In justice

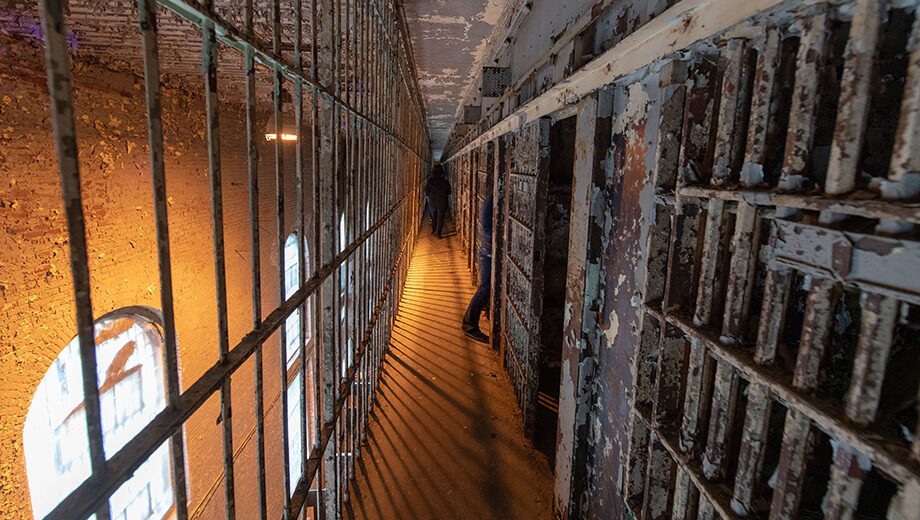

UM-Dearborn lecturer Aaron Kinzel (center) took his students to the Ohio State Reformatory, a former state prison in Mansfield, Ohio, that was used as the setting for the movie The Shawshank Redemption. (Photo: Roger Hart, Michigan Photography)

When Aaron Kinzel was 5 years old, his mother’s boyfriend used him to break into houses.

Kinzel would pop locks on windows and unlock doors for the older burglar.

It was just one of the many ways his childhood collided with the criminal world.

Looking back, Kinzel remembers bouncing between houses in Ohio and Michigan, and watching his mother’s boyfriends — some of whom spent time in prison and engaged in illegal firearms trade and drug dealing. He witnessed violence throughout his childhood, including when his stepfather attempted to murder him at age 8 by shooting at him while he fled the family home.

These experiences left a deep imprint on Kinzel, who later found himself imprisoned for almost a decade.

“The reason I tell these things is because a lot of people that are in the carceral state are traumatized,” says Kinzel, now a University of Michigan-Dearborn lecturer in criminology and criminal justice studies. “And that’s not to take away from their criminal activity or accountability for their behavior, but a lot of people were subjected to crazy stuff as kids. So they become that which they hate and that which they’re subjected to.”

At UM-Dearborn, Kinzel now uses his life story and personal experiences with incarceration to teach students about the criminal justice system.

By sharing anecdotes from his past, Kinzel combines theory and practice in the classroom, providing students a unique lens into a system that incarcerates approximately 2.2 million people in the United States.

Aligning with the University’s goals to enhance diversity, equity, and inclusion on campus, he says opening up to students also helps them feel comfortable enough to share their own stories of how incarceration has affected their families.

To further bring prison conditions to life, Kinzel also takes his students to carceral spaces.

Last semester, he took his students to the Ohio State Reformatory, a former state prison in Mansfield, Ohio, that was used as the setting for the movie The Shawshank Redemption. The prison first opened its doors in 1896 and closed in 1990.

Following footsteps

An entrance at the Ohio State Reformatory, a former prison in Mansfield, Ohio, where scenes from the movie “The Shawshank Redemption” were filmed. (Photo: Roger Hart, Michigan Photography)

During his teenage years, Kinzel continued the cycle of crime he witnessed throughout his childhood, and started selling drugs with his mother and her boyfriend. As a result, he spent time in juvenile detention facilities when he was 15 and 16 years old.

His first felony arrest came at the age of 17 for selling cocaine, and Kinzel eventually collided head-on with the criminal justice system when he and his girlfriend ran away together with a stolen car.

Police pulled the couple over, prompting a wave of panic in Kinzel, who was on probation and had a gun and drugs in his possession.

Once police officers pulled up on his left, Kinzel pulled out his gun and fired out his window. Within seconds, officers fired 15 rounds into the back of the vehicle. No one was injured in the incident.

After his arrest, Kinzel sat in county jail for a year and half, and received a 19-year prison sentence. He was released on parole in 2007.

Soon after, Kinzel quickly earned associate’s and bachelor’s degrees with honors but still struggled with employment due to his felony convictions. He later earned a master’s degree from UM-Dearborn and currently is finishing a doctorate at the same institution.Now-retired Washtenaw County Circuit Judge Donald Shelton, who also serves as director of the UM-Dearborn criminal justice program, recruited Kinzel to teach at the campus.

At UM-Dearborn, Kinzel shares his personal stories with students depending on the lesson, such as the experience of spending about three years in solitary confinement.

It’s an approach that combines theoretical frameworks with a practical lens, Kinzel says.

“When students see someone like myself who’s an academic, who has a higher credential and is more of a down-to-earth, likable person, it helps humanize carceral populations,” he says.

“I think experiential learning is the most powerful way to grasp knowledge. So when I take them to these spaces and they end up talking to me and other people who have been in the system, it really creates everything in this real-life context. They’re kind of living it themselves as opposed to just reading from a book.”

Being there

During his recent trip to the Ohio State Reformatory, Kinzel and students from his criminology classes walked through the hallways of the former prison, peeking into old rooms that once housed scores of prisoners.As they traveled from the grounds to pass historical exhibits and walls of peeling paint, Kinzel discussed several topics, including the cost of prison meals and the moral implications surrounding the death penalty.

He and his students walked through a former cellblock, a tower of small cells stacked on top of one another. Crumbling paint and old furniture filled the cells, each big enough for only a bunk bed, a toilet, sink, and shelf.

For UM-Dearborn student Jacob Pennanen, the trip made him think more about the living conditions that prisoners endure. The aspiring lawyer said it was useful to have a learning experience outside the classroom.

“It kind of makes you think where you’re putting this person and for how long,” Pennanen says. “You could show pictures in class and you could show all the statistics, but it’s different actually being there and seeing what these people go through.”

Knowing Kinzel’s experiences with incarceration makes a difference, he says.

“Ten, 15 years ago, this is where he was,” Pennanen says. “Now he’s the one who can go through it and teach us to say, ‘Yeah, this is how it was, but this is how it could be better.’”

The power of teaching

While in prison, Kinzel says he learned the value of education.

Other prisoners taught him how to navigate the legal system, from filing briefs to reading case law. Combining those lessons and his own research, Kinzel worked to appeal his conviction during his stint in prison. He also fought against prison conditions, from a refusal to make accommodations for work-related disabilities to restricting access to educational materials.

In the end, he says, education got him through prison.

“[The lifers] instilled in me the positive value of education: If I don’t educate myself and become a civically engaged citizen, I’m going to be nothing,” Kinzel says.

“They taught me that if I don’t understand policy, the law, my community, and care about my community, I deserve to be here in a sense. They taught me, ‘Educate yourself, learn about the world and when you get the hell out of here, do right.’”

Kinzel is living out that lesson at UM-Dearborn, where he has taught for about four years.

He creates a safe space in his classroom that leads to students sharing their interactions with the criminal justice system or how their family members are incarcerated. He recruits and mentors other formerly incarcerated students on campus and is active in many community engagement strategies.

Taking students on tours of prisons sparks that dialogue as well.

“There’s always someone who says, ‘Well my dad was in a place like this or my mom is currently incarcerated,’” Kinzel said. “When they hear stories like mine, they feel vulnerable. They’re able to open up and talk about their own life histories as well, whether they were inside or a family member currently or formerly was incarcerated.”

UM-Dearborn senior Audrea Dakho, who hopes to attend law school and pursue prison reform, served as a teaching assistant for Kinzel and attended the Ohio trip last semester.

Dakho said that learning about the conditions Kinzel experienced in prison as well as the lack of support he received while growing up has made her passionate about finding more proactive solutions instead of imprisoning people.

“Knowing his story is like another fuel to the fire of my fight.”

(Top image: A cellblock at the former Ohio State Reformatory in Mansfield, Ohio. (Photo by Roger Hart, Michigan Photography.)

This story is reprinted courtesy of the University Record, U-M’s newspaper for faculty and staff.

Jill DeVries - 1972,1976,1982

I applaud the University of Michigan for realizing that diversity means more than ethnicity, color and cultural heritage. It is also about diverse experiences and backgrounds as well. It is those real life experiences that are the most meaningful.

Reply

Jean Miller - 2015

I Had the pleasure of meeting Aaron at the U of M, during a Auction for prisoners art programs. He is very intelligent, courteous and carries himself in a very professional manner. I found him to be very incredible, with all the hurdles he had to go through in life, to be molded for the position that he has now. I find his story very enlightening and profound, for the many who are struggling to define who they are and what gifts they have. Aaron is the type of person who was part of the problem, and came home and learned to turn that into the key to the solution. All praise go to Aaron!!!!

Reply