Production notes and polaroids detailing one of Matthew McConaughey’s earliest roles in Sayles’ film Lone Star. (Image courtesy of the U-M Special Collections Library.)

The excitement surrounding the arrival in September of the John Sayles Archive at the University of Michigan Special Collections Library was huge.

Now nestled among the archival materials of maverick American directors Orson Welles and Robert Altman are Sayles’ scripts, production documents, legal documents, photographs, storyboards and correspondence regarding such films as Matewan, The Brother from Another Planet, The Secret of Roan Inish, Lone Star, Eight Men Out, and more. There are personal journals and notebooks, business records and props. Also included are manuscripts of some of Sayles’ novels, short stories, and plays. The archive even showcases his uncredited work as a writer on such films as Apollo 13. To date, some 250 boxes of materials covering the full range of Sayles’ remarkable career have arrived at U-M, with more expected.

The archive signals a growing research oasis for film students, scholars, and historians who know the significance of such iconic individualists as Welles, Altman, and Sayles and who want to explore the scripts, records, and artifacts that help define and illuminate their work. Those rich possibilities were unveiled in June with “The Many Hats of Robert Altman” exhibit and symposium in the Hatcher Library Gallery. Students in the Screen Arts and Cultures course “Major Directors” curated the exhibit after using the Altman archive throughout a semester. Two dozen film artists, critics, historians, and scholars who were conversant with Altman’s work as a writer/director/producer convened at U-M for a series of panels, screenings, and other events. Kathryn Reed Altman, Altman’s wife of 37 years, was a very special participant.

An American individualist

Sayles’ 35-year career as a one-of-a-kind, fully immersed independent filmmaker has been a prolific one and it continues to this day. His 18th film as writer-director, Go for Sisters, was released in limited distribution this month. It carries forth Sayles’ unparalleled skill for writing tough, honest, character-oriented scripts about people caught in challenging life situations.

Sayles and longtime producing partner Maggie Renzi on location during Sunshine State (2002). (Image courtesy of the U-M Special Collections Library.)

Critics recognized Sayles’ talent and promise as a filmmaker very early, even as it became clear his achievements stand in sharp contrast to Hollywood’s way of thinking about what movies can and should be. His first as writer-director was 1979’s Return of the Secaucus 7 (made for $40,000) about a reunion of friends who were liberal activists during their college years. Next came 1983’s Lianna, a forthright story of an unhappily married young woman whose life takes an unexpected course when she falls in love with another woman. With just these two films to his credit, Sayles received a prized MacArthur Foundation fellowship in 1983, a substantial unrestricted monetary award given to “talented individuals who have shown extraordinary originality and dedication in their creative pursuits and a marked capacity for self-direction.”

Such astutely prescient criteria would continue to distinguish Sayles’ filmmaking career. He has remained self-directed in one original work after another, exploring provocative and wide-ranging themes: race, (The Brother from Another Planet, 1984); labor union turmoil (Matewan, 1987); inner-city politics (City of Hope, 1991); self-discovery (The Secret of Roan Inish, 1994); crime and romance in a small multicultural American town Lone Star, 1996); and political corruption (Silver City, 2004).

Sayles’ expansive writing oeuvre includes several screenplays for other directors (to help fund his own projects), as well as television scripts, music videos (for Bruce Springsteen), novels, short stories, and plays. In work after work Sayles has been widely praised for writing trenchant dialogue and creating flesh-and-blood characters, often in stories involving large groups of people. City of Hope featured 52 speaking parts. Furthermore, Sayles has been a pervasive presence in all his writer-director films—fundraising, casting, often storyboarding scenes, performing, selecting music, and editing. His films, screenplays, television work, plays, and fiction have been nominated for hundreds of awards, earning many. Given the range, depth, and variety of material from America’s foremost independent filmmaker, the John Sayles’ Archive offers scholars a plethora of research possibilities—from the creative side to the business end of independent filmmaking.

Write on

Needless to say, Sayles is a habitual, copious writer and as he develops his writing projects he always records his production ideas and thoughts in spiral notebooks. I arranged with U-M Library archivist Kathleen Dow to examine one of the box sets, randomly selected. The box put before me held 30-some notebooks containing plot and character details for Sayles’ 1991 novel Los Gusanos and for the films Apollo 13 (1995, uncredited writer), Lone Star (1996), Casa de los Babys (2003), and Silver City (2004). The script notations are free form. Plots are often laid out in brief narrative scenarios, other times in screenplay formats.

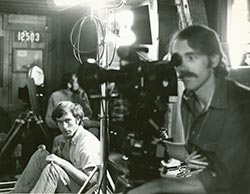

Sayles and cinematographer Austin De Besche during Return of the Secaucus 7 (1979). (Image courtesy of the U-M Special Collections Library.)

Sayles likes to jot down character descriptions as he works; for example, there’s one for each of the six female characters in Casa de los Babys, American women waiting in South America to pick up their adoptive infants. In another notebook Sayles pauses to mull over the varied American-Latino music forms he wants for the Lone Star soundtrack. Rhythm and blues, country western, gospel, bolero, conjunto will “reflect three cultures and two eras” and will offer “a rich stew of musical heritage” to reflect the Anglo-Hispanic border town, he writes. Lone Star has been praised as one of Sayles’ premier screen achievements—with the eclectic score he envisioned, composed by Mason Daring, singled out by critics for its powerful interrelationship with the film’s setting, time periods, and emotional parameters.

On reading the notebooks I felt I had crossed through a unique portal into the inner workings of Sayles’ creative modus operandi. This discernment was abetted by Sayles’ habit of including among the scripting details random, often philosophical asides about his goals as a fully committed independent filmmaker. In a note about having to suspend the making of a film, Jamie MacGillivray, due to lack of funding, Sayles leaps ahead to comment on the formative ideas for a script that would apparently become Silver City (2004), a film about a gubernatorial race in Colorado, involving a candidate from a powerful political dynasty: “Right now I’m trying to write something … that deals with the sinister power grab going on in this country, and get it on the screen before the next election.” In fact, Sayles’ thematic urges often seem fixed on stories about power control. Of the sprawling “family” of Cuban immigrants struggling to make a new life in Miami in his novel Los Gusanos, Sayles writes: “I think that Los Gusanos is about the difficulty of making choices, of knowing how to act in a world where much of the truth is hidden from them. Those in power always try to control information, to control our understanding of the situation in times of crisis.”

One of my favorite discoveries—and also a revealing one that highlights Sayles’ penchant for socio-political filmmaking—appeared in a notebook that contained eight pages of commentary in which Sayles listed and briefly critiqued some political films he found especially memorable. Some samples:

• Do the Right Thing —“Focused a national disease onto a single block”;

• Boyz n the Hood —“Allowed people into a world they didn’t know (or want to know) existed. Sometimes all aesthetic concerns are secondary to the need to throw hard light”;

• Blue Collar —“The ending is very purposely didactic, but the trip there gets into racial and class politics at a depth unmatched by few American films before or since”;

• The Accused —“The Hollywood problem-drama finally comes to grips with rape as a pervasive attitude rather than as an isolated incident.”

Sayles lists other political favorites but I’ll stop with this witty assessment of Reds: “Bohemian Romance Meets the Russian Revolution or, Why Americans Make Lousy Communists.”

My several hours spent examining just one box of Sayles’ spiral notebooks offered privileged insight into an American artist of enormous energy and commitment. My brief visit to the archive suggested a hint of what’s yet there for others to discover. The fact that the notebooks are written in Sayles’ own hand and given up for public scrutiny is in itself a remarkable gesture—a gift really. After all, at the time of their writing the recorded thoughts were private ones; now through these jotted thoughts Sayles’ creative voice can “speak” openly to us.

The John Sayles Archive is at the moment being processed and catalogued for public release. An official “opening” and celebration similar to the events held for the Altman archive are anticipated for spring 2014.