Nighttime is the right time

Night often finds Anne Danielson-Francois following a wooded deer trail to the banks of the Rouge River in Canton, Mich. This associate professor of biology at the University of Michigan-Dearborn leads her students into the shallow water to point cameras at the nearby trees. That’s where they make movies of spiders having sex.

For the past 15 years, this arachnologist has focused much of her research on the little-known and unusual mating behavior of a common spider, the long-jawed orb weaver (Tetragnatha elongata). It loves to hang out in foot-wide webs spun in tree branches over water.

The professor and her students, all draped in mosquito netting, will stand in the river with their tripod-mounted high-resolution 4K video cameras for as long as four hours. They hover inches away from the webs to catch the action. Then, back in the lab, the students spend months poring over the footage.

Danielson-Francois hopes her research will advance the understanding of how sexual selection shapes male and female traits, including sperm competition.

Gone a-courtin’

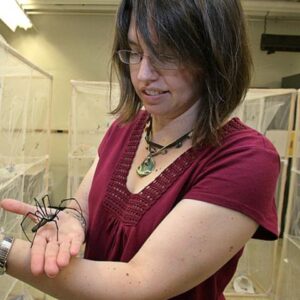

This male is “just wandering between female webs,” the biologist says. “He’s looking for a chance to either mate or steal prey from a female.” (Image courtesy of Danielson-Francois.)

Many spider species have courtship rituals. Not these two-inch long twig-mimickers. “We know they’re interested in mating when the female is sitting there hanging with her jaws, her chelicerae, open. The male approaches and they just run at each other and grasp each other by their jaws. Occasionally, she eats him, usually after they’ve mated. Sometimes she eats him before,” says Danielson-Francois.

It is extremely rare for the female to find herself on the menu, and only when prey is scarce. Instead, many times the male gets lucky twice. Afterward, he sometimes steals prey from his mate’s web and scurries off.

Danielson-Francois demonstrated in a research study that, unlike other spiders, females of this species outnumber males and welcome many suitors, generating intense sperm competition inside the female’s reproductive tract.

“We’ve discovered that a male can scoop out previous male sperm and put his in,” she says. “What’s happening is sperm competition inside the female, and that’s why a female isn’t picky — she just lets the sperm duke it out inside her.”

Unlike many other species, these females can pop out as many as 10 batches of egg sacs; each contains 100 eggs.

She likes to watch

Danielson-Francois’ lab in the Department of Natural Sciences building on the UM-Dearborn campus often hosts as many as 300 spiders under observation. Danielson-Francois, who has served as Biology chair, has trekked from the jungles of Asia to the Louisiana bayous to observe spiders and collect specimens.

From Taiwan, she brings back giant Golden orb web spiders (Nephila pilipes) with help from her collaborator Dr. I-Min Tso of Tunghai University. To house them, she builds five-foot tall cages with walls made of bridal veil fabric, a material spiders’ feet and claws can grab well.

While shopping in bridal stores for bolts of the sheer stuff, Danielson-Francois sometimes has to correct well-intentioned clerks. When they congratulate her on her impending marriage, she tells them the real purpose of her mission. “I get a lot of weird looks,” she says.Females of the Taiwan species have curved, elegant black legs which can span more than a foot. By contrast, the males are tiny. They “capture” the female by spinning silk around her abdomen. Females spin their webs of golden silk; their webs can be six-feet across.

“They’re extremely tough,” says Danielson-Francois. “I’ve literally kind of bounced off Nephila webs because they’re so strong.”

To save energy, spiders typically eat their webs and recycle the silk’s proteins. Before rain falls, they take down their sticky traps by consuming them. “They use their legs to just shove the silk into their mouths, and they can do it really quickly,” she says.

Expert analysis

This female is well-camouflaged on a dried leaf, waiting for prey near her web so she can run out and catch it. (Image courtesy of Danielson-Francois).

There are only 200 arachnologists in the U.S., 40 percent of whom are women, according to the American Arachnological Society. In recent years, Danielson-Francois has become a go-to expert for reporters from USA Today, Parade magazine, CNN, and other media outlets. She has been quoted in stories on tropical spider smuggling and spiderlings (baby spiders) parachuting on “balloons” of silk.

She made The New York Times after the Shapiro Undergraduate Library on the Ann Arbor campus asked her to identify spiders in its basement. The administration feared they were deadly brown recluses. Indeed they were. Though the library locked up for two days to stamp them out, it later apologized and called the closure “a misunderstanding of the situation.”

If Danielson-Francois had her way, such hysteria would be a thing of the past. She hopes more people come to see these eight-legged creatures as she does — as gorgeous objects of wonder. “I think the only way you can get a love of spiders is to encounter them, see their beautiful webs, and watch them eating mosquitoes,” she says.

“People have a misperception that spiders are aggressive,” she adds. “They’re beautiful. They’re very gentle.” She calls her Tetragnatha “absolute wimps. They get too hot, they die. They don’t get enough water, they die. If you scare them, they instantly freeze, or they run and then freeze.”

Reap the benefits

The ways in which spiders benefit humans far outweigh their dangers, the researcher says. Only two U.S. species are venomous — the black widow and brown recluse — and their bites, though medically concerning, are extremely rare. Spiders devour household pests like ants, and in malarial areas, studies have shown that people who live in homes with spiders are less likely to contract the disease.

Her young daughter Lexi loves to play peek-a-boo with agelenid funnel spiders in her lab. When she blows on one of their webs, it darts down its hole. When it pops back up, she puffs again. “They’re fun when you realize they’re not charging out to bite you,” says Danielson-Francois.Like her daughter, the scientist’s fascination with creepy crawlies began as a child. She led neighborhood kids on tours of her backyard to show them worms and bugs. When she was 10, she had a pet tarantula named Dracula. As a teenage camp counselor, part of her job was ridding tents of spiders. And though she squashed some with flip-flops, the tender-hearted teen shooed them out more often than not.

If someone finds a spider at home, Danielson-Francois recommends live-and-let-live. But if the spider can’t be tolerated, the best remedy is to put a cup atop it, slide a sheet of paper underneath, and put it outside.

“It’s probably just a lost male looking for love in all the wrong places,” she says.

Patrick CARDIFF - 1990

I had a full-grown cinnamon tarantula, Shelob, as a pet in my undergrad years.

We frat brothers used to all gather round once a month and watch her hunt down and feast on a pinkie.

She made a wonderful companion. Very special – with four sets of book lungs rather than two – I loved that bug!

Arachnologists like Anne Danielson-Francois are parsing the most diverse set of species in the animal kingdom.

Hats off to all you do, Anne!

Reply

Dennis Francisco - 1971

Well-written article on a very interesting topic and UM-Dearborn instructor/researcher.

Reply

Dorothy McLeer - '97 and '08

I have had the pleasure of learning from and teaching with “Dr. A.”

UM-Dearborn is so fortunate to have such an accessible and knowledgeable educator who cares about her students and her subject matter. She really “gets it!”

Reply