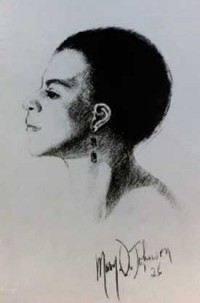

Lenoir Bertrice Smith as drawn by Mary Johnson. (Image courtesy of the Joseph A. Labadie Collection, U-M Special Collections Library.)

It began at the lunch hour one day in the fall of 1925, a time when there were perhaps 60 black students out of 10,000 at the University of Michigan.

That day an African-American student named Lenoir Bertrice Smith had only a short break between classes near the Diag. There was no time to run home for lunch, and she hadn’t brought anything to eat. So she and a white friend, Edith Kaplan, went into a restaurant by Nickels Arcade and sat down for a quick bite.

They waited.

Finally a bus boy came to their table and set a pile of dirty dishes on the table between them.

Smith looked at the dishes, then rose from her seat.

Before arriving at U-M, Kaplan had never spent time with black people, so it took her a moment to understand what was happening. Then she looked at Smith, and “trembled with rage when I saw her face,” Kaplan recalled long afterward, “and I knew that the dirty dishes had not been accidental.”

“Correct, cold, and unsympathetic”

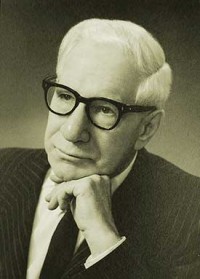

The two women went to see Oakley Johnson, a young instructor in the Department of Rhetoric. Smith was enrolled in Johnson’s class and knew he was sympathetic to the situation of black students. The women asked him what might be done.

Johnson took them to see John R. Effinger, dean of the College of Literature, Science, and the Arts. They hoped Effinger might bring the University’s influence to bear on Ann Arbor restaurant owners who refused service to African-American students.

According to Johnson, Effinger’s response was “correct, cold, and unsympathetic.”

“Why, I’m very sorry about this,” Johnson recalled Effinger saying, “but, you know, the University has no control over the businessmen of the city. Our domain ends at the edge of the campus. We can’t do anything at all.”

“But can’t you express the University’s desire that its students be treated properly?” Johnson implored. “After all, they’re students here, regardless of color.”

“No,” Effinger said. “My grandfather owned slaves in Virginia, but you mustn’t think I’m prejudiced. I would do something for you if I could.”

“He seemed to think we were demented,” Johnson recalled.

So the students and Johnson decided to do something for themselves. They recruited other students — mostly African-Americans but also a number of whites – and declared themselves the Negro-Caucasian Club of the University of Michigan. It may have been the first such group on any American college campus.

If not demented, they were certainly audacious.

“Not part and parcel of the school”

The first two African-American students had been admitted to U-M in 1868. But only a handful followed, and by the 1920s, blacks still comprised just a tiny fragment of the student body. By University practice and informal understandings, they lived in a segregated sphere, joining white students only in classrooms.

In that era only women lived in University dormitories – but not the six or seven black women enrolled at U-M. They lived in a boarding house arranged by the University. African-American men lived in one of three black fraternity houses, or boarded with black families. They were not served at the Michigan Union, nor were they allowed into University swimming pools or University-sponsored dances.

“The colored were not part and parcel of the school,” recalled Joseph Leon Langhorne, a black graduate of 1928.

In this atmosphere, the Negro-Caucasian Club sought approval as an official student organization. It was hard to come by.

This image from the 1927 Michiganensian, showcases the founding members of the Negro-Caucasian club. (Image courtesy of U-M’s Bentley Historical Library,)

The faculty senate’s Committee on Student Affairs recognized the group as an official student organization for only one year, and only on two conditions: It must drop its stated purpose of working “for the abolition of discrimination against Negroes,” and “the name of the University of Michigan shall not be used in connection with the activities of the Club.”

With that cold send-off, the club began. Johnson served as faculty adviser.

Down to business

One of the organization’s first activities was to distribute 100 surveys to white students with such questions as: “How many Negroes have you met other than your maid or butler?” and such true-or-false choices as: “All Negro men are drooling for the chance to rape white women.” The responses, tabulated by sympathizers in the Department of Sociology, were predictably dismaying.

“We concluded that the problem was one of belief in the sub-humanity of Negroes and unfamiliarity,” Smith recalled later. “On this basis we decided to bring outstanding Negroes to the campus to show people that there were Negroes who were not ‘hewers of wood and carriers of water.’”

Distinguished lineup

The first to be invited was the African-American philosopher Alain LeRoy Locke, a key figure in the black cultural awakening known as the Harlem Renaissance. Locke’s address in the then-new Natural Science Building had the intended effect among white students. Julius Watson, a black student from Detroit, remembered the reaction of a white teacher from Arkansas who was attending graduate school at U-M. “After [Locke’s] talk someone asked her if she was surprised,” Watson said, “and she remarked that she was really shocked because she did not dream that there was a Negro who could say so many things that she could not understand.”

More speakers came, including the great activist and writer W.E.B. DuBois and the novelist Jean Toomer. Members of the club met with A. Philip Randolph, the labor leader who would organize the first march on Washington for civil rights; Frank Murphy, the liberal Detroit judge who would later defend minority rights as a U.S. Supreme Court justice; and Clarence Darrow, the fiery criminal lawyer who defended the black Detroit physician Ossian Sweet in the most celebrated civil rights trial of the era.Johnson, who was not only a champion of civil rights but a Marxist and a member of the Communist Party, left U-M in 1928, his bid for tenure denied despite the backing of his department. The Negro-Caucasian Club continued until 1930 with another faculty adviser, then faded as the Great Depression took hold.

The members went their separate ways, many to distinguished careers. Because of her experience in the club, Sarita Davis gave up her plan to become a missionary abroad and instead became a social worker in the U.S. Lenoir Bertrice Smith — now Lenoir Smith Stewart — came back to Michigan for a master’s degree in the 1930s; from 1953-58 she was head of the serology section at University Hospital. K.T. Harden became dean of the medical school at Howard University. Armistead Pride became the longtime chair of journalism at the historically black Lincoln University. Edith Kaplan Ritter became an authority on ancient languages at the University of Chicago.

“We had ideas, feelings, aspirations”

In 1969 club alumni gathered in Washington, D.C., for a reunion. Looking back at their time in Ann Arbor, what they remembered most were their own informal gatherings, usually at 620 Church St., the home of Oakley Johnson and his wife, Mary.“We sat on the floor and talked and ate peanuts,” Lenoir Smith Stewart remembered. “We tried not to discuss the Race Problem, but everything else, in order to prove that we could – that we were not sub-human, that we had ideas, feelings, and aspirations.”

“The Negro-Caucasian Club at Michigan helped relieve the Negro student’s feeling of isolation,” wrote Armistead Pride, “and to give him some portholes onto campus life other than those of the classroom and the Michigan Daily.”

“For many of us this represented the first social contact with Caucasians which was of more than a casual degree,” wrote K.A. Harden.

White members remembered a fundamental change in their outlook.

“Because of those associations, I lost my black-white feelings,” Davis recalled. “Ever since, a Negro has been another human being to me.”

Sources included the papers of Oakley Johnson in the Joseph Labadie Collection, Special Collections, Hatcher Graduate Library; and Oakley Johnson, “The Negro-Caucasian Club: A History,” Michigan Quarterly Review (Spring 1969).

Richard Brouwer - 1962, School of Social Work

How do I respond? With shame at the unspeakable bigotry hosted and abetted by my alma mater? Yes, but also with pride and a sense of encouragement that my alma mater has the integrity to acknowledge this sordid part of its history and expose it to the world. There is something redemptive about that and I congratulate the author and those responsible for presenting this piece.

Reply

James Tobin - 1978, 1986

Mr. Brouwer: You just made my day. No…my week. James Tobin

Reply

lewis(Bill) Dickens - 1964

With the recent decline in Black Student enrollment by 50% it’s clear that the University has not advanced at all and has been in eclipse.

Now 50 years after my graduation and my reading of the Great Society Speech over LBJ’s shoulder, this Presidential Speech, ranked somewhere in the mid 50% of the all time great Presidential Speeches was ignored if not suppressed. There was no such foofaraw as there was about the Peace Corps Speech which lead to the birth of President Obama.

Clearly, the recent Administration and outrageous board of Governors have lost course. Let us pray that the ship can be righted otherwise the University will lead us nowhere and become the shame of the Great State of Michigan and despoil the great works of Michiganians, Michiganensians, and Michigensians past.

Reply

James Daugherty - 1971

This was an enlightening article. I recall the Federal Civil Rights Act of 1964 being passed (when I was a high school freshman) 50 years ago and the controversy surrounding it. Now I wonder how this was not passed until 1964, given the racial environment of our country in the 50’s. I can only imagine the formation of this club in 1925 with a total of 60 African-American students at UM and the overwhelming resistance they encountered.

Reply

Kevin Atkins

The description of the callousness and disregard by the dean is interesting to contemplate with the knowledge of how currently campus administrations around the country treat the latest disfavored group of students – those with classical-liberal political ideals and/or traditional values. The wheel turns with regard to who is on top, but the results are always the same for whomever is the ‘out’ group of the time. The interesting thing of today is the intolerance exhibited by those who claim to value tolerance.

Reply

Paul Kirby - 1967

It is highly regrettable that so much racism has permeated the history of my alma mater, of which, in many other aspects, I am very proud. However regretful we are of the past (including the most recent past), it is highly important that we think in a forward direction and take what Abraham Lincoln called “increased devotion” that our future should be one of complete recognition of the unity of the human race and understanding of the inclusiveness of all races, religions, genders, sexual orientations, and any other factors that could cause division. “A house divided against itself cannot stand.” We have more than enough external enemies; we do not need internal division.

This comment should not be read to imply that efforts to increase minority enrollment are unnecessary or undesirable because all we need to do is feel unified as human beings. If any part of humanity is being held back by external factors, it is an assault on all human beings, and it needs to be fixed. We definitely need to improve conditions in minority neighborhoods, including better educational opportunities, as well as protection from crime and from low expectations. Instead of endlessly arguing in our legislative bodies about the value of various programs, it would make more sense to have a serious dialogue between the advocates for improving minority neighborhoods and the legislators who have the power to allocate resources, find some common ground, and start moving forward.

Reply

Fred T Black

Not an Alumni, but I have Family that are Alumni, and Family employed by U of M.

My comment:

THANK YOU

Reply

Carmen Shamwell - 2003

Such an amazing and well-written article. I love reading about my Alma Mater’s past and as a minority student, this one certainly hit home.

Reply

Sandra Keene - AB 1971; AM 1976

Wow. Amazing article. How sad that so much has not changed enough. My husband and I probably would have joined the Negro-Caucasian Club had it existed when we were there. We met in 1969 when we both lived in South Quad. He was in pre-Med and later graduated from Med School and did his residency in OB/GYN at University Hospital. We married in 1971 and lived in Ann Arbor until 1978, when we moved to California. U of M was a wonderful, safe, supportive environment for us and our relationship. An oasis, so to speak, during some turbulent times. May Michigan continue to be as wonderful for today’s students as it was for us. We surely need to learn how special we ALL are.

Reply

Jeanne Seals - 1959

Many thanks to Mr. Tobin for this informative article. I am heartened by our out going President Coleman’s efforts to increase financial aid to minority students, as well as others, and her efforts to make diversity part of a student’s experience at this esteemed University. I hope that there are more Professor Johnsons on the present faculty to support these efforts.

Reply

Mike Mosher - UM faculty (1957-76) brat & alumna's spouse

An informative article, with both villains and heroes. Thanks for researching this aspect of UM’s & Ann Arbor’s history.

I was visiting a friend in the hospital, and enjoyed all the photos of the UM Medical School’s graduates over the years. The first African American graduate was apparently a Dr. Robinson in the class of 1930. I notice he wasn’t in the Negro-Caucasian Club. I’d like to learn more about him, and his career and practice (in Michigan?) after graduation.

Reply

Richard Smith - 1973

Great review, one glaring omission however: the Epsilon Chapter of Alpha Phi Alpha Fraternity was founded at the University of Michigan in 1909. The Chapter in fact remains a strong positive presence on UM campus and predates even the national organizations of both the other fraternities mentioned in the article. At the time of the establishment of the Negro-Caucasian Club, the Alpha fraternity house was at 1103 E Huron (the site of today’s Power Center). Furthermore one of the founders of NCC, Joseph L. Langhorne, 1103 E. Huron was an Alpha as well as Dr. W.E.B. Dubois who was initiated into the Alpha Phi Alpha Fraternity at the University of Michigan and frequently lectured in Ann Arbor. Another notable point, Robert Syphax’s relative, Gregory Syphax was an All-American at Michigan in the 1970s

Finally my question for the author, is W. G. Bergman the same Dr. Bergman who as a Freedom Rider in the 1960s was brutally beaten by the KKK?

R Smith, MD UM’73

Reply

Anne Wolfe - 1980

While I can echo that it is shocking how many were treated, and heartening that these brave people struck out on their own to form a positive alliance, I must note how very important it is that the truth – the bad, good and ugly, be preserved for exactly what it is, not changed, or tempered with any shredder or revision. In this way we can look at ourselves unflinchingly, reflect at not just who we are, but who we were, who we still are, and then decide where we want to go. U of M can be commended for preserving so much of its real past.

Reply

Melba Joyce Boyd - 1979, Doctor of Arts, English

As an African American Studies scholar and professor, this experience is not news to me, and for the most part is reflective of the treatment black students experienced at mainstream colleges and universities during this period. What amazes me is that so many people have little or no knowledge of widespread discrimination that affected students at this time, and their careers upon graduation. In 1990, during the recognition of the 20th anniversary of the Black Action Movement at UM, significant research on the history of race at UM was revealed and documented by faculty and scholars affiliated with the university. This document was published and is available in the university’s library.

Reply

Lanie Dixon - B.S.E. Industrial and Operations Engineering 2001

“We tried not to discuss the Race Problem, but everything else, in order to prove that we could – that we were not sub-human, that we had ideas, feelings, and aspirations.”

Thank you for this poignant glimpse into my alma mater’s history. I can’t put words together that can convey the gravity with which this hit home for me.

Reply

Inger Kent - 1991

Bravo for this slice of history and pride. Being first in stepping out to confront a problem with a solution should always be celebrated. I’m sharing this article with friends. Thank you!

Reply

Katherine Mendeloff - Not a UM grad- but on faculty since 1990

I am very intrigued by the article and hope to learn more about the dynamics of this important group. I am a Drama faculty member at the Residential College and helped produce a play based on the stories of the first co-eds at UM in the early 1870’s. Now, the School of Social Work has commissioned a play for the 100th anniversary of the school’s founding. Our focus will be the African American graduates of the SSW during the early decades of the 20th century, and the impact their work had on building social service institutions in Detroit.

If anyone has more information about these years, please contact me at mendelof@umich.edu. We will be working with research material to create scenes and monologues to be performed in November, 2021.

Reply