“The deed is done.”

Tappan announces news of the Civil War from a makeshift stage in downtown Ann Arbor. See larger image, courtesy of U-M’s Bentley Historical Library.

On the evening of Saturday, April 13, 1861, President Henry Philip Tappan looked in at the office of the Argus,Ann Arbor’s daily newspaper. Momentous news was coming in by telegraph: The day before, in the harbor of Charleston, S.C., soldiers of the newly declared Confederate States of America had begun to bombard forces of the federal government inside the offshore fortifications called Fort Sumter. A civil war, feared for months, had begun.

At chapel services on campus the next morning, Tappan said he would address a mass meeting at 3 p.m. in the courthouse square at Main and Huron. Students pounded together a makeshift platform.

Until now, as a public figure who needed to stay aloof from politics, Tappan had muffled his pro-Lincoln, anti-southern sentiments. But things had changed.

“Friends,” he told his listeners, including hundreds of Michigan students, “the deed is done. . .Let us look into our own faces. The nation’s future lies with us.”

The Union must be saved, he said, however long and deadly the struggle might be.

“Earnest, impressive and thrilling as he usually was on the platform, Dr. Tappan was infinitely more so on this occasion,” a witness wrote. “His address. . .aroused to even greater ardor the patriotism of the young men, and made an everlasting impression on every heart.”

Call to arms

The next day, President Lincoln issued a call for 75,000 volunteers to put down the rebellion. But when students told Tappan they meant to go, he urged them to stay until the semester’s end, then disperse to their homes to sign up there. They got the same advice from Andrew Dickson White, the young professor of history who was a favorite of the students.

“Wait,” White told them. “This is not to be a war of months, but years. You will have your chance. Finish your course.”

A few left to join the First Michigan Infantry, which fought soon at the first battle of Bull Run. But most of them stayed, trudging to class every day, keyed up and nervous. Professors took pity on them. “Slips in Greek and Latin, history and philosophy, were kindly disregarded,” one of them recalled.

A love of liberty

See larger image, courtesy of U-M’s Bentley Historical Library.

In 1861, Ann Arbor was a village of about 5,000. The streets bordering the Diag were dusty clay on dry days, muddy clay when it rained. Only 25 years earlier the 40-acre campus had been a farm, but now, long lines of elm seedlings were starting to flourish, thanks to Professor White, who was waging a tree-planting campaign in spare hours and on his own dime.

Students at U-M numbered about 640, all of them male. In the class of ’61 there was only a handful of southerners. Most of the rest were from Michigan and her immediate neighbors. “There were some good hunters and rifle-shots,” recalled one of them, William Beadle. “They were of the stuff of the then new West, were physically vigorous, and generally felt an inheritance of individual liberty and love of free speech.”

For most of these northern boys, Beadle said, the love of liberty stopped short of support for enslaved black workers on southern plantations. Like the new Republican Party, most of them only opposed the extension of slavery to the western territories. They were willing to tolerate slavery in the old South if that was what it took to prevent southern secession.

A small, secret circle of Ann Arborites were helping fugitive slaves get to Canada. But many U-M students saw abolitionists as dangerous radicals — “roving, crazy fanatics,” as the Argusput it. When the abolitionists Josephine Griffing and Parker Pillsbury came to town on their circuit of the western states, a mob stormed the church where they were speaking and chased them out.

A cry to crush secession

In the winter of 1861, the public mood, already tense, had grown deeply anxious. As the Republican Abraham Lincoln prepared to take the oath as president, southern states responded by declaring their independence one by one.

On the U-M campus, as elsewhere in the north, the attack on Sumter brought a near-unanimous cry to crush secession. When a patriotic singer draped herself in the flag at Hangsterfer’s Saloon and belted out “The Star-Spangled Banner,” the crowd — most of them students — insisted she repeat the performance every night for a week.

At sunrise on Monday, April 29, two weeks after the Sumter attack, 75 members of the Steuben Guards, Ann Arbor’s militia, gathered to leave for training camp. Nearly the whole town came out to see them off. Each volunteer was given a New Testament, and their commanding officer was presented with a new revolver. Three cheers rang out for the Guards, then three more for the Union.

Company men

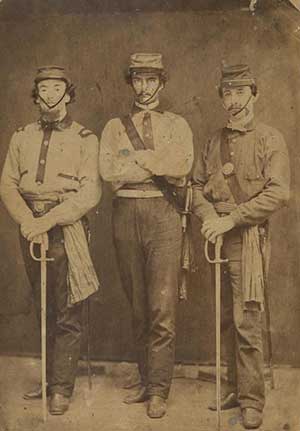

Captain Charles Kendall Adams, ’61, Captain Isaac Elliott, ’61, and Captain Albert Nye, ’62. See larger image, courtesy of U-M’s Bentley Historical Library.

Acting on their own, students had already organized three companies of volunteers for training and drills. They called themselves the Chancellor Greys, under Captain Isaac Elliott,’61 (the name honored Tappan, who used the title “chancellor”); the Ellsworth Zouaves, under Captain Albert Nye, ’62; and the University Guards, under Captain Charles Kendall Adams, ’61. (Adams was then earning his room and board as headwaiter at a local boarding house. He would later join the U-M faculty as a history professor, and he wound up as president of Cornell University.)

In the morning, the companies would drill on the field between Haven Hall and South College, about where Angell Hall is now, or in a long, vacant room on the first floor of South College. At noon they would march up to the northwest gate at State Street and North University and on through town.

One evening they marched past the house on North University where Professor White lived. According to one in the company, who said his report was verbatim,the young professor said: “Young gentlemen, you are engaged in a righteous cause. This is a conflict between twenty-two millions and ten millions, between freedom and slavery, between God and the devil! In such a contest you cannot fail!”

Finally, near the end of June, Commencement arrived. During the ceremony (uptown at the Methodist-Episcopal Church), President Tappan called the roll of seniors, pausing after each name to add, in Latin: “Ascendat!” (“Rise!”) Each graduate rose and received his diploma. Then they joined in a song that was spreading through the northern states, “The Boys of ’61.”

Do you hear the fife and drum

calling us to come

Come and join the comrades

that have gone before?

Gone, but not forgotten

More than half the graduates of 1861 were enlisted by the end of that summer. Figures vary as to the total number of U-M students who served in the Civil War, from 1,440 to 1,804. Roughly 110 died in the conflict, from Gettysburg in the east to Shiloh and Vicksburg in the west, including one of those volunteer captains of 1861, Albert Nye, who was killed in 1862 at Murfreesboro, Tenn.

Decades later, in old age, Andrew Dickson White had an impulse to visit the Michigan campus. Before the war was over, he had returned to his home state of New York, where he, like Charles Kendall Adams, had become president of Cornell.

A student recognized him as he walked among the elms he had planted on the Diag. Asked what he was doing, White replied:

“Yesterday, while sitting in my library in Ithaca, I happened to think that fifty years ago today the class of 1861 planted these trees under my direction. I had among my papers a plot of the ground, the location of each tree, and the name of the student who planted it.

“There are more trees alive than boys.”

Sources included: Isaac H. Elliott, “Some of the Boys of ’57-’61” and William H. Beadle, “Ascendat!” Michigan Alumnus (March 1903); “Departure Of The Steuben Guards,” Michigan Argus, 5/3/1861; James Tobin, “Ann Arbor Abolitionists,” Michigan Today, 2/10/2009; “Professor White’s Diag,” U-M Heritage Project; Howard Peckham, edited and updated by Margaret L. and Nicholas H. Steneck, The Making of the University of Michigan, 1817-1992 (1967, 1994); Kent Sagendorph, Michigan: The Story of the University (1948).

Top image courtesy of U-M’s Bentley Historical Library.

Jeff Dulzo - 1981

Based on this part of the article that says, “When the abolitionists Josephine Griffing and Parker Pillsbury came to town on their circuit of the western states, a mob stormed the church where they were speaking and chased them out.”, there were at least some who opposed with the war. Did the “Boys of 61” chase down these dissenters in Ann Arbor, because they opposed the war?

Reply

James Tobin - 1978, 1979, 1986

The ones who opposed Griffing and Pillsbury were pro-Union types who nonetheless thought abolitionists were endangering the Union with their die-hard anti-slavery stance. So we don’t know how the U-M “Boys of ’61” felt about that fracas. Probably there were some who were for the abolitionists and some who were against. The key thing to understand is many northerners went to war with the South not so much to end slavery as to restore the Union. That’s one of the reasons why Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation (which freed the slaves ONLY in areas under Union control) was controversial even in the North. Here’s an earlier story in Michigan Today that deals with the incident in a little more depth: http://michigantoday.umichsites.org/a7347/

Reply

Carl Stein - 1982

The Emancipation Proclamation freed slaves only in states that were in rebellion against the Union on 1 January 1863 (not in states or parts of states that were under Union control at that time). https://www.abrahamlincolnonline.org/lincoln/speeches/emancipate.htm

Reply

Paul Trame - 65 / 67

Terrific story. Good view of the times.

Reply

Tom Collier - 0000

An important story well told, with a moving and memorable ending.

Reply

Gregory Smith - M.S., Mathematics, 1961

My great-grandfather Dr. Amos Kendall Smith enlisted for three years in the Army on 15-Sep-1861 at Ann Arbor as a Pvt. in company I, 1st Michigan Cavalry Regiment. He was a 19 year old medical student from New York State. He served several years, obtained an M.D. from City College of New York while enlisted and became Surgeon Major of the 1st Michigan Cavalry.

Reply