The tide turns

The largest of all the antiwar protests of the 1960s in Ann Arbor happened on Oct. 15, 1969. It was part of the Moratorium to End the War in Vietnam, a nationwide event that brought out more than a million Americans, from radical leftists to worried suburbanites accustomed to voting the Republican ticket.

On the campus, with most classes canceled for the day, students spilled into teach-ins and forums. Plans for a massive evening rally outgrew Hill Auditorium, then Crisler Arena (then called the University Activities Center), culminating in a torchlight parade that wound from the Diag to Michigan Stadium, where the crowd swelled to 20,000 or more.

In the days before the Moratorium, President Richard Nixon had stated flatly that “under no circumstances whatever will I be affected by it,” and when it was over, Vice President Spiro Agnew dismissed it as the handiwork of “an effete corps of impudent snobs…hardcore dissidents and professional anarchists.”

But the Moratorium was so massive that Vietnam hawks could no longer make a credible case that opposition to the war was confined to long-haired hippies hoping to avoid the draft. Such a massive demonstration was seen as further proof, if any were needed, that the American mainstream had turned against the war.

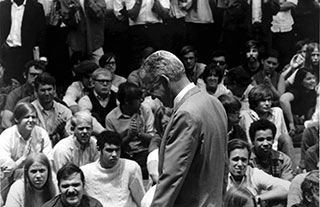

An instinct for compromise

U-M President Robben Fleming speaks to students shortly before he came out against the war in Vietnam, September 1969. (Image: U-M’s Bentley Historical Library.)

The Moratorium was overwhelmingly peaceful — a fact that enhanced its credibility among pundits and the public. That was a victory for the temperate wing of the antiwar movement. For that, a small share of the credit may belong to U-M President Robben Fleming.

Fleming had arrived in Ann Arbor in 1968 after several years as chancellor of the University of Wisconsin. A skilled labor negotiator, he brought an instinct for compromise to his new job. This proved helpful as he navigated a tricky passage between student radicals to his left and stern defenders of University prerogatives to his right, from Republican regents to conservative alumni.

Early in his presidency, he made concessions to student protesters on several fronts, a strategy that drew admiration from the left and brickbats from the right. But at the start of the fall semester in 1969, he was taking a tougher line against student activists trying to shut down U-M’s Reserve Officer Training Corps (ROTC) program. He was increasingly concerned lest the tide of protest engulf the free exchange of ideas, and he hinted that he would not look kindly on any cancellation of classes on the day of the Moratorium.

In private, Fleming had come to see the war in Vietnam as a tragic blunder, a misguided extension of American power that was bringing deep harm to the nation. But he had no sympathy for radicals who painted the war as a symptom of deeper corruption at the nation’s core, and he was determined to oppose any disruption of the University’s basic business of education.

That view would soon be put to the test, he realized, with plans for an antiwar planning conference, called a “Tactic-In,” on Sept. 19-20, then for U-M’s participation in the national Moratorium set for Oct. 15.

Pros and cons

Antiwar rallies were common in the late ’60s, but the October 1969 Moratorium to End the War in Vietnam stood out from the rest. (Image: U-M’s Bentley Historical Library.)

Early in September, in the midst of anti-ROTC protests, an antiwar U-M faculty group asked Fleming if he might be willing to go public with his opposition to the war at the approaching “Tactic-In.”

Fleming weighed his options. In a confidential memo to his vice presidents, he asked for their thoughts and expressed his own:

“There are pros and cons to doing it. If I speak, I have already told them I will talk as a moderate who is opposed to the war and thinks we ought to get out of it, but who will also say unkind things about the fascist left. This will probably draw booing from the audience that can be expected.

“There will be criticism, some of it vigorous, if I speak. On the other hand, the subject is urgent, the gamble that we can take the leadership and place it in the hands of the moderates rather than the extremists is attractive, and I personally feel deeply on the subject.”

Fleming was putting his finger on a key question — whose views would dominate the campaign to end the war? The radicals who had first raised the antiwar cry? Or the liberal and moderate late-comers now joining the fight?

“The issue,” as New York Timescolumnist Anthony Lewis put it, “is whether to try to enlist the mass American public against the war, by moderate techniques, or to go for more militant protest.”

Strange bedfellows

Fleming decided to speak at the Sept. 19 “Tactic-In.” The venue would be Hill Auditorium. He would appear on the stage just before Rennie Davis, a media-star leftist and a member of the “Chicago 7,” then on trial for inciting riots at the 1968 Democratic National Convention in Chicago.

At the appointed time, Fleming stepped into Hill’s waiting area behind the stage. He was alone. The auditorium was packed, but his jitters were due not just to the speech. He was also thinking of his encounter with Rennie Davis — with whom, it happened, Fleming was already acquainted, though Fleming didn’t know if Davis would remember.

More than 20 years earlier, after his Army service in World War II, Fleming had worked in Washington with Davis’ father, John C. Davis, a labor economist who was chief of President Harry Truman’s Council of Economic Advisers. As a little boy, Rennie Davis had played in the Flemings’ Washington apartment.Now he was a fire-breathing radical at the head of a national movement. What would he say to his father’s old friend?

The door to the waiting room opened and in walked Davis. Instantly the younger man reached out his hand, smiled broadly and said: “Gee, it’s good to see you again! My folks send their warmest greetings!”

“Rennie,” Fleming said, “one of the last times I saw you, you threw up on our floor.”

With that, Fleming walked out on stage and delivered his prepared speech — a deliberate and reasoned summation of the emerging mainstream consensus against the war.

“A matter of personal conscience”

Fleming was a skilled negotiator with an instinct for compromise. (Image: U-M’s Bentley Historical Library.)

“I accepted the invitation to be here tonight as a matter of personal conscience,” he told the crowd. “I share the agony of all those who oppose the war in Vietnam. I happen not to agree with the views held by the radical left. Nevertheless, I am not here to criticize others who oppose our Vietnam policy, but to state my own views.”

Immediately after World War II, he said, the Soviet Union had seemed a monolithic force in danger of conquering the world. But time had “taught us the error of this greatly oversimplified analysis of the communist world,” which was as fractured and contentious as the western alliance.

“From this view,” Fleming said, “I draw the conclusion that it is not a disaster for us if Vietnam ultimately becomes an independent communist country.

“To suppose that one can impose the American concept of democracy on countries which have no democratic traditions, no heritage like ours, no organized political parties, too few educated leaders, and strong military traditions defies rationality.”

So, he said, he had concluded “our present involvement in Vietnam is a colossal mistake.”

That did not mean he shared the radical left’s view that “it is all the result of evil and corrupt forces which govern our society. My own life experience is that honest mistakes can be made.” But now, “the economic, human, spiritual costs of continuing the war seem to me unbearable.”

He ended with a promise — that he would make University facilities available for the Moratorium, and if, on Oct. 15, enough students and faculty turned out to fill Crisler Arena to express their opposition to the war, then, “I shall be glad to carry their message to Washington.”

As reaction flowed in — most of it welcoming Fleming’s remarks, some accusing him of being a patsy for Communism — he moved to accommodate plans for the Moratorium.

Speakers of all stripes

The Diag always has been a gathering place for student activists. (Image: U-M’s Bentley Historical Library.)

On the question of canceling classes Fleming oversaw a compromise. The University as an institution would not take an antiwar stance by closing down. But individual faculty members, acting on their own, would not be penalized for canceling classes (so long as they were made up later), nor would students who missed class to take part in Moratorium events.

Fleming’s main concern was to avoid the violence that might be sparked if the University dug in its heels against the Moratorium organizers.

“There will unquestionably be speakers of all stripes on the campus that day,” he wrote an outstate colleague. “They will represent everything from left to moderate. I believe the hope is that the day will be completely non-violent and in that way have its maximum effect. If luck is with us, that hope will be realized. We will be wiser on October 16.”

Carrying the message to Washington

The Moratorium in Ann Arbor, as elsewhere, went off without so much as a broken window, and Fleming kept his promise by writing a letter to President Nixon to convey “the mood of our campus with respect to the Vietnam war,” which he reported as a mood of “broad and deep opposition. This opposition is not simply emotional, it is thoughtful. It does not occur because of ignorance, but only after sober reflection.”When an Ohio industrialist wrote Fleming to suggest his actions had given “aid and comfort to the enemy,” Fleming replied in his cordial style: “There is very strong anti-war sentiment on our campuses. One can deal with it in two ways. One is to try and suppress it, which will almost certainly lead to violence. The other is what we have tried to do. October 15 went off without violence, and with some 20,000 people in the stadium for a final presentation.”

An alumnus expressed a more common reaction to Fleming’s approach: “I am proud of my university and its choice of a president. What a world this would be if all administrators were like you. What a world this would be if we who were so full of idealism as students did not have to grow more narrow-minded, reactionary, and bigoted as we grow older.”

Sources included coverage in the Michigan Daily and the Robben W. Fleming papers at U-M’s Bentley Historical Library.

(Top image: Tom Hayden, ’61, on leave from his trial as one of the Chicago Seven, prepares to address antiwar demonstrators at U-M’s observance of the Moratorium to End the War in Vietnam. Photo by Jay Cassidy, courtesy of U-M’s Bentley Historical Library.)

Mark Smaller - 1973; B.A., English

As a freshman, I had 2 encounters with President Fleming. As President he hosted a tea for new students at his home on South University. I met him and found him welcoming, warm and friendly. The second time was during a demonstration where a friend and I were accidentally locked inside the administration building. We went upstairs and discussed the demonstration with President Fleming, and our support. He was interested in our views, and listened. He was a model to me regarding leadership and especially during difficult times as those days were.

Mark D. Smaller, Ph.D.; President, American Psychoanalytic Association

Reply

Mike Jefferson - 1988

Yawn, that’s all Ann Arbor is about; leftist rhetoric, micro aggressions, banning words, BLM, social justice, global warming, and other lies. It’s really tired already. When did excellence, achievement, and innovation escape from the university’s mission?

Reply

Joanna Connelly - 2013

There is no mention here of micro aggressions, banning words, BLM, or global warming. This article is about events that occurred in 1969; your comment seems misplaced.

Reply

Mary Baron - 1969 (MA: English)

In response to the Vice President’s comment on dissent:

Vice President Spiro Agnew dismissed it as the handiwork of “an effete corps of impudent snobs…hardcore dissidents and professional anarchists.”

The entire faculty and audience at commencement rose and sang the National Anthem. As a graduate student, I taught classes in the stair wells.

Mary Baron, PhD

Reply

Jim Hallett - 1972

Robben Fleming was indeed a wise leader who was able to balance the many factors involved. While the Vietnam War was a mistake, UM or any university, is not called upon to render political opinion in lieu of conducting classes. The fascist Left (article reference) is still very alive at Michigan and the propaganda is ongoing. Since I was a student at the time, I appreciated the fact we had no violence on campus, but I continue to see some of the same demagoguery (as those of the anti-war movement) come out in attempting to quash any sentiment that varies from the “progressive” establishment.

Reply

Larry Carter - 1969 BS(ME)

I graduated in May 1969, BS(ME), was commissioned in the Air force on the same day, and by October 1969 I was already half way through pilot training with several other of our May graduates. Many of those not responding to the call of the draft, or patriotism, still celebrate these and other protests as noble and a few even felt justified at the time to disrespect fellow students in uniform on campus. I am also from that era but see things somewhat differently. I was saddened when friends were shot down, lost their lives, or taken prisoner. I also believe the folks who set the bomb off in North Hall that same year were not noble protesters but terrorist no different than the ones recently active in Paris or Brussels. I am pleased that most in our county are now able to separate the feelings they have for our service members and the judgements they hold for the conflicts in which our elected leaders have chosen to engage.

Reply

Michael Cary - 1972 - AB Psych

I was a sophomore that day; I think I walked around in some kind of march on the Diag and listened to some speeches. The next day in class I asked if the POTUS really cared about a bunch of college students marching around campuses instead of going to class. I felt good about participating, not sure how much of a difference it made. S T Agnew’s comments about me being an “effete snob” have stuck with me today. ’68 to ’72 were turbulent times – wish I could do them all over again!

Reply

Gary Allard - 1973

I was a new freshman in fall of 1969 and enrolled in Navy ROTC program too! I don’t recall these specific events although I certainly remember the charged atmosphere in general. I do remember being very nervous about wearing my uniform on campus every Wednesday, especially walking across the Diag, but actually I can recall being hassled only once and that was in the dorm by a fellow resident. Most people had a “live and let live” attitude despite what they thought about the war. The primary target of anti-war protesters was not the ROTC staffs or students, but North Hall itself, as the symbol or “face” of the military. It was trashed on a regular basis over the next few years until the peace agreement was settled in 1973 just before graduation. President Fleming certainly showed his leadership in keeping the campus from ripping apart in those years.

Reply

Steve Rauworth - 1970

I wonder what Fleming thought in his latter years, when it became apparent to more than the radical left that during the Vietnam War, and increasingly ever since, that “it is all the result of evil and corrupt forces which govern our society.” This whitewashed piece of historical revisionism, however accurate it may in its very limited context, doesn’t reflect the impression of Fleming I (not at all a flaming radical then) and most students I knew had of him during those years, which was as an apologist for the status quo.

Violence is of course to be avoided if possible, and Fleming’s role in the events of October 1969 in Ann Arbor helped avoid it. However, It is a strange conceit of liberals, then and now, to passively-aggressively embrace their precious nonviolence in a facade of wanting change while being complicit by paying taxes to and enjoying the riches and protection of a government whose foreign policy and military forces use over half the national budget for intimidation and violent aggression in maintaining USA superiority throughout the world.

Reply

Harrison Smith - 2012

I sincerely appreciate the well written history that’s consistently conveyed through Michigan Today. It gives me a chance to learn about the rich history of the University, and think about how different things were in all the places I knew.

However, can the editors of this publication please make sure that high resolution photos are reliably added to all pieces? And make sure that these higher resolution photos are opened by default when clicking on the images? I’m sure these aren’t the highest resolution versions of these photos available, and it’s a shame not to be able to resolve anything in this fantastic photographs.

Reply

Joe Zengerle Zengerle - Law 72

Lynda and I entered the law school together in August 1969. I had worked as a special assistant to General Westmoreland in Vietnam in 1968, during the Tet Offensive. I later had Robben Fleming for an elective in public unions. Neither of us recall the moratorium. I wonder of the law school did not cancel any classes for it? We remember quite well the effort of the Black Action Movement to shut the law school down because the Regents would not agree to a 10% quota for admission of black applicants.

Reply

Chris Campbell - MA, 1972; JD, 1975

Our experience since the war ended has certainly confirmed Pres. Fleming’s appraisal of it as a “colossal mistake” and his comments about trying to impose democracy on countries with other traditions. Then there is the always-interesting issue of American economic interests, which certainly factor in our current endless war. The difference between then and now is that in 1969 the draft drew in cannon fodder from the entire society, whereas now the burden of war is borne only by those who do not question leadership and view service as a patriotic duty. We seem to reward their patriotism mostly by ignoring them when they return with various kinds of scars. I wish there were more passion about the current war.

As a student beginning in 1971 I tended to see University leadership as timid in not wholeheartedly opposing the war by any means possible. As an older guy, I now see the value in a sort of institutional neutrality that lets a university do what it does best–debate ideas.

Reply

Dennis Werling - Rackham, 1968

In November 1969, over thirty buses from U of M carried students to the “March Against Death” in Washington, DC. That, too, was largely peaceful except for a Weatherman demonstration at the Justice Department. And the war went on.

Reply

Carolyn Chartier Bloom - 1970

I was a senior in LSA that year. I had cut classes to campaign for Gene McCarthy the year before, and contrary to my parents, had come to oppose the war in Vietnam and the domino theory espoused by politicians. The moratorium day was peaceful, instructive, and energizing. It culminated with a speech by Tom Hayden, Michigan alum and co founder of Students for a Democratic Society. At that rally, I met fellow student Leslie Bloom, a Vietnam vet who had been a combat medic. We marched on Washington the next month and married the next year. The learnings from these events have formed my beliefs for the next (nearly) 50 years. I’m an old woman now, a social worker still practicing and working for peace. Thank you, Michigan.

Reply