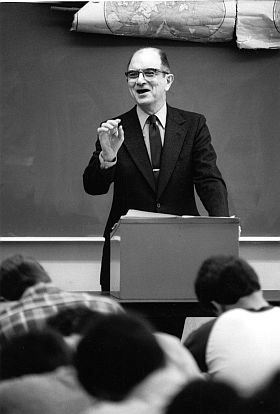

History professor Sidney Fine, who died in March 2009, loved life, learning and his students. (Photo courtesy U-M Bentley Historical Library.)

The U-M historian Sidney Fine died in Ann Arbor on the last day of March at the age of 88. To a great many alumni, that news will surely trigger a jolt of sadness and memory. Each department has had its great figures, of course, its important scholars and popular teachers. But few can claim a figure like Fine, who combined the roles of teacher, scholar and mentor so memorably, and who exerted an influence for good in so many lives.

Fine was a native of Cleveland who became a Michigan man through and through. A Navy veteran of World War II, he earned his Ph.D. at U-M in 1948, then taught in Ann Arbor for the next 53 years, apparently the longest span of any U-M faculty member ever. He loved the University in all its dimensions (though never with uncritical eyes), from the Bentley Historical Library on North Campus, where he was an indefatigable researcher and adviser, to Michigan Stadium, where he seldom if ever missed a home game.

Bo Schembechler himself presented Fine with an autographed football at his retirement party in 1991—an occasion that turned out to be premature, since the Michigan legislature did away with its mandatory retirement rule for college professors principally to allow Fine to keep teaching beyond the age of 70. He did so for 10 more years. By the time he left the classroom in 2001, he had taught between 25,000 and 30,000 students, and there is no doubt that he was one of the most popular teachers in the University’s history.

He was also an influential and prolific writer. He began his career as a student of intellectual history—his “Laissez Faire and the General-Welfare State: A Study of Conflict in American Thought, 1865-1901” remains a classic of that field—then turned to labor history, where he made his largest mark as a scholar. Many of his books told the story of 20th-century U.S. history as seen through the prism of urban, industrial society in Michigan—its labor strife in the 1930s, its racial turmoil in the 1960s, its public policy in the 1950s and ’60s. He wrote a three-volume biography of one of Michigan’s most important public servants, the Detroit mayor, governor and U.S. Supreme Court Justice Frank Murphy.

He did all this with enviable pleasure. “I live with the best wife [Jean Fine] in the best house in the best town in the world,” he would say. “And I have the best job in the best university.” He would travel anywhere in pursuit of his research, yet he could not endure a vacation of more than a week, saying, “I have to get back to my work.”

In the auditoriums where he taught standing-room-only courses about the United States in the 20th century, Fine was master of a teaching method that in other instructors was considered dull and outmoded—the lecture. He scorned the showmanship that makes some teachers popular. Instead, he earned students’ attention and respect through a magnetic combination of personality, intelligence and enthusiasm for the story he was telling day by day. He had a superb sense of humor and occasionally told a funny story in class, but only in the service of a point he wished to make.

Certainly his students completed his courses in possession of a larger body of knowledge than they had when they began. But I suspect the more lasting gift he gave them was his contagious faith simply that the past matters. I heard him say once that he considered an important part of his job to be inculcating a respect for the discipline of history. I’m sure he did so with most of his students.

“He was intensely passionate about the subject matter,” said MaryAnn Sarosi, a student of Fine’s in the 1980s and now assistant dean of public service in the Law School. “People felt it. It was palpable.

“You didn’t want to disappoint him,” she said. “How does someone instill that in a room of 150 students? And I’m sure I wasn’t the only one who felt that way.”

Every week, students lined the third floor of Haven Hall to seek his advice and help. They found him both friendly and demanding. He never behaved as the students’ pal, but he did establish a sympathetic connection with them. He made it obvious that he cared about what they learned and how their lives were going.

In these talks students saw what happens when keen native intelligence is seasoned with decades of study and analysis. Conversation with him could be something of a spectator sport, since his ebullience was often unstoppable. Yet it was also a delight to experience. His memory appeared to be limitless. He could reach into brain storage for an anecdote from his boyhood in Depression-era Cleveland, an obscure fact about Woodrow Wilson’s role in the peace negotiations after World War I, an ancient baseball statistic, a detail about a student’s family.

In the seminar rooms where he taught graduate students, he set an example that has radiated through many academic careers to touch students who never have heard his name.

“He was a perfect mentor,” said David M. Katzman, a highly regarded historian at the University of Kansas. “We disagreed about a lot of things—I was a campus activist and involved in the antiwar movement in the 1960s—but Sidney supported my work and me personally. Indeed, he stretched himself to allow me to follow my own path. At every turn, he encouraged me, critiqued my work, and challenged me intellectually. He gave me freedom to shape my own graduate work as long as I met Michigan’s standards and his own higher standards.

“He set a model for generosity and rigor. I have received some awards for mentoring graduate students, and each one is an affirmation of Sidney. I have just passed on to my students what Sidney did for me. And when my students ask me how they can repay me, I answer as Sidney did: ‘You repay me by doing the same for your students.’ The cycle that Sidney started goes on.”