Put yourself in my place

A general assumption in the entertainment business is that if you can establish yourself as a successful screenwriter, chances are you’ll eventually get the opportunity to direct a film — if that’s one of your aspirations.

A general assumption in the entertainment business is that if you can establish yourself as a successful screenwriter, chances are you’ll eventually get the opportunity to direct a film — if that’s one of your aspirations.

It’s been the professional path for numerous contemporary directors, including Michigan alumni Lawrence Kasdan and Jim Mercurio. Mercurio’s new book The Craft of Scene Writing: Beat by Beat to a Better Script was the subject of last month’s “Talking About Movies” column. I reviewed it as a unique and instructive guide for would-be screenwriters that also would be of interest to movie lovers. That book led me to consider other texts written as guides for would-be film and television directors.

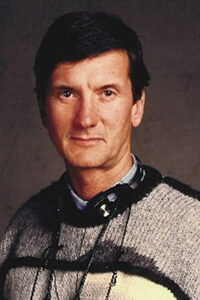

There are several, but my pick would be the comprehensive and lively work I’ll Be in My Trailer: The Creative Wars Between Directors and Actors by friends John Badham and Craig Modderno (Michael Wiese Productions, 2006). Badham directed Saturday Night Fever (1977), War Games (1983), and Stakeout (1987), among other titles. Modderno is an entertainment writer with bylines in the Los Angeles Times, the Daily Beast, and more.

The book’s subtitle suggests the tenor of the content — exploring the often complicated relationships that surface between directors and actors in the filmmaking process. Badham got the idea while teaching a directing class at the American Film Institute. He’d asked the class: “Should a director, in staging a scene, tell actors where to move and stand, or let them work it out for themselves?” A serious student raised her hand and said: “Yes, but what do you do when the actors won’t do what you tell them?”

Badham realized it would take a really long time to answer such a seemingly simple question. So he sought out long-time journalist and friend Modderno, known for his hundreds of interviews with entertainers and celebrities. The resulting collaboration would include interviews with established film and television directors offering up their candid perspectives on the vagaries of working with actors. The book would give voice to actors as well, explaining the process from their perspectives.

The writers hoped the interview-anecdotal approach would help would-be and emerging directors; they also sought to write a book that would educate and entertain fans of film and TV. With both Badham and Modderno still directing and writing professionally, the interview strategy for the book would take five years of preparation before going to press.

Can we all get along?

So, where did the text’s catchy main title, I’ll Be in My Trailer, originate? It was the late ’70s, and Badham was directing a night shoot on the upper level of New York City’s Verrazano-Narrows Bridge. John Travolta was an emerging 22-year-old actor and the lead in Badham’s film, Saturday Night Fever. It was a freezing March night with gale winds at 25 knots. In the scene, a distraught character staggers along a beam, desperate for attention. As written, Travolta’s character crawls out on the beam to help him. Badham filmed the stunt-doubles first. When Travolta learned the stuntmen had crawled, he rebelled, arguing that crawling was “wimpy” and not something his character would do. Retakes weren’t an option because the stuntmen had wrapped. Travolta walked off the set and returned to the warmth of his trailer. Trapped in a director’s nightmare, a befuddled Badham relented and told Travolta he would shoot it the actor’s way — even though the result would be a series of inconsistent edits.

Director John Badham gave in to actor John Travolta when it came to shooting a critical scene in Saturday Night Fever.

That was an early directing lesson for Badham: “If I had had competency pills that night, I would have staged the scene with the actors first, and let the stuntmen match them,” he writes. “Not the other way around. It was not John Travolta’s fault; it was my fault.” The bottom line for directors: “Never stage a scene without involving the actors at the beginning, (and) never go to the mat with your actors. You will lose. Recognize your actors’ feelings are real, not imagined.”

I’ll Be in My Trailer offers 14 chapters of wisdom by directors spanning the various aspects of filmmaking: casting, scene staging, dialogue and script interpretation, retakes, and feedback. The creative insights come entirely through the candid first-person director-actor interviews. The commentaries might read as a bit lordly in tone, but they’re never dull or lacking in educational value. I’ll Be in My Trailer presents itself as an essential “bible” for artists seeking to learn the ins and outs of directing.

I will add that the text had special meaning for me when I first encountered it. As an undergraduate and master’s student in media production classes in the late 1950s and early ’60s, I set a goal of becoming a professional director of live/live-on-tape television anthology drama series like “Playhouse 90” and “Studio One.” My dream after graduation was, “Next Stop: Greenwich Village!” More about that later.

On casting and auditions

Late director Elia Kazan once said, “80 percent of directing is good casting.”

Badham takes Kazan’s advice and recommends several key points about this critical aspect of filmmaking.

Richard Dreyfus (pictured here in Jaws) has said, “I want to feel … that I’m a creative partner in this endeavor.”

Always cast the lead actors before casting the supporting players; it is essential to understand how lead actors and those in lesser roles will connect, he says. Also, avoid actors with look-alike physical characteristics, and cast both leads and secondary actors with varying energy, tempo, and rhythmic levels. Otherwise you “put two high energy-actors like Richard Dreyfuss and Danny de Vito or two low-key actors like Candace Bergen and Jason Patric together and the result would be a mess. The high-key actors would become annoying, and the low-key ones would put us to sleep. We absolutely need the distinct differences between people to keep the scenes interesting and dynamic.”

Director Jeremy Kagan (The Chosen, “Chicago Hope”) says he makes it a point to make initial interactions with actors as comfortable as possible. “In auditions, it’s important to put the actor at ease,” he says. “When I meet someone, my initial effort is to relax him or her immediately in whatever way I can and have a conversation about something intimate.”

Once you make a casting decision, call your actors and congratulate them, the book suggests. They will feel wanted from the get-go.

The Chosen director Jeremy Kagan said, “When I meet someone, my initial effort is to relax him or her immediately in whatever way I can.”

Kazan would take an extra step in attempting to create intimacy among the cast, encouraging lunches, informal chats, and other pre-shooting get-togethers. “As a director, I do one good thing at the outset,” Kazan said. “Before I start with anyone in an important role, I talk to him and her for a long time. I make it sound like chatter.”

Actors seem to respond favorably to this kind of treatment.

- Richard Dreyfuss: “You want to feel welcome. You’re here because they like your work.”

- Anne Bancroft: “Relaxation is the key to acting. Most actors will relax if you tell them they’re the best thing on God’s Earth.”

- Frank Langella: “No matter where the actor is in his work, no matter how young or old — he needs the director to communicate confidence in him.”

Directors interviewed for the book repeatedly pointed out the importance of psychology classes and immersive acting workshops so directors could better relate to the actors on set.

- Director Mark Rydell: “It should be mandatory that every director act and experience acting.”

- Director Richard Donner: “I think it’s the best thing anyone can do. Spend a lot of time in acting class. At least get the basics. Because then you have the same fears the actor has.”

As a college student, I aspired to be a director. I got small parts in Tennessee Williams’ “Summer and Smoke” (a waiter with a couple of lines) and “The Matchmaker” (a butler with three lines). I auditioned because I wanted to observe actors at work. Sometimes I would sign on as the stage manager of major productions — e.g., Dylan Thomas’ drama “Under Milk Wood.” Though I had no intention of becoming an actor, I was able to apply what I had absorbed when as a graduate student I directed my first full-length, live-TV drama: Tennessee Williams’ “The Glass Menagerie.” The cast, mostly my age, knew of my background and trusted me, I think.

Rehearsals

“I always like improvisation, and the beauty of it is, you don’t have to use it,” said director Roger Corman.

Directors and actors tend to hold different views regarding the value of pre-production rehearsals.

- Director Jeremy Kagan: “I think rehearsal is a magical time, (in read-throughs) hearing the script as a whole … you can really work a scene and discover what the scene is about … you can do improvisational work.”

- Actor Laurence Fishburne: “I love rehearsal on the stage, but film, no. On film I like to swing; just put me on the street and let me go.”

- Actor/director Jodie Foster: “I only rehearse emotional scenes for blocking and for what we are trying to do. I never, ever, blow an emotion on a rehearsal.”

- Director Martha Coolidge, former president of the Screen Actors Guild: “In a comedy, I don’t particularly like a full-out rehearsal on set before shooting. I like to walk through it, block it. I don’t like to blow it and lose the spontaneity of the moment.”

- Director Roger Corman: “I always like improvisation, and the beauty of it is, you don’t have to use it. If they improvise a scene and it’s no good … you don’t even have to print it.”

The text concludes that actors may like and need different kinds of rehearsals. But the central point of any rehearsal method is that the actor feels comfortable in the character’s shoes when it comes time to shoot.

Staging, shooting, and retakes

Another value of read-throughs in preparation for staging and filming is that actors get to listen to one another. Gary Cooper has been quoted as saying, “I’m not a very good actor. I’m just a good listener.” Similarly, John Frankenheimer, a noted film and “Playhouse 90” director, said of Robert De Niro: “You never have to say anything twice to De Niro. That quality comes across on the screen too. He listens. I think so much of acting is reacting. It’s listening.

“Pinch-Ouch!!” is the basis of acting, i.e., “Act-React.”

The authors suggest that when working to access the heart of a scene, the director should break it down into objectives described with active verbs. A standard verbally active question might be: “What are you trying to get from him?” “What do you want her to do?”

They suggest avoiding philosophical, abstract interpretations that move the actor away from the story elements within a scene. Stay in the story! Actors should focus on what the characters are trying to do. Over-intellectualizing a scene won’t help. Remember: the beginning of every film scene begins with “Action!”

A couple of other do’s and don’ts from the text: Do tell the actors to strike emotional cues from a screenplay that may lead to cliched responses. e.g. “angrily, “bitterly.” Don’t give actors line readings. And don’t allow the screenwriter or anyone else on the set to offer “helpful suggestions.” That’s the director’s job.

Retakes

Some directors (Warren Beatty, for example) shoot abundant retakes; others (Clint Eastwood) shoot little or none. The authors recount an anecdote when actor Eastwood was working with a rookie director who favored multiple retakes. After one lengthy set, the director called “Cut!” and said, “Clint, that was perfect. Next time . . .”

He never got to finish the sentence. Eastwood said curtly, “Kid, perfect is as good as I get,” and headed to his trailer. The authors advise: “Always give specific, logical reasons for a retake — one that makes ever-sensitive actors feel okay.”

Sensitive scenes

Always discuss sensitive scenes — and those featuring sex and nudity — before casting an actor. As Badham notes, “There are strict Screen Actors Guild rules which protect actors from having to do any nudity that hasn’t been previously discussed with them and agreed to in writing.”

- Director David Ward: “Most actors don’t like to do sex scenes. Most directors don’t either because it’s hard to do them in a way that’s really sexy and it’s hard to do them in a way that’s original.”

- Director Martha Coolidge: “[I tell my actors] ‘This is choreography. Love scenes are not real. If you don’t want to do something or you don’t want something seen, we’re going to stage it so the camera can’t see it.”

- Cinematographer Jon de Pont: “In Basic Instinct, that one famous shot set the whole relationship. Sharon Stone didn’t want to do it originally. I had to shoot the shot myself. I said, ‘Sharon, you have to spread your legs a little more; otherwise it’s not going to work. I have to see something.’ She said, ‘I don’t want to see it.’ I said, ‘Don’t worry about it too much. In this scene, we’ve got to get a sense that you’re not wearing anything, otherwise the whole scene, we might as well throw it away.’

Feedback

“An actor has to have compliments,” according to actor Ruth Gordon. “If I go long enough without getting a compliment, I compliment myself, and that’s just as good because at least then I know it’s sincere.”

“When filming, the actor is dependent on the director for feedback,” Badham says. “Feedback is essential to the actor’s performance. Just what constitutes good feedback is at the heart of this book.”

But the director is just as dependent on the actor, he stresses. “If we don’t listen to actors we might as well use computer-generated characters that do what we tell them to do. They will be about that interesting, too.”

And to get the best out of your actors, always have personal actor conversations in private, not in front of the crew and/or cast, he says.

Talk to every actor after every take if only to give a reassuring nod. Don’t be afraid to say when a performance isn’t right, but find positive ways to phrase your comments.

- Actor Richard Dreyfuss: “I want to be able to feel with a director that I’m a creative partner in this endeavor.”

- Director Oliver Stone: “Too many directors say, ‘That’s great, that’s great,’ to where it doesn’t mean anything. Or ‘It’s good, but…’ which is a horrible way to start a conversation. I wait and then go to them and say, ‘This is what I thought you were trying to do.’”

- Director David Ward: “What you don’t want to do is discourage your actors. You don’t want to break their spirit by being too controlling, too critical. You have to be critical in a positive way. If you’re not, they will sense it right away.”

- Actor Ruth Gordon: “An actor has to have compliments. If I go long enough without getting a compliment, I compliment myself, and that’s just as good because at least then I know it’s sincere.”

- Director Jeremy Kagan: “I often say to certain actors, when I’m meeting them, ‘Tell me what works with you. We haven’t worked together. Tell me what helps.’”

Final thoughts

This overview only touches on the vast range of authoritative wisdom in I’ll Be in My Trailer. Through the brief chapter highlights, I hope I’ve been able to suggest what this guide promises for the director and actor. Its significance has been pointed out by the great film/television director John Frankenheimer. When interviewed by the authors just before his untimely death, Frankenheimer said, “Directors have needed a book like this since D.W. Griffith invented the close-up. We directors have to pass along to other directors our hard-earned lessons about actors. Maybe then they won’t have to start from total ignorance as I did. Like you did. Like we all did.”

Personal Post-Note: My goal of “Next stop: Greenwich Village” ended in 1962 with the completion of graduate school. I had used deferments to finish my degree and I was at the top of the list for the military draft. I said, ‘Let’s get it over with,’ and soon I was off to Ft. Jackson, S.C., for basic training, then Army Security Agency intelligence schooling at Ft. Devens, Mass., followed by a year of surveillance duty in Saigon, monitoring the Morse code transmissions and movement of elusive Viet Cong units who roamed the South.

On entering back into civilian life in January 1965 with my wife, Gail, and two small children, I pursued a career as a college teacher. A PhD in 1970 in Speech Communication and Theater at the University of Michigan underwrote that ambition, and I was able to stay in Ann Arbor for three-and-a-half decades teaching classes in film and television production.

I had some of the best media students on the face of the planet. I never looked back, but, oh, how I wish that I’ll Be in My Trailer had been there for my students and me. Every time I pick up the book, I find myself absorbed in every page because it’s a timeless, one-of-a-kind guide for media directors and actors. Oh yes, and teachers.