In this month’s Health Yourself Victor Katch discusses lipids (from the Greek lipos, meaning fat). Katch has produced a basic primer on dietary fat, examining different kinds of lipids, their origins, and their role in the body. He discusses the influence of dietary fat in the foods we consume, and takes a look at the ongoing controversy regarding how much and what kind of fat you should be eating to “health yourself.”

In last month’s column I discussed the ins-and-outs of proteins. One of the important points was that the average adult requires a minimum daily amount of protein (about 0.8 grams per kg of body weight) for optimal health.

While there is no required minimum fat or carbohydrate requirement, there are recommendations for average intake levels (based on body weight or total calorie intake) to promote optimal health. Of course, controversy often accompanies these recommendations. Hucksters are quick to exploit any uncertainties introduced by science in the interest of selling their products.Ever since scientists began to study the relationship between food consumption and the development of chronic disease, systematic findings have pointed to a causal link between consumption of certain lipids and disease risk. Ongoing research and new discoveries about different types of fat continue to reinforce that link, principally in the area of cardiovascular disease.

Dietary fats: The good, the bad, and the confused

Lipids are generally greasy to the touch and insoluble in water. They share identical structural elements with carbohydrates, but differ in their linkage and number of atoms. Specifically, lipids’ ratio of hydrogen-to-oxygen considerably exceeds that of carbohydrate. For example, the formula C57 H110O6 describes the common lipid “stearin,” a saturated fatty acid with a hydrogen-to-oxygen ratio of 18.3:1. For carbohydrate, the hydrogen-to-oxygen ratio always remains constant at 2:1.

Four important functions of lipids in the body:

- Energy source and reserve–Fat provides 80-90 percent of the energy requirement at rest. One gram of pure lipid contains about 9 calories of energy, more than twice the energy available from carbohydrate or protein.

- Protection of vital organs– The body’s internal fat (about 4 percent of the total) protects against trauma to vital organs like the heart, liver, kidneys, spleen, brain, and spinal cord.

- Thermal insulation–Fat keeps us warm!

- Vitamin carrier and hunger suppressor–Approximately 20g of daily dietary fat provides a sufficient source and transport medium for the four fat-soluble vitamins: A, D, E, and K. Severely reducing lipid intake depresses the body’s level of these vitamins and may lead to a deficiency.

| Classification | |||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

Simple lipids

Simple lipids (neutral fats) consist primarily of triglycerides and represent the major storage form of fat in human fat cells. Triglycerides contain two different clusters of atoms: one cluster, glycerol, and three clusters of unbranched carbon-chained atoms, called fatty acids, which bond to the glycerol. Fatty acids have as few as 4 carbon atoms or more than 20, although chain lengths of 16 and 18 carbons are most common.

Most naturally occurring fatty acids have a chain length categorized as short to very long. This becomes important since the different chain lengths undergo different metabolic fates. Short-chain and medium-chain fatty acids are quickly available for use as energy. Long-chain fatty acids, in contrast, undergo more complex processes and are deposited as fat in the liver and other body fat cells. Thus, the short- and medium-chain fatty acids often are considered “good” fats since they are easily metabolized and don’t necessarily contribute to fatty livers.

The four different types of fatty acids include:

- Short-chain fatty acids = <6 carbons. These are typically found in butter and some tropical fats.

- Medium-chain fatty acids = 6-12 carbons. You’ll find these in coconut oil, palm kernel oil, and breast milk.

- Long-chain fatty acids = 13-21 carbons. These are found in animal, fish, cocoa, seeds, nuts, and vegetable oils.

- Very-long-chain fatty acids = >22 carbons. Examples include omega-3 and omega-6 fatty acids found in fatty fish (omega-3) and some processed vegetable oils

Saturated, unsaturated, polyunsaturated, and trans fatty acids

A saturated fatty acid (SFA) contains only single bonds between carbon atoms; all remaining bonds attach to hydrogen. If carbon within a fatty acid chain binds the maximum possible number of hydrogen, the fatty acid molecule is said to be saturated with respect to hydrogen. Saturated fats occur primarily in animal products—beef, lamb, pork, chicken, egg yolk, and dairy fats of cream, milk, butter, and cheese. Plant SFAs include coconut oil, palm oil, and palm kernel oil (often called tropical oils) and vegetable shortening and hydrogenated margarine. Commercially prepared cakes, pies, and cookies contain plentiful amounts of saturated fatty acids

Unsaturated fatty acids (USFAs) contain one or more double bond. Since each double bond along the chain reduces the number of potential hydrogen-binding sites, the molecule is said to be unsaturated with respect to hydrogen. A monounsaturated fatty acid (MUSFA) contains just one double bond; examples include canola oil, olive oil, peanut oil, and the oil in almonds, pecans, and avocados. A polyunsaturated fatty acid (PUSFA) contains two or more double bonds. Safflower, sunflower, soybean, and corn oil fit this category. Several polyunsaturated fatty acids, most notably linoleic acid (an 18-carbon fatty acid with two double bonds present in cooking and salad oils), must originate from dietary sources because they serve as precursors of other fatty acids the body cannot synthesize. Thus they are termed essential fatty acids. The heart-healthy omega-3 fatty acids found in many fish also are polyunsaturated, long-chain fatty acids.

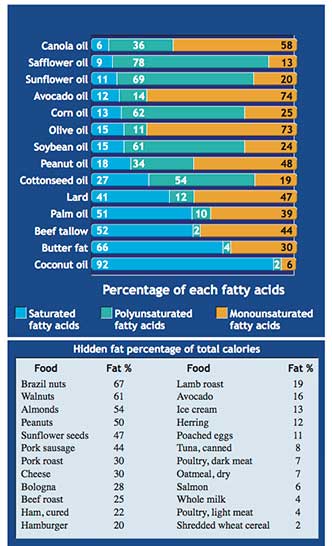

The figure here lists saturated, monounsaturated, and polyunsaturated fatty acid content in common fats and oils (expressed in grams per 100 grams of the lipid). The inset table shows the “hidden” total fat percentage in some popular foods without relative percentage of fatty acids.

The figure here lists saturated, monounsaturated, and polyunsaturated fatty acid content in common fats and oils (expressed in grams per 100 grams of the lipid). The inset table shows the “hidden” total fat percentage in some popular foods without relative percentage of fatty acids.

Several important points stand out in the figure:

First, most foods containing fat consist of a mixture of different proportions of saturated, monounsaturated, and polyunsaturated fats.

Second, there are differences in relative proportions of the types of fat found in vegetables and animals.

Most vegetable oils are high in polyunsaturated and monounsaturated fatty acids, whereas most animal fats are high in saturated and some monounsaturated fatty acids (except for palm, coconut, and olive oils). Olive oil is mostly monounsaturated (73 percent) with a small amount of polyunsaturated fat (11 percent). Lard is primarily equal parts saturated (47 percent) and monounsaturated (41 percent), but contains some polyunsaturated fatty acids as well (12 percent).

Meanwhile, a quick walk through the grocery story reveals countless food labels promising “zero trans fats.” Why should we care? Trans fatty acids derive from the partial hydrogenation of unsaturated corn, soybean, or sunflower oil. The hydrogenation process reduces or saturates unsaturated fat, generally to solifidy an oil at room temperature. The richest trans fat sources comprise vegetable shortenings, some margarines, crackers, candies, cookies, fried foods, baked goods, salad dressings, and other processed foods made with partially hydrogenated vegetable oils. Health concerns regarding trans fatty acids center on their detrimental effects on serum lipoproteins (see below) and overall heart health. They also play a possible role in cognitive decline with aging (Alzheimer’s disease and dementia).

Omega-3 and Omega-6 fatty acids

Omega-3 fatty acids are found both in plant- and animal-based foods. Plant-based omega-3s are shorter-chain fatty acids. These include alpha-linolenic acids (ALA) found in flaxseed oil (53 percent), canola oil (11 percent), English walnuts (9 percent), and soybean oil (7 percent). ALA is considered an essential fat because the body can’t make it. Thus you need to incorporate it into your diet. The most prevalent sources of omega-3s are eicosapentaenoic (EPA) and docosahexaenoic (DHA) acids found in cold, deep-water, fatty fish (cold-water herring, anchovies, sardines, salmon, mackerel, and sea mammals), shellfish, and krill. DHA is also found in smaller concentrations in the organs and fats of some land animals. Scientific studies confirm the importance of both DHA and EPA for optimal health.

Regular intake of fish (at least 2 servings or 8 oz. total per week) and possibly fish oil benefits overall heart disease risk and mortality rate. It protects against cognitive impairment (Alzheimer’s disease) and inflammatory disease, and lowers risk of colon polyps in women. It also offsets a smoker’s risk of contracting chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Omega-6 fatty acids include linoleic acid (LA), which is the most prevalent polyunsaturated fat in the typical Western diet. It can be found in processed oils–primarily corn oil–and also in sunflower, soybean, and canola oils. A longer-chain omega-6, arachidonic acid (AA), is found in liver, egg yolks, animal meats, and certain seafood.

Most Americans consume between 1.25 to 1.5 times more omega-6 than omega-3 fatty acids. The ideal ratio should be 1:1 or 0.75:1. While important in moderation, excess processed omega-6 fatty acids have been shown to contribute to chronic inflammation, which is most likely the source of just about every chronic disease seen today.

To get the omega-3 to omega-6 ratio closer to the ideal 1:1, cut back on excess vegetable oils. Consume fewer processed and baked foods. Common signs and symptoms of too much omega-6 fatty acids in the diet include flaky skin, alligator skin, frequent infections, dandruff, dry eyes, allergies, brittle or soft nails, poor wound healing, and cracked skin on heels or fingertips.

Lipoproteins: high-density, low-density, and very low-density

Lipoproteins are protein-fat carriers that categorize into types according to their size and density, and whether they transport cholesterol or triglyceride. Four types of lipoproteins exist on the basis of gravitational density.

Chylomicrons form when emulsified lipid droplets leave the intestine and enter lymphatic vessels. Normally, the liver metabolizes chylomicrons and sends them for storage in fat tissue. Chylomicrons also transport the fat-soluble vitamins A, D, E, and K.

High-density lipoproteins (HDLs) are produced in the liver and small intestine. HDLs contain the highest percentage of protein (~50 percent) and the least lipid (~20 percent) and cholesterol (~20 percent). HDL transports cholesterol away from the arteries to the liver for incorporation into bile and subsequent excretion, hence, HDL is referred to as the “good” cholesterol carrier.

Very low-density lipoproteins (VLDLs) are degraded in the liver to produce low-density lipoproteins. VLDLs contain the highest percentage of lipid (~95 percent), of which about 60 percent consists of triglycerides. VLDLs transport triglycerides to muscle and fat tissue.

Low-density lipoproteins (LDLs), commonly known as the “bad” cholesterol carrier, transport 60-80 percent of the total serum cholesterol to cells of the arterial wall. LDL ultimately contributes to unfavorable cellular changes that damage and narrow arteries that often result in heart disease.

Derived lipids

Cholesterol, the most widely known derived lipid, exists only in animal tissue. Cholesterol does not contain fatty acids but shares some of lipids’ physical and chemical characteristics, thus, cholesterol is considered a lipid. Cholesterol, widespread in the plasma membrane of all cells, originates either through the diet (exogenous cholesterol) or through cellular synthesis (endogenous cholesterol).

More endogenous cholesterol forms with a diet high in saturated fatty acids and trans fatty acids, which facilitate liver LDL cholesterol synthesis. Cholesterol participates in many bodily functions. It builds plasma membranes and serves as a precursor in synthesizing vitamin D, adrenal gland hormones, and the sex hormones estrogen, androgen, and progesterone. Cholesterol furnishes a key component for bile synthesis and plays a crucial role in forming tissues, organs, and body structures during fetal development.

Egg yolk provides a rich source of cholesterol (about 184-186 mg per egg), as do red meats and organ meats (liver, kidney, and brain). Shellfish (particularly shrimp), dairy products (ice cream, cream cheese, butter, and whole milk), fast-food breakfasts, and processed meats contain relatively large amounts of cholesterol.

Cholesterol and coronary heart disease risk

High levels of total serum cholesterol and cholesterol-rich LDL molecules are powerful predictors of increased risk for coronary artery disease. These become particularly potent when combined with such risk factors as cigarette smoking, physical inactivity, excess body fat, and untreated hypertension.

Current research suggests cholesterol excess in “susceptible” individuals eventually leads to atherosclerosis, a degenerative process that forms cholesterol-rich deposits (plaque) on the inner lining of medium and larger arteries, causing them to narrow and eventually close. Reducing saturated fatty acid and cholesterol intake generally lowers serum cholesterol, although for most people the effect remains modest and similar to the effects of body weight reduction. Also, increasing dietary intake of monounsaturated and polyunsaturated fatty acids lowers blood cholesterol, particularly LDL cholesterol.

Recommended lipid intake: What to eat?

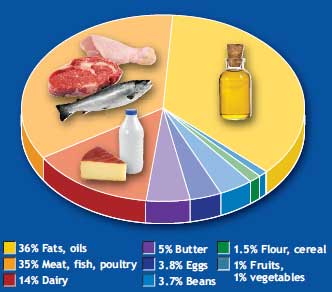

The figure on the right displays approximate percentage contribution of some common food groups to total lipid content of the typical American diet. The average American consumes about 58 percent of their total lipid intake from animal sources with more than 15 percent of the total calories as saturated fatty acids, the equivalent of more than 23 kg (51 lbs) yearly!

The figure on the right displays approximate percentage contribution of some common food groups to total lipid content of the typical American diet. The average American consumes about 58 percent of their total lipid intake from animal sources with more than 15 percent of the total calories as saturated fatty acids, the equivalent of more than 23 kg (51 lbs) yearly!

As noted in the beginning of this piece, ever since scientists began studying relationships between food consumption and development of chronic disease, systematic findings point to a causal link between disease risk and consumption of too much lipid.

Blood levels of trans fatty acids, saturated fatty acids (particularly long-chain fatty acids), cholesterol, and low-density lipoprotein are highly predictive of heart disease. Also, other types of fats (polyunsaturated fatty acids and omega-3 fatty acids) seem to be unrelated to disease, and in fact maybe protective. This research is not without detractors, however, who point to data showing saturated fatty acids are not as bad as suggested, and in fact may be desirable.

Nevertheless, based on the weight of evidence from animal experiments, as well as observational studies, clinical trials, and metabolic studies conducted in diverse human populations, most major science-based public health organizations throughout the world recommend an overall reduction of saturated and trans fatty acids from the human diet.

Current guidelines recommend a diet that contains ≤30-35 percent of total energy as fat, ≤10 percent of energy as saturated fatty acids, up to 10 percent of energy as polyunsaturated fatty acids, ≤300 mg of 1 cholesterol per day, and elimination of all trans fatty acids.

Debate and dispute

A recent study (Chowdhury 2014) challenged the accepted wisdom that saturated fat is inherently bad. The study evaluated 72 previously published studies on more than 600,000 people from 18 countries. Results indicated none of the types of saturated or polyunsaturated fatty acids had a significant impact on heart-disease risk. However, consumption of trans fat was tied to a 16 percent increase in disease risk. The author of the study concluded the following: “Current evidence does not clearly support cardiovascular guidelines that encourage high consumption of polyunsaturated fatty acids and low consumption of total saturated fats.”

The initial surge of global publicity for this study was electric. High-fat, low-carb advocates welcomed the news. But just as the ink dried on the publication, a revised version appeared, correcting several errors. The corrected version, of course, has not received much press. And although the study’s first author stands by the conclusions, a number of scientists have criticized the paper and called for its retraction.

“[The authors] have done a huge amount of damage,” said Walter Willett, chair of the nutrition department at the Harvard School of Public Health in a Science Insider article dated March 24, 2014. “I think a retraction with similar press promotion should be considered.”

Detractors of the research claim the authors omitted several important studies in their review or chose studies that were poorly conducted. Others cite the inherent limitation of the study design, and find fault with the interpretation of results. The press also played a role, wrongly interpreting the study results. In fact, one of the study authors recently stated: “We are not saying the guidelines are wrong and people can eat as much saturated fat as they want. We are saying that there is no strong support for the guidelines and we need more good trials.” This is a far different interpretation than presented by the press.

My recommendations

Until more research contradicts the wealth of data that support current recommendations to lower one’s intake of saturated fat, cholesterol, and processed foods, I believe the following suggestions seem prudent:

- Replace at least a portion of saturated fatty acids and all trans fatty acids with nonhydrogenated, monounsaturated oil (olive and safflower) and polyunsaturated oil (soybean, corn, and sunflower).

- Replace or reduce cheese and red meat (particularly processed meat) with fresh poultry and fish.

- Limit total lipid intake to 10-30 percent of total calorie intake; consider consuming no more than 10 percent of total daily caloric intake as saturated fatty acids (regardless of source). That’s about 300 calories or 30-35 grams for the average person who consumes 3,000 calories per day.

- Consider consuming more whole-food, plant-based options as an alternative source of lipid.

- Increase regular physical activity: Move more, sit less.

References:

- Chowdhury, R., et al. Association of Dietary, Circulating, and Supplement Fatty Acids With Coronary Risk: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Ann Int Med. 2014; 160(6): 398-406.

- Darroll, M.D., et al. Total and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol in adults: National health and nutrition examination survey, 2011-2012. NCHS Data Brief. No. 132, Oct 2013. Source: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db132.pdf.

- Diet, Nutrition, and the Prevention of Chronic Diseases. WHO Technical Report Series 916. Report of a Joint WHO/FAO Expert Consultation. 2003. Source: http://whqlibdoc.who.int/trs/who_trs_916.pdf

- http://news.sciencemag.org/health/2014/03/scientists-fix-errors-controversial-paper-about-saturated-fats

- http://www.plantpositive.com/

- http://www.plantpositive.com/siri-tarinos-meta-analysis-par/

- Kris-Etherton P., et al. Summary of the scientific conference on dietary fatty acids and cardiovascular health: conference summary from the nutrition committee of the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2001 Feb 20;103(7):1034-9.

- Jakobsen, M.U., et al. Major types of dietary fat and risk of coronary heart disease: a pooled analysis of 11 cohort studies. Am J Clin Nutr 2009:1425-32.

- Koh, A.S., et al. The association between dietary omega-3 fatty acids and cardiovascular death: the Singapore Chinese Health Study. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2013 Dec 16. [Epub ahead of print]

- Siri-Tarino, P.W., et. al. Meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies evaluating the association of saturated fat with cardiovascular dis- ease. Am J Clin Nutr. 2010;91:535-46.

- Stamler, J., et al. Is the relationship between serum cholesterol and risk of premature death from coronary heart disease continuous or graded? Findings in 356,222 primary screenees of the Multiple Risk Factor Intervention Trial (MRFIT). JAMA 256(20):2823–8. 1986.

- Wallstrom, P., et al. Dietary fiber and saturated fat intake associations with cardiovascular disease differ by sex in the Malmo Diet and Cancer Cohort: a prospective study. PLoS One. 2012;7:e31637.

Chris Little

On the subject of food labeling (trans fats), let’s not forget that current US labeling laws permit producers to put “0” on the label if the content is less than 1 gram.

So those “0” trans fat products you’re eating may give you several grams of trans fat if you eat more than one serving.

Reply

John Roach - 1965 and 1993

Thank you for not taking a position, then defending it. It is refreshing to hear facts then opinions from the various studies.

It is worth noting that the epidemic of obesity and diabetes is timed to eating guidelines that told us to reduce protein and increase carbohydrate intake for heart health. Yet obesity and diabetes are considered risks to heart health.

Reply

VCO Supplier - 2016

This Article very usefull for many people.

Health experts have long recommended that you avoid Coconut oil because of its high saturated fat content. The molecular structure of the saturated fat in coconut oil differs from the kind found in animal products, though, making it a potential dietary boon rather than bust. When included as part of a low-calorie, portion-controlled diet and exercise routine, Coconut oil may help your body burn fat rather than store it.

Reply