends, and compatriots. The thematic blending of artistic integrity with political snooping led critics to declare The Lives of Others one of cinema’s greatest films.

Gerhard Richter, who is named Kurt Barnert in the screenplay, inspired Von Donnersmarck’s Never Look Away. Set in post-war East Berlin, the film opens in 1937 inside a Dresden art museum where an exhibit of “Degenerate Art” has been curated to impugn the works of famous abstract artists. Pre-teen Kurt (Cai Cohrs) and his aunt Elisabeth (Saskia Rosendahl) listen as a guide mocks Kandinsky, Picasso, and a host of others. Elisabeth whispers to Kurt that she prefers this art, and outside urges him to “Never look away. Everything that is truth holds beauty in it.” This charge impels young Kurt to avoid seeing Nazi-era atrocities by covering his eyes with a raised hand. But at one point he sees the Nazis forcibly take Elisabeth to be sterilized in a center for the mentally ill.

This and knowledge of Elisabeth’s ultimate fate initiates an odyssey that commands 188 minutes of screen time. Maybe some will find Never Look Away too long. I did not. First, the film offers a fascinating, up-close depiction of artistic creation and its many possibilities. As a young adult and would-be artist, Kurt struggles to discover the type of art he wishes to create. Ultimately, he escapes to West Germany and there wins admission to the Dusseldorf Art Academy known for its “anything goes” attitude. During these sequences Never Look Away captures art in progress from the moment the sketch pencil touches the canvas until the painting is fully realized. I was mesmerized.

In addition, a romance blooms between Kurt and fellow art student Ellie (Paula Beer). The girl’s father (Sebastian Koch), a former SS ob-gyn doctor with a secret Nazi-era past, adamantly opposes the affair, even after they marry.

Outstanding acting performances by Tom Schilling, Paula Beer, Saskia Rosendahl, and Sebastian Koch give life to richly dimensioned characters. The supporting cast is just as good: Ina Weisse, Oliver Masucci, and Hanno Koffler.

Kurt’s creative breakthrough and consequent critical success finally occur as his artistic metier comes through in photorealistic paintings taken from private snapshots and a startling front-page news photograph. One work has combined three black-and-white images into a single painting, discreetly blurred by vertical brush strokes — a creative technique employed by Gerhard Richter, the film’s source of inspiration. That painting, highly praised in an art gallery meet-and-greet, had elicited a more visceral reaction earlier in the film by a visitor to Kurt’s studio.

Kurt’s decision to merge life with art coalesces here with a concluding reference to Nazi Germany’s not yet fully resolved past. Never Look Away may not quite match the masterful The Lives of Others in moral and political potency, but it’s unforgettable storytelling and it’s generously entertaining.

Frank Legacki - 1961& 1964

My wife and I have seen four of these films – – Capernaum, Never Look Back, Cold War and Roma – – and each is outstanding. Very good films. We have not seen Shoplifters yet, but we will.

My favorite of the group is Carpernaum. This was is a powerful, compelling film, made more so by the fact none of the actors are professional actors. The young boy in the film is amazing.

FL

Reply