Hollywood history is safe and sound in Special Collections

(Image courtesy of U-M’s Special Collections Library.)

“Well, Hollywood turns out to be just exactly like Hollywood.”

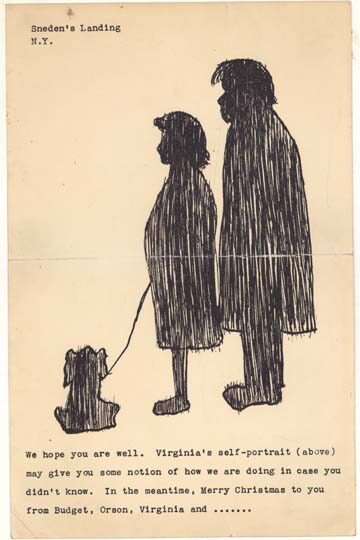

So begins a missive sent July 22, 1939, from filmmaker Orson Welles to his first wife, Virginia Nicolson. The New York auteur had just taken up residence on the West Coast to launch his movie career at RKO Studios. Nicolson, for her part, was on a European holiday. Not even a year had passed since Welles gained worldwide notoriety for his all-too-realistic radio production of H.G. Wells’ science fiction masterpiece The War of the Worlds. From the sound of his letter, he was rethinking his choice to leave the Big Apple: “Hollywood, as I predicted, is not a nice place to go out in.”

This original typewritten correspondence is part of a recent acquisition by the Special Collections Library at the University of Michigan. The University is now home to four unique Welles’ collections, comprising the the most extensive international archive on the filmmaker, actor, director, and writer, who is perhaps best known for the movie Citizen Kane.

Such unedited musings from the collection of Welles’ eldest daughter, Chris Welles Feder, provide a rare and intimate perspective on Welles’ inner life. He writes of renting a backyard bungalow at the infamous Chateau Marmont on Sunset Boulevard, driving a Cadillac convertible down Wilshire Boulevard, and meeting with film studio executives.

“A new fellow has come into our world by name of Frantz, who is a boy wonder at tax evasion,” he reports in the 1939 letter to his wife. “We met him very casually at the tavern in Chicago, and took him with us to Hollywood to work on the contracts, with a view to withholding a little more than 35% from Uncle Sam. He turns out to be very good at this and I have every reason to hope that we can buy a farm with what he saves. Hurrah!”

The Big Picture

The collection includes rarely seen photographs of Welles as a boy. (Image courtesy of U-M’s SpecialCollections Library,)

Welles, who died at age 70 in 1985, is renowned for his innovative work in radio, theater, television, and film. The newly acquired material at U-M includes substantial information about different periods of Welles’ career, from his youth to the end of his life. The previously held materials include detailed work for his unfinished projects, including It’s All True, a documentary-fictional film about Mexico and Brazil, which he worked on in the early 1940s.

Meticulously catalogued and kept in protective boxes, the entire collection totals nearly 100 linear feet, including thousands of documents, letters, telegrams, scripts, production and financial statements, photographs, illustrations, and audiovisual materials.

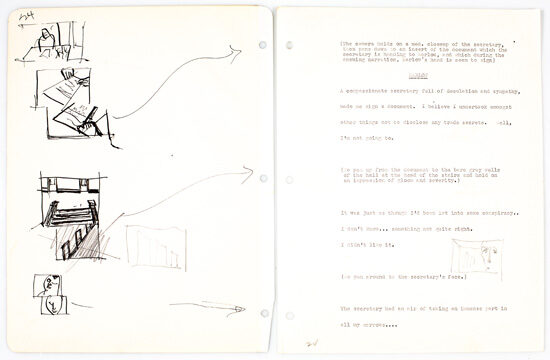

“The different versions of scripts with his handwritten notes and sketches in the margins show different stages of his creative process,” says Peggy Daub, curator and outreach librarian at the Special Collections Library.

Among the new items of personal interest donated by Welles Feder are private photographs of Welles as a child and additional letters to Nicolson, which coincided with the beginning of his film career, as well as materials related to the 1949 movie Macbeth, in which Welles Feder played a role.

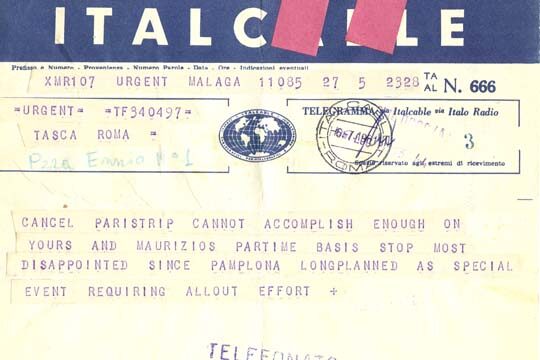

Other vital additions to the Welles archive come from the estate of Alessandro Tasca di Cutò, purchased at an auction in London. Tasca was a producer and longtime friend of Welles. Artifacts include materials related to two films especially important for Welles, Chimes at Midnight (1965, also known as Falstaff), filmed in Spain, and Don Quixote (1955-73, unfinished), filmed in Mexico, Italy, and Spain. In many letters, notes, and memos, the Tasca collection illuminates Welles’ day-to-day work and sometime frustrations as a filmmaker.

Welles with collaborator Alessandro Tasca di Cutò (center). (Image courtesy of U-M’s Special Collections Library.)

In one especially colorful memo, he derides Tasca for neglecting to keep him informed of financial matters on a problematic production. The letter is a followup to a terse telegram Welles sent to his partner, who’d attended his own daughter’s wedding, but had neglected to inform Welles of his plans. The ill-timed event conflicted with a shoot Welles had scheduled for them in Pamplona. Clearly the director was not used to playing second fiddle, even to a young bride. The emotion is virtually palpable in the erratic font from the manual typewriter.

“You will say, with justice, that a man’s daughter doesnt [sic] get married very day in the week,” Welles practically spits onto the page, amid scribbled edits and insertions. “But to this I must answer that I dont [sic] see why this particular daughter had to pick that particular day in that particular week . . . You certainly knew– I had certainly told you often enough– how important Pamplona was to us, crucially important.” The next sentence, still visible through a thick line of blue ink, is most revealing of Welles’ uncontrolled angst: “Yet the wedding was held precisely on the day [illegible] to keep you away from Pamplona.”

Roll Credits

These newer collections at U-M supplement two other Welles collections, the “Orson Welles–Oja Kodar Collection” and the “Richard Wilson–Orson Welles Collection,” both acquired in 2004-05 and available to researchers for several years.

Of particular interest to researchers is the archival documentation on Welles’ cinematographic mission to Brazil and Mexico, where his initial intention was to portray true stories of Latin American cultural life and society during World War II as part of a U.S. Good Neighbor propaganda film.

Welles went beyond reproducing the clichés of popular culture and simple perceptions of the Rio Carnival. Instead, he showed an incisive and revealing look at Brazilian society, including the historic journey of raftsmen, or jangadeiros, to Rio from the Northeast. The film was ultimately rejected by RKO studio management and the Brazilian government’s Department of Press and Propaganda.

Also included in the archive are photographs, screenplays, and other documents from Welles’ major films produced in Hollywood, Mexico, North Africa, and Europe from the late 1940s to the early 1970s, screenplays for works-in-progress, and materials pertaining to his theatrical productions in the U.S. and Europe.

Former U-M professor Catherine Benamou, author of It’s All True: Orson Welles’ Pan-American Odyssey who now teaches at the University of California-Irvine, propelled the acquisition of the first two Welles’ collections through connections with his family and close collaborators.

The Special Collections Library at the University of Michigan holds internationally renowned collections of books, serials, ancient and modern manuscripts, posters, playbills, photographs, and original artwork. It is home to some of the most historically significant treasures at U-M and is open to the public. Collections do not circulate; material is retrieved upon request for use in a reading room. See a listing of holdings in the Special Collections Library.

Anonymous

Hi! Someone in my Facebook group shared this website with us so I came to check it out. I’m definitely loving the information. I’m book-marking and will be tweeting this to my followers! Great blog and superb style and design.

Reply