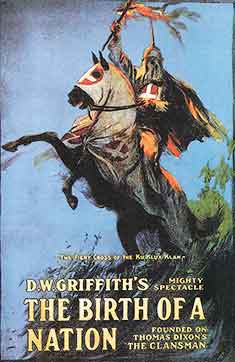

Editor’s Note: This column is the first in a two-part series detailing the making of D.W. Griffith’s controversial film The Birth of a Nation. Griffith set a new standard for cinematic achievement with his epic production. But the film’s portrayal of African Americans in post-Civil War society as ignorant, predatory, and unsuited to citizenship helped set in motion a series of devastating social and political setbacks, the effects of which can still be felt today. Read Part II.

Part 1 – The making of the film: 1914

Monumental American film history was being made at this very moment 100 years ago. In July 1914, D.W. Griffith began shooting the Civil War/Reconstruction epic that would become The Birth of a Nation, a work of remarkable storytelling, cinematic art, and politically provocative content.

Monumental American film history was being made at this very moment 100 years ago. In July 1914, D.W. Griffith began shooting the Civil War/Reconstruction epic that would become The Birth of a Nation, a work of remarkable storytelling, cinematic art, and politically provocative content.

Filming took place in and around Los Angeles (with some Southern plantation scenes shot in Mexico) and was completed in October. Griffith spent four months in post-production and in preparation of a rousing musical score for the film’s release on Feb. 8, 1915.

The director shot tens of thousands of feet of film, and his final edit came in at 13,000-feet. With a running time of three-hours and 50-minutes, Griffith set a new standard in the fledgling motion picture medium. Star Lillian Gish says in her memoir, The Movies, Mr. Griffith and Me, that the epic cost about $91,000: $61,000 to shoot and $30,000 to distribute and promote.

Back story

When Griffith’s film opened in Los Angeles at Clune’s Auditorium, it was titled The Clansman, a direct reference to the historical epic’s conceptual origins. Thomas Dixon Jr. (1864-1946), a North Carolina-born minister and novelist, had grown up listening to family tales about the Civil War and Southern Reconstruction. Dixon’s father and his uncle, Colonel Leroy McAfee, had been members of the western North Carolina Ku Klux Klan. In 1883 Dixon graduated from Wake Forest University and then entered Johns Hopkins University as a scholarship student for graduate study in history. Fellow classmate and future U.S. President Woodrow Wilson became a close friend.

Following work as an ordained minister, lawyer, popular public orator, and North Carolina legislator, Dixon at the beginning of the 20th century jumped into the by-then lucrative field of writing pro-Southern Reconstruction novels. In the 1880s chivalrous romantic fiction had flourished, with many works centered on the Civil War’s immediate and uncertain aftermath — inspired in part by the huge popularity of the 1879 novel A Fool’s Errand, By One of the Fools, authored by Albion W. Tourgee.

Tourgee was an Ohioan and pioneer civil rights activist who lived briefly in the South after the war. The novel’s largely autobiographical plot tells the story of Comfort Servosse (fictionally a Michigander) who moves to North Carolina to offer his legal services during the early years of Reconstruction. Met with personal, social, and political animosity, Servosse (self-described as one of “the fools”) returns home to the North.

Tourgee’s novel openly denounced Southern attitudes of intolerance and viewed the Ku Klux Klan as the tyrannical outgrowth of this intolerance. A Fool’s Errand received wide critical praise and sold nearly 90,000 copies in the year after its publication. Some critics described the book as “the new Uncle Tom’s Cabin.”

A battle of the books

In 1884 author N. J. Floyd published Thorns in the Flesh, a pro-Klan novel which, on the title page, declared itself “an answer to A Fool’s Errand and other such slanders.” Pro-South fiction of similar ilk followed: Ku Klux Klan No. 40 (1895) by Thomas Jefferson Jerome; The Red Rock (1898) by Nelson Thomas Page; and Gabriel Tolliver: A Story of Reconstruction (1902) by Joel Chandler Harris. In these novels the South was depicted as a place of idyllic beauty whose people had been regrettably deprived by the Civil War and Reconstruction of a peaceful and innocent way of life. The antagonists often were Freedmen’s Bureau agents, carpetbagger leaders, and what the authors viewed as “manipulated” ex-slaves. The KKK or other mob groups acted to restore “order and dignity” to the South.

Inspired by childhood memories, Thomas Dixon Jr’s intentions fell in line with earlier pro-Klan/Reconstruction novels. His first book, The Leopard’s Spots, was published in 1902 and dealt with late-19th-century racial relations in the South. Its theme was the ideological claim of white superiority and the enduring inferiority of blacks; hence, the book’s symbolic title taken from the biblical passage: “Can the Ethiopian change his skin, or the leopard his spots?”(Jeremiah 13:23). In its first year Dixon’s novel sold about 100,000 copies, stimulated in part by a thesis that generated enormous controversy.

Inspired by childhood memories, Thomas Dixon Jr’s intentions fell in line with earlier pro-Klan/Reconstruction novels. His first book, The Leopard’s Spots, was published in 1902 and dealt with late-19th-century racial relations in the South. Its theme was the ideological claim of white superiority and the enduring inferiority of blacks; hence, the book’s symbolic title taken from the biblical passage: “Can the Ethiopian change his skin, or the leopard his spots?”(Jeremiah 13:23). In its first year Dixon’s novel sold about 100,000 copies, stimulated in part by a thesis that generated enormous controversy.

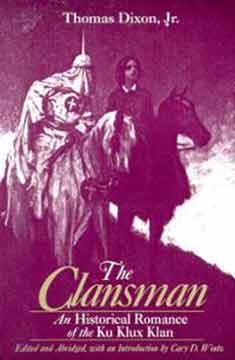

In 1903 an inspired Dixon began work on a sequel (a prequel chronologically) that would examine in greater detail a history of events beginning with the last month of Abraham Lincoln’s presidency and concluding with the successful emergence of the Ku Klux Klan in the late 1860s. The novel, published in 1905, was titled The Clansman: An Historical Romance of the Ku Klux Klan. In its introduction Dixon maintained that the novel developed “the true story of the ‘Ku Klux Klan Conspiracy,’ which overturned the Reconstruction regime.”

Its villain was Republican leader Austin Stoneman (a fictionalized Congressman Thaddeus Stevens) who, the novel says, “made a bold attempt … to Africanize 10 great states of the Union.” In depicting Stoneman as the source of the South’s woes during Reconstruction, plot details set in Piedmont, S.C., include an elected mulatto lieutenant governor and a black militia, both representatives of Austin Stoneman; disenfranchisement of white voters; a black-dominated and vindictive South Carolina legislature in 1868; and sensationally, the rape by a black militia captain of a young white woman who commits suicide soon after.

The accumulation of these and other damning acts that befall the people of Piedmont was meant to justify a full purge by the Ku Klux Klan of Austin Stoneman’s northern legions. The Clansman ranked among the top-five best-selling novels published in 1905 and despite criticism that it was “disgusting” and “obnoxious” was made into a popular stage play the same year. When criticized for his sensational interpretation of history and his attack on Thaddeus Stevens, Dixon defied anyone to find “a single word, line, sentence, paragraph, page, or chapter in The Clansman in which I have done Thad Stevens an injustice.”

It would take years to sort out the accuracy, or lack thereof, of this bold claim.

Enter D. W. Griffith

Image: IMDB

In 1913 Frank Woods, a Hollywood scenario writer, came to D.W.Griffith with the idea of filming The Clansman. Griffith was by then the pre-eminent film director in the U.S. — in the world, he believed — and had been on the lookout for an appropriate topic for film treatment that would show off his cinematic artistry to fullest advantage.

Griffith (himself a Southerner from Kentucky) wrote later, “When Mr. Woods suggested The Clansman to me as a subject it hit me hard. I hoped at once it could be done, for the South had been absorbed into the very fiber of my being.” Lillian Gish quotes Griffith as saying, “I’m going to tell the truth about the War Between the States. It hasn’t been told accurately in history books. Only the winning side gets to tell its story.”

In April 1914 the Mutual (Film) Company, for whom Griffith was a director, agreed to finance a screen version of The Clansman. Dixon sold the rights of his two novels, as well as the stage adaptation, to Mutual for a 25 percent interest in the motion picture’s profits. Three months later, with a screenplay by Frank Woods, Griffith began filming The Clansman.

Expansion and authenticity: The first half

In addition to the postwar storyline of Dixon’s novels, Griffith decided to expand the film to include a treatment of the Civil War itself. This move would become a major factor in the film’s stunning critical reception and the persuasive power of Dixon’s ideological take on Reconstruction history.

In preparation for the shooting of the film’s prewar and war periods Griffith scoured factual sources: Harper’s Pictorial History of the Civil War, published volumes of Mathew Brady’s Civil War photographs, paintings and photographs of the famous historical figures who would be characters in the film, and biographies of Abraham Lincoln. Using these research materials, Griffith’s crew secured California shooting locations that resembled actual Civil War battle sites.

Cast members bore striking resemblances to Robert E. Lee, Ulysses S. Grant, Senator Charles Sumner, and Abraham Lincoln. This made for effective recreations of familiar war-era photographs: Lincoln’s first call for volunteers, the signing of the Emancipation Proclamation, the surrender at Appomattox, and others. Griffith posed the actors in static positions, then brought the photograph facsimiles to life so that audiences could “see” history in the making. The director followed precisely the chronological account of the president’s assassination as told in Lincoln: A History by Nicolay and Hay in re-staging the events in Ford’s Theater on April 14, 1865. He set the assassination scenes inside an exact replica of the theater, with attention to both size and architectural detail.Cinematographer Billy Bitzer’s camera work for the war scenes was altogether impressive: in its visual scope (realistic long shots filled with action, cannon fire, and smoke) and in its intensely personal close shots of young Southern and Northern soldiers falling injured and dying in the battles. After the final battle of the war at Petersburg, static shots fill the screen of heaps of dead bodies, a reflective moment for the Civil War’s tragic toll, and what a title in the completed film would refer to ironically as “War’s Peace.”

The spectacularly realistic and moving first half of Griffith’s film concluded with Lincoln’s assassination. Characters in South Carolina are filmed reacting to a news headline about the assassination and realizing they have lost a “friend.”

Political drama: The second half

What happened in D.W.Griffith’s brilliant filming strategies and his artistic skills in the film’s first half served as a forceful preface to the merger of fact and fiction that would follow in the second half’s stirring treatment of Thomas Dixon’s interpretation of Reconstruction as detailed in his novel The Clansman.

What happened in D.W.Griffith’s brilliant filming strategies and his artistic skills in the film’s first half served as a forceful preface to the merger of fact and fiction that would follow in the second half’s stirring treatment of Thomas Dixon’s interpretation of Reconstruction as detailed in his novel The Clansman.

Working in a silent-film era and without Dixon’s inflammatory rhetoric, Griffith faced the task of developing emotionally charged screen renderings of characters and incidents that framed Dixon’s novel: radical Republican Austin Stoneman (Thaddeus Stevens) and his handpicked cohorts; a belittling black militia shown forcing whites off the street and demanding salutes; Freedmen’s Bureau and Northern scalawags calling ex-slaves away from their work in the fields with offers of 40 acres and a mule; a predominantly black legislature drinking whiskey in South Carolina’s House chambers and passing laws permitting interracial marriage as white women look on from the gallery above; a womanizing black supremacist lieutenant governor who, near the film’s end, attempts to force the female protagonist (portrayed by Lillian Gish) to marry him; and the stalking of a young Southern woman by a militia captain.

Griffith left out the rape sequence in Dixon’s novel but the young woman, fearing her pursuer, jumps from a cliff to her death. Thus Griffith had built an emotionally provocative case for the rise of the Ku Klux Klan on film. His grand finale, a tour de force upsurge of determined action, showed the various Klan bands from North and South Carolina assembling on horseback for a “heroic ride” to relieve the people of Piedmont of their Northern-imposed agony. Billy Bitzer’s innovative camera tracked ahead of the charging Klansmen. Holes dug in the ground created the illusion of flying hooves. And since horses were scarce at the time, due to the onset of World War I, Griffith relied on other creative filming and editing tricks to give the sense of a massive Klan uprising.

In essence D.W. Griffith created the first great motion picture docudrama, a work that would move audiences to standing ovations. Because of the Civil War treatment and its chivalrous conclusion, Thomas Dixon insisted that the film’s title be changed to The Birth of a Nation. Proudly he took the film to the White House for a screening by his friend Woodrow Wilson, who is said to have declared afterward: “It’s like writing history with lightning.”

Negative reactions to the film were immediate and vociferous — from picketers who reacted to the stereotyped treatment of blacks and the film’s incendiary tone, which some observers described as having “worked the audience into a frenzy.” Newspaper editorials challenged Griffith’s interpretation of Reconstruction history and his characterization of political leaders of that period. The charges against The Birth of a Nation surprised Griffith, and he took to the street to hand out pamphlets that defended the film’s views of post-Civil War history.

The film’s impact on society was both immediate and long-lasting. In 1915 the Ku Klux Klan, which had been driven out of business by the Federal Force Acts in the 1870s, would be re-chartered in Georgia on the occasion of the film’s release there. Throughout much of the 20th century the movie resurfaced from time to time as a propaganda vehicle for disgruntled political factions.

Coming attractions

The Birth of a Nation’s afterlife forms the second part of this story in the February 2015 issue of Michigan Today, at the time of the film’s centenary anniversary. That piece is titled “A film that won’t go away.”

David Rigan - 1970, 1973

I have heard that Ward Bond played Ulysses S. Grant in Birth of a Nation. I am wondering if this is accurate.

Reply

Deborah Holdship

From Frank Beaver: “British actor Donald Crisp portrayed U.S. Grant. Crisp won a Best Supporting Actor Oscar for his performance in John Ford’s HOW GREEN WAS MY VALLEY (1941).”

Reply

Margaret Bennett - 1958, 1975

How do I access the film “Birth of a Nation”? And, a book, if such a book exists.

Thanks,

–Margaret Bennett

Reply

Deborah Holdship

Frank Beaver reports: “A version of THE BIRTH OF A NATION is available from Amazon.com, ‘tho some libraries have copies of the film as well as Thomas Dixon’s THE CLANSMAN — which is the narrative source of the film’s inflammatory second half.” Best, F.

Reply

adrian ciugudean - 1991

I appreciate the scholarly treatment—even-handed portrayal–of this monumental production in the history of cinematography. Of course, I would expect nothing less from a professor at Michigan.

Reply

Harry Epstein (aka Harry Peerce in SAG, AFTRA and Equity) - 1971, 1972

thanks for sending this terrific piece Dr. Beaver !

Reply

Martha S. Jones

Professor Frank Beaver’s article on D.W. Griffith’s The Birth of a Nation provides an important opportunity to explore the film’s impact upon culture and politics in the United States. When we teach the history of Reconstruction, The Birth of a Nation is often required viewing, precisely because it is one of the cultural products that helped engender the deep misunderstandings of Reconstruction that characterized the first half of the 20th century, and that linger into our own time. Through intensive research in the archival materials of the post-Civil War period, historians have demonstrated that the Reconstruction era was a visionary moment, characterized by an ambitious experiment in the enforcement of equal rights, not a vindictive Northern attack on white people in the South, as Griffith portrayed it. During Reconstruction, Congress attempted to set in place an inter-racial democracy, one in which all Americans, including former slaves, were to be empowered in law and politics.

Though short-lived, Reconstruction remains relevant today. In law, it generated the Thirteenth, Fourteenth, and Fifteenth Amendments to the U.S. Constitution, the development of African American political and cultural institutions, an example of cross-racial political alliances, and the establishment of public education in the American South. The achievements of the Reconstruction, and the subsequent judicial and political retreat from its egalitarian goals, continue to inform today’s discussions of race, law, and politics.

Reconstruction’s end marked the beginning of a new and bitter era in American racial politics. It is this period of widespread and explicit advocacy of what its proponents did not hesitate to call “white supremacy” that frames Griffith’s film. Drawing upon literature and myth, the filmmaker offered up a false and misleading portrayal of the nation’s history. He valorized the Ku Klux Klan, thus endorsing what is widely recognized as having been a domestic terrorist organization. He caricatured African Americans as unworthy of political or civil rights, ignoring the responsibilities they had borne as soldiers, and parodying their access to office-holding and citizenship in the late 1860s and early 1870s. Griffith turned his back on history and produced propaganda. He set aside what many Americans had known as a period of striving for democratic ideals, and substituted a fantasy that imagined the nation as having been wounded by Reconstruction, and then healed by the reconciliation of white Americans across the North-South divide.

To construct this portrait, the film alternately ignored and mocked the contributions of, and the political and social demands made by, African Americans. Griffith’s cultural handiwork did not stand alone. It was part of a broader campaign that was enacted in the highest echelons of law and politics. The U.S. Supreme Court approved state-mandated racial segregation in the 1896 case of Plessy v. Ferguson, and the denial of voting rights to black citizens in Giles v. Harris in 1903. President Woodrow Wilson, who endorsed The Birth of a Nation, oversaw the segregation of the federal government. Ultimately, President Wilson and members of the Court and Congress would be among the first to view Griffith’s film. What they saw was a story in which the contributions of black Americans were extinguished from the nation’s public memory, and replaced by a nation stitched back together — North and South — under white supremacy.

The accomplishments of Reconstruction were thus destroyed by a campaign of forced segregation, disfranchisement, and racial violence. In this, Griffith’s film played a critical role. Today, The Birth of a Nation provides students with an example of how the era of Jim Crow came to be set in place. Historians played no small role in this story. In our classrooms students can also see the ways in which they contributed to this imagined “reconciliation” of the nation. Columbia University’s William Dunning and his students, for example, are remembered for having published histories whose central narrative complemented the view put forward in Griffith’s film. They too ignored evidence of Reconstruction’s democratic ideals and deemed the period a tragic mistake.

Griffith’s film was an instrument of cultural repression that was epic in scope, one that helped to provide justification for the racial oppression that would remain in place until the victories of the modern civil rights movement. As Professor Beaver’s second installment promises to chronicle, opposition to the movie was swift and strong. Only by first understanding the role that The Birth of a Nation played in imposing a Jim Crow social and political order can we make sense of the strong reaction to the film. The protests, civil unrest, and lynching that followed its public debut were testament to its troubled point of view and political climate.

No student at the University of Michigan should miss the opportunity to understand Griffith’s cinematic achievement. Still, no study of the film would be complete without also explaining its toxic influence on the longer story of race and rights in the United States.

Martha S. Jones

Arthur F. Thurnau Professor

Associate Professor of History and Afroamerican and African Studies

Visiting Professor of Law

Co-Director, Michigan Law Program in Race, Law & History

Reply