America’s family tree

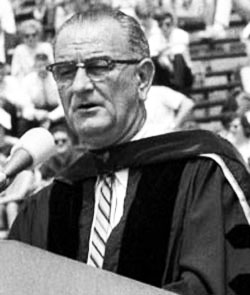

The year was 1964. The U.S. was about two decades out of the Great Depression, the national poverty rate hovered around 19 percent, and President Lyndon Johnson was seeking ideas for a radical domestic program to inspire American voters — many of whom were still grieving the death of John F. Kennedy.

At U-M’s Spring Commencement that year, President Johnson outlined a loose plan to declare “war” on poverty and create a “Great Society.” He was elected in a landslide that fall and set about making good on his promise.

Congress responded by forming the Office of Economic Opportunity, developing policies designed to help the nation’s poor. In 1966 and 1967, in an effort to track whether its programs actually worked, the government targeted some 30,000 American households and embarked on interviews.

Understanding the value of continuing to track people in poverty, the government researchers approached Jim Morgan, an economist with the U-M Institute for Social Research (ISR). They wanted him to continue a survey of 2,000 low-income families over a period of five years.

Morgan was hesitant to take the project on due to flaws he noted in the study’s design and recruiting methods. A pool of respondents already in poverty would not provide an accurate representation of how people became poor, he felt. To generate an unbiased sample, Morgan knew, you needed a representation of Americans from all income brackets. Researchers would then be able to track who fell into poverty, what caused the hardships, and who made their way out of economic strife.

With a new design in place, the survey came under Morgan’s direction. He and a team of researchers targeted 5,000 American families, tracking their lives as they bloomed, fractured, grew richer, and grew poorer.

And from this, the Panel Study of Income Dynamics (PSID), the longest-running and most complete portrait of the economics of the American family, was born.

Here’s to 50 — and beyond

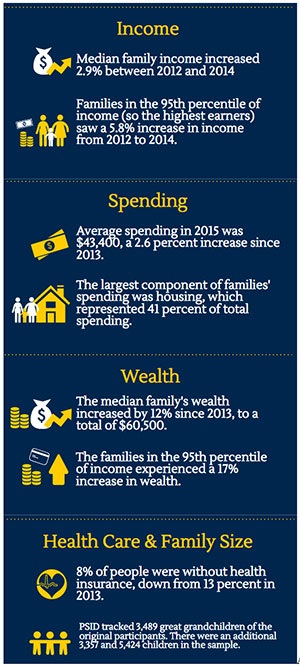

As the way Americans spent money changed over the years, so did the study. Since 1968, PSID researchers have tracked the birth and rise of buying on credit, the flood of women into the workforce, the wealth boom of the dot-com bubble, the mortgage crisis and its fallout, and now, the growth of student loan debt. They continue to ask whether participating families have children, what their income is, whether they have health insurance, and more.

Working with families, as opposed to individuals, solved a basic research conundrum that helped ensure the PSID’s longevity.

Working with families, as opposed to individuals, solved a basic research conundrum that helped ensure the PSID’s longevity.

“We decided if we follow the kids as they leave the families we first interviewed, we would have a self-sustaining national sample,” says Frank Stafford, PhD. He was a 25-year-old doctoral student when he joined the PSID foundational team. Today he is an economist in the Survey Research Center of the ISR.

Encouraging families to remain with the study over the years has been a critical component to the data’s integrity. PSID production coordinator Robin Fitzpatrick started with the study in 1982 as an energetic boots-on-the-ground leader and interviewer. Now she oversees all interview teams in one half of the U.S.

Fitzpatrick knew she had to be delicate when broaching sensitive topics — asking families about successes that lifted them out of poverty, or job loss and other crises that threatened their security.

“We’re very proactive about respect and understanding,” she says.

Fitzpatrick now trains other interviewers to follow her example, and the method seems to be working. The study’s re-interview rate over 2014 and 2015 was 93 percent — which included contacting people who didn’t respond in previous waves of data collection.

“We know we can’t replace a respondent with someone else, and we know the value of a longitudinal study is to have that constant thread of information about that person and that family,” Fitzpatrick says. “It’s like reading a great book, but chapters six through 10 are missing. If you have data on a family for the first five waves, then you skip waves six and seven, you’re missing a huge chunk of that family’s story.”

Through anonymous feedback, participants say continuing the study is as important to them as it seems to the researchers.

“Our family has been in the study for 40 years and we have an obligation to continue,” one respondent said.

Others want their economic situation to help shape the understanding of living in poverty: “It’s important to let people know how hard it is out there.”

Said another: “It’s about how we survive.”

In the beginning

In addition to Morgan and Stafford, the early PSID team included George Katona from U-M, and James D. Smith, the Office of Economic Opportunity researcher who brought the original study to ISR and Morgan.

When they presented their initial findings to the American Economic Association in the late ’60s, the results contradicted some long-held beliefs about poverty.

The big finding right off the bat? “We were showing lots of transitions in and out of poverty,” says Stafford. “That was the headline: There was lots of mobility into and out of poverty.”

Writes Greg Duncan, now at the University of California, Irvine, in a remembrance of his years with the study: “We speak easily of ‘the poor’ as if they were an ever-present and unchanging group . . . there was a huge gap between popular phenomena and the data’s clear message of turbulence and mobility.”

Creating a foundation

Studying multiple generations of families has allowed researchers to track the impact of evolving trends.

The 1970s saw an influx of American women entering the workforce so PSID researchers adjusted the questionnaire accordingly. In 1990, the study added a sample of just over 2,000 Latino households. (These households were dropped in 1995, but another sample of immigrant families was added in 1997.)

In the 1990s, the PSID responded to budget cuts by collecting data every other year, instead of annually.

In 2014, researchers collected saliva samples for genotyping, and in 2015, they began collecting same-sex marriage information.

Technology has since entered the equation with interviewers and participants sometimes corresponding via cell phone, email, and text.

The family budget

The PSID has faced its own economic stress over the decades. When its original five years were ending, President Richard Nixon cut the Office of Economic Opportunity, but luckily the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare — and now the Department of Health and Human Services — folded the study under its office’s wing.

The National Science Foundation, the Department of Labor, the National Institute on Aging, and the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development also have contributed financial support over the years, which allowed the PSID to develop its unique, multigenerational focus.“The multigenerational aspect is one of the most important parts of the study,” says current PSID director David Johnson, a research professor in the Survey Research Center. “We can follow kids who grew up with specific types of government programs or in a school district that has been desegregated. We can follow the influence of their parents and their grandparents on their well-being.”

For Morgan, who is now close to 100, the study also reveals something interesting about the definition of a family — namely, that the idea of family is fluid.

“Families keep changing over time,” he says. “They dissolve, they re-form. Marriages end. Divorces happen. New spouses come into people’s lives. Separations, divorces, births, and deaths affect the fortunes and composition of families.”

Accolades and impact

In 2000, the PSID was named the National Science Foundation’s “Nifty 50,” the only study in the state of Michigan to receive the honor, alongside innovations such as American Sign Language, MRIs, nanotechnology, and the internet. Ten years later, the study was included in the National Science Foundation’s list of “Sensational Sixty.”

In addition, James Heckman, a PSID board member and an economist at the University of Chicago, won a Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences for research he conducted using PSID data. Economist and former PSID board member Angus Deaton won the Nobel in 2015. As of 2017, PSID data has been used for 4,700 peer-reviewed journal articles and more than 800 doctoral dissertations.

This impact speaks to Morgan’s original vision for the PSID study: to make its data open and available to any researcher who wanted to use it.

“The PSID has lasted,” he says, “because we collect data about real problems and make it available to everyone.”

Horst Peppel - 1969

I remember working on Region V Survey under Michigan Crippled Children Auspices 50 years ago. My job was to meet families in the hospitals after they had been given a diagnosis for illnesses, and set up interview times in their homes. I rode my 1965 BSA motorcycle with a big yellow M on it during some interesting times and in neighborhoods that were turbulent. I recall President Johnson saying that his greatest regret was that he may hav raised false hopes of some very poor folks, upon his decision to not run again.

Reply

Penny White - Highschool 1968

Is this the Horst Peppel who lived on Pipestone Rd next to the Payne family?

Reply