How Lynn Conway reinvented her world and ours

On a two-lane Texas highway in January 1978, it hit Lynn Conway that she might be leading a revolution.

She was 40 years old, driving a gold, wood-paneled Dodge wagon from Cambridge to Palo Alto on a southern route to stay out of the snow. She passed much of the trip with the windows down, flipping through radio stations for Boston’s latest anthem or a Gerry Rafferty saxophone riff.

The last two years had been a blur. Conway had been working for Xerox on a daring project that would democratize microchip design – break it out of the vaults of the big semiconductor firms so the “personal computers” these futurists envisioned might begin to take shape.An intensely private person, she’d spent the past semester outside her comfort zone teaching a course at MIT. She’d shown students how to design integrated circuits. And they’d succeeded. She’d even arranged for their designs to be printed in silicon – something few professionals outside the industry, let alone college seniors, had ever done.

“I knew something really wild had happened,” says Conway, now a professor emerita at Michigan Engineering. “It was, like – cosmic. It felt like I was a conduit, and the whole universe had gone through my head and come back out.”

Her trip home was also a sort of arrival. Conway had been through some false starts in her life. But on the road then, with a trunk full of handwritten lecture notes that would seed “the grand novels in silicon,” she felt she’d taken a lot of the right risks, both as a professional and as a person.

Ten years earlier, Conway had been one of the first Americans to undergo a modern gender transition. It had cost her a job and her family. Once she established herself as a woman, she kept the past a secret. Conway stayed behind the scenes as much as she could. As a result, so did many of her achievements.

Stepping into the light

She’s been called the hidden hand in what’s known as the VLSI revolution. VLSI stands for Very Large Scale Integration, and it’s the process of arranging more and more, and tinier and tinier, transistors on an integrated circuit. The movement enabled smartphones, PCs, and the very fabric of Silicon Valley – the “fabless” semiconductor firms that design chips and the “silicon foundries” that fabricate them.

In recent years, Conway’s role in all this has come into sharper focus. In 2012 editors of leading industry magazine IEEE Solid State Circuits published a special issue on her contributions. And in April of this year, the Computer History Museum in Mountain View, Calif., inducted her a fellow.

Stepping into the light – about both her gender transition and the details of her career – was a slow process for Conway. In the years since her 1998 retirement from the University of Michigan, she’s spent time writing about and reflecting on both. It has opened her eyes to some surprising parallels.

The invisible woman

Conway, 76, is tall, with light brown, shoulder-length hair and bangs that frame friendly eyes. In her ears she wears dainty gold spheres and on her wrist, a Timex Expedition. She’s a thoughtful host who sets a lovely spread of fruits and vegetables. She can also sail through mealtime meetings without eating, deep in conversation. A self-described tomboy, the hobbies of her younger years were adventure sports – exploring New England on a ’59 Harley, rock climbing in Yosemite Valley, or whitewater canoeing down Georgia’s wild Ocoee River. Those experiences still inspire her, if only as metaphor.

Conway was born in 1938 with the outward appearance of a boy. Her parents raised her that way. They didn’t understand – few did at the time – that your sense of whether you’re male or female depends on more than how your body looks. From 3 or 4 years old, Conway knew something wasn’t right. She longed for ponytails and dresses. Her parents discouraged behaviors they saw as odd.

She started looking for answers in adolescence. Her mother was studying anthropology at Columbia University and Conway got hold of some of her textbooks.

Lynn Conway, a Michigan Engineering professor emerita and advocate for transgender rights, changed the way engineers design microchips. Here, she combs her hair in her home near Jackson, Michigan. (Photo: Marcin Szczepanski.)

“It seemed like people in other cultures had found different ways to deal with what I knew I was feeling,” she says. “But then that became scrambled with the thought that what I was feeling was that I was gay, but no one ever talked about those things.”

Whatever it was, Conway knew she was facing a stigma. At the time, being transgender or homosexual was considered a mental illness, and mentally ill patients were often institutionalized. Electroshock treatments were common. Some even underwent so-called transorbital lobotomies that psychiatrists could do through the eye sockets with ice-pick-like tools.

When Conway was 14, she read a news story about former Army private Christine Jorgensen, the first person in the U.S. to publicly announce a gender transition.

“I knew then what I had to do,” Conway says.

She never questioned whether to do it. She only questioned how. Three years later, as a freshman physics student at MIT, she figured out how to get black-market estrogen. She started injecting herself and leading a double life.

The hormones began to work, but not fast enough. For a gender transition to be most effective, a person should start as early as possible. Many transgender women want to avoid the masculinization of their faces and bodies that continues past puberty, into the 20s and 30s.

Conway asked a friend in medical school if he could help her find a doctor to do surgery. The friend took her to a dean. The dean told her to stop taking hormones or she’d end up in a mental ward.

She reverted to boy mode.

A life on the edge

“While this was all going on, I was getting better and better at appearing to be and behaving like a very adventurous guy,” she says. “I’d put on my motorcycle gear and leather jacket and I could scare people, which felt really weird.”

She fell into a deep depression.

“Everything crashed and burned.”

Adventure sports have been among Conway’s hobbies since childhood. Here she rides one of her dirt bikes at the Mounds off-road vehicle park near Flint, Mich., in 1991. (Image courtesy of Conway and COE.)

Conway started hanging out with a rebellious group and going for long rides on her motorcycle.

She dropped out of MIT and moved home. She decided she would live in her mind, and dedicate her life to engineering. She enrolled at Columbia to finish school.

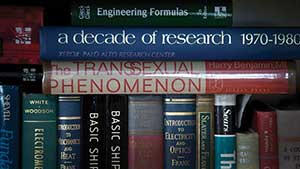

Then she read another news article. This one was about Harry Benjamin, a doctor in San Francisco working on transgender medicine. He had come up with an effective hormone regimen and was administering it along with counseling on surgical options.

“Now I had a plan to get across the river,” she says. “I could see the steps I’d have to make. I could see the dangers and how to protect against them. The only problem was, I didn’t know where I’d end up on the other side.”

Conway started saving more of the money she earned as a hearing aid repair technician. But this was a lonely time. A one-night stand with a friend left the friend pregnant.

Dr. Benjamin moved to the back of her mind. Conway got married, became a father, and landed a job at IBM. A second child was born, and for a time, the domestic life distracted her. She was ascending at IBM and the company transferred her to the Bay Area.

In her late 20s, though, Conway heard the clock ticking loudly. She started scaling higher and higher rock walls.

“This was the end game. I was running out of time to do anything about it. Climbing in the Valley was like escapism. It was like being right there on that edge.”

One night, she almost went over it. Curled up on the carpeted living room floor with a gun to her head, Conway wailed until her wife woke up.

“I couldn’t live anymore,” she says.

Her wife saved her and together they mapped next steps. They would divorce. Conway would see Dr. Benjamin. She would pay child support and stay in the children’s lives. They’d call her “aunt.”

Conway’s supervisors at IBM accepted it at first. But as medical leave approached, the top brass found out. Conway was fired.

Her employer’s change of heart had a domino effect. Fearing that social services would take the kids, Conway’s ex-spouse decided she couldn’t have any contact with them. They were 2 and 4.

“That tore me up, let me tell you.” She rolls her eyes through a deep breath. “It’s long enough ago now that I don’t get choked up, but the hardest part about the whole thing was that. I felt like a mom to them.”

“An undocumented alien from Mars”

Conway went abroad for surgery and then stayed in the home of her electrologist in San Francisco for several months. And in the fall of 1968, she started living full time as a woman.

The first thing she did was change her name. Dr. Benjamin had connections at a court in Oakland County that didn’t make a big deal out of the process. Then she got a new driver’s license. Logistics are big parts of a gender transition. Back then, they had to be navigated quickly to avoid suspicion and erase the past, however painful that might be.

Conway works at Xerox Palo Alto Research Center, also known as PARC, in 1977. From her position at PARC, Conway helped to lead the paradigm shift in microchip design known as the Very Large Scale Integration revolution.

“You were an undocumented alien from Mars,” Conway says. “You don’t have a birth certificate. How are you going to get a job? This was the ’60s. You can think of it like being a spy in a foreign country. If you were found out, you’d be dealt with immediately, if not by the police, by the people on the streets.”

She lived in “pretty much stark terror” for a year or more. This was 40 years before Time magazine would declare a transgender tipping point on its cover, which it did this summer. More trans people are finding acceptance and admiration in the public eye today, but they still face discrimination and violence. The environment was more dangerous for the pioneers. Conway speaks of a friend who was gang raped by police officers.

Despite the circumstances, Conway didn’t consider her new life a difficult one. She saw each obstacle as “a simple matter of life and death.” It reminded her of rock climbing.

“I was on an adrenaline high adventure,” she says.

To find work, her doctors connected her with a head-hunting agency. She started as a contract programmer and quickly ascended to Memorex and then to the high-profile Xerox Palo Alto Research Center.

Meanwhile, she was learning how to outwardly express the femininity she had always felt, but had to hide.

“I was a fledgling woman,” she says. “I didn’t have any social graces. Here I was a professional, presumably educated. But I really didn’t know how to dress right. I was kind of a klutz. I was shy.”

Bert Sutherland was her manager at Xerox.

“She was very introverted, circumspect,” Sutherland says. “Nobody knew anything about her. It was like she came to work and then vanished.”

Conway honed her “spycraft.” She learned how to watch a room and spot threats, how to read other people’s faces for signs she was misstepping, how to hide fear and dodge questions. She also made herself scarce, at least among her co-workers. That was the easiest solution.

The microchip revolution begins

In the early 1970s, Intel released its first single-chip microprocessor, and industry leaders knew it held great promise.

Cal Tech professor Carver Mead had recently coined the term Moore’s Law for the prediction that the number of transistors on a chip, and with that, computing power, would double every two years. But at the time, chip design happened only inside big semiconductor firms like Intel. That meant computer engineers, like those at Xerox, couldn’t start from scratch. To make their machines, they’d order components that arrived with information about how they worked.“It was like Lego sets,” Sutherland says.

Xerox wanted to know how to design chips itself. Sutherland put Conway on the project and brought in Mead to work as a consultant.

Conway had experience making computers. Back at IBM, before she was fired, she had invented a hardware protocol called dynamic instruction scheduling that enabled the out-of-order command processing most computers use today.

But she didn’t know how to make microchips. So she learned. Then she ignored most of what she absorbed. Conway and Mead felt the process needed to be reimagined, standardized, and simplified.

“I could envision that it could be like opening up Impressionism,” Conway says. “All kinds of people who could never paint well in the old way could then figure out how to do something new, impressionistically. And they could say things none of the other people knew how to say.”

“I could envision that it could be like opening up Impressionism,” Conway says. “All kinds of people who could never paint well in the old way could then figure out how to do something new, impressionistically. And they could say things none of the other people knew how to say.”

Conway worked six or seven days a week, sometimes 12- and 16-hour days. She distilled the chip layout process into two pages of rules that a novice engineer could understand. She built the rules around ratios of dimensions rather than specific dimensions, and because of that, they have remained relevant through the decades as chips have shrunk.

Sutherland liked what they’d done, but the ideas were so radical, they would need help catching on.

“What if we do a book?” Conway remembers suggesting.

A textbook would take the new concepts straight to the next generation. The team began writing Introduction to VLSI Systems and self-published the early versions at Xerox.

“The book was a landmark,” Chuck House, director of InnovaScapes Institute wrote in the IEEE special issue about Conway. “The paradigm shift that enabled Apple’s and Microsoft’s emergence had vital antecedents that have largely remained obscure. Conway’s role there, while crucial, has often seemed behind the scenes to outside observers.”

The seeds of Silicon Valley

With their book in hand, the team decided to pilot a hands-on course at MIT. Sutherland insisted that Conway teach it. But Conway didn’t want the job. Go back to MIT – the place she left despondent in her teens? Stand in front of a class of judging students who might think her voice sounded off?

“So much was at stake,” Conway says. “I was so frightened.”

For weeks, she mulled it over. Then she packed the Dodge and headed east.

To increase her odds of success, Conway over-prepared.

In 1978 at MIT, Conway taught a seminal class on microchip design. In it, students designed their own microchips for the first time. This is an image of the multiproject chip set design that Conway sent off to industry to be manufactured. (Photo: Marcin Szczepanski)

“This was like planning a military campaign,” she says. “There was so much that had to work, just precisely. By the time I got to class, it was like: OK, we’ve got to do this today. You have to learn this now. Time is passing.”

Students described the atmosphere as creative and different.

Before the holiday break, Conway used the primitive Internet known as Arpanet to get the designs to industry to be manufactured. In January, chips arrived in Cambridge.

“When we got those projects back and they mostly worked, it was clear this was going to go gangbusters,” Sutherland says.

An exhilarated Conway set off home. She stopped at her mother’s grave in Texas. She shared a sandwich with a stray dog near the side of the road. And she imagined the possibilities for the work she’d just finished. Or was it that she’d just begun?

The following year, as the book’s popularity grew and universities across the country offered similar classes, Conway made a controversial promise, on Xerox’s behalf, to get semiconductor firms to make the prototype for each student’s project. She planned to use the Arpanet again. It would be an early e-commerce system.

It worked. In the fall, files from 12 universities “surged across the Arpanet,” Conway wrote.

Randal Bryant took the course at MIT in 1978 when he was looking for a PhD thesis topic. He found one, and spent the next decade on VLSI design. Now, he’s a university professor of computer science at Carnegie Mellon.

“The course opened up an entirely new technical discipline for me,” he says.

Hundreds, and then thousands of students like him were trained in the Mead-Conway method. They made posters of their designs, called check plots, and hung them on their office walls. The posters looked like cityscapes. As the years went on, they seemed to be taken from higher and higher vantage points as chip components shrunk and computing power exploded. The students launched startups and research labs. Silicon Valley earned its name.

The quiet child

While all this was happening on the coasts, Conway accepted an invitation to come to Michigan Engineering, which was launching its own program in VLSI design. Though she never had earned a PhD, college leaders appointed her professor and associate dean for instruction and instructional technology.

“She helped us get the joint jumping,” says Dan Atkins, W.K. Kellogg Professor of Community Information and professor of electrical engineering and computer sciences who was then an associate dean.It was in Michigan that Conway met her husband, a fellow canoeist. They settled on 23 acres near Jackson. Here, she also reunited with her daughters, but only briefly.

As the new millennium and Conway’s retirement approached, so did the end to her stealth mode. She began to see signs online that others were taking credit for the IBM work she had done under a different name. To correct the record, she would have to tell her secret. No one except those closest to her knew.

Conway first told the computer historian whose work had tipped her off about the IBM discrepancy. Then she simply added a “gender transition” section to her website. So began the next phase of her life – as an outspoken advocate for transgender rights. She is still involved in this effort.

Today, she finds joy in tending to the nature preserve she calls home. She and her husband have transformed it over two decades from a cornfield to what Conway calls their “playground.”

Through the hundreds of native trees they planted and across log trails they built, they go for long walks every evening. On a hilltop bench on the far west edge, they watch the sun set.

Conway has spent a lot of time deconstructing how she’s been able to engineer change in her own life and the world around her. She’s written long, hyperlinked memoirs. But it seems to boil down to something simple.

“A lot of it has to do with learning how to do new things – how to not be afraid to be a beginner, to just be kind of a quiet child and just observe,” she says.

“And then, it’s kind of like, ‘Why not question everything?'”

Daniel Olson - 1980

Thanks for the story. And more thanks to Ms. Conway. Progress depends on someone taking action like you did.

Reply

Nancie Stoddard - 1981

You’re a brave woman and I admire your tenacity!

Reply