http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9gw5d-j6eVM

When University of Michigan glassblower Harald Eberhart hears President Barack Obama call for more research on fuel cells, batteries, solar and wind power, it fills him with hope—and with dread. Energy research—just about any research, really—means business will be picking up for the men and women who craft molten glass into the one-of-a-kind widgets and whatzits of science.

More work, but for fewer and fewer glassblowers.

Eberhart and fellow U-M glassblower Roy Wentz produce custom scientific glassware for U-M’s School of Engineering and chemistry department, respectively. That could mean anything from a flameless catalytic heater made to produce heat in Antarctica to a Schlenk line—an intricate piece of equipment that lets chemists run experiments with oxygen-sensitive chemicals.

Even in this age of ever-improving technology and materials, some things simply require glass.

Scientists like that it’s transparent and doesn’t contaminate their samples. In the hands of a master glassblower it can take almost any form—lenses, containers, valves, connectors, thick slabs and thin films.

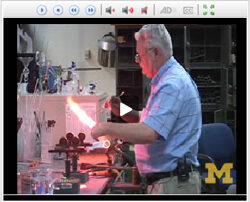

U-M scientific glassblower Harald Eberhart heats a tube of quartz to 2,000 degrees C. Eberhart, who has been blowing glass since age 14, can make complex, one-of-a-kind scientific instruments to order, saving the university time and money and creating new research possibilities for its scientists. (Photo: Martin Vloet, U-M Photo Services.)

“Say you wanted something spherical, but with essentially no weight,” said chemistry professor Rick Francis, who’s also associate dean for budget in the college of LSA. “You’d go on the web, and you could advertise, but I don’t think you’d find anything you could purchase. You need not just a glassblower, but one that knows the tricks of the trade, who knows how thin you can blow the glass. Some of this stuff is Byzantine in its complexity.”

Glass made from quartz can go from a 2,000-degree-Celsius propane/oxygen flame to a beaker of cold water without breaking. Because it can withstand those extremes quartz researchers use quartz containers to change materials from solid to liquid to gas. All computer chips are made in quartz tubes because quartz is the only material that can handle the heat without contaminating its contents.

Under compression, glass is stronger than steel.

“People think glass is fragile,” Eberhart said. “But I can make glass so hard you can pound a nail into a piece of wood with it.”

Roy Wentz uses a tube to blow air into an instrument he is repairing for the chemistry department. Wentz, 67, spent 10 years training his son the glassblowing trade, but many institutions have cut their in-house glassblowers, and the traditional knowledge is fading. (Photo: Martin Vloet, U-M Photo Services.)

And yes, glass does break, but it’s fairly easily repaired.

Francis says he once took Wentz a large bell jar that he thought was a lost cause and “watched him perform a feat of pure magic.”

The jar was about 30 inches tall, 18 inches in diameter and chipped all the way around the bottom, the surface that must be smooth to create a vacuum seal. Wentz made a little scratch about half an inch up, set the jar on a turntable, heated the scratch with a torch and sent the crack all the way around the jar. A perfect ring of damaged glass snapped off, leaving a clean new edge that could be ground and tempered to seal again, giving new life to a $2,200 piece of equipment.

And that’s just the part that’s easy to quantify.

“The value is in what the glass can do,” Eberhart said. “If it works, papers are written, grants are allocated, graduate students are hired, patents are awarded and professors gain fame.”

“This isn’t something we can get done easily outside the institution,” Francis said. “You can easily imagine an experiment that you could not do without the glassblower. That’s why they still have a job.”

But Eberhart, 59, and Wentz, 67, are among just 69 university glassblowers left in the United States, according to a 2005 survey of the American Scientific Glassblowers Society. Within the next seven years, Eberhart says, half of those will retire, and in many cases they won’t be replaced.

Universities around the country are closing their glass shops, opting to contract that work out rather than pay a full-time salary. And there’s very little system for developing the next generation of scientific glassblowers.

Their dwindling numbers will quietly change the face, and the pace, of scientific research. “I blow glass and they can have it in three days,” said Eberhart, who works for U-M’s engineering department. “If I didn’t exist they’d have to find a glassblower 500 miles away, they’d have to use UPS Ground (to have the glassware shipped) and if there’s a miscommunication they may end up purchasing something they can’t use.”

Fathers and sons

Wentz and Eberhart are products of an age when master glassblowers from Holland, Hungary and Austria immigrated to the U.S. in great numbers. Both learned their trade the old-fashioned way and have been at it more than 40 years. Wentz first apprenticed under his uncle; Eberhart started learning at his father’s side when he was 14. Both, in turn, taught their sons.

But that may be where the legacy ends.

When Eberhart’s father was growing up in Austria, it took eight years to become a master glassblower. These days, he says, it takes six years to be certified in Europe. The only school in the U.S. that trains glassblowers—Salem Community College in Carneys Point, N.J.—has a two-year course in scientific glass technology. But there’s no substitute for experience, especially when it comes to the intricate glassware used in research.

“It’s one of the few things that’s still done by hand,” Eberhart said. “I do have a lathe, but that’s only used when something’s too big or too hot to hold. It’s all hand-eye. It’s like playing the fiddle. The more you play, the better you become.”

Eberhart’s son, Matias, went through the Carneys Point program, but there were no jobs when he graduated, his father said. Matias went into a computer field instead.

University glassblowers generally earn more than their industrial counterparts—the average university salary in the Midwest is about $60,000 and both of U-M’s glassblower make closer to $70,000. But it’s still not much of a growth profession.

Wentz spent 10 years training his son, Christopher, to take his place in the chemistry department glass shop. Christopher worked with his dad from the time he was in high school, eventually landing a part-time and then full-time position at Michigan. But the university was paying him about half the market rate, and when the economy tightened he couldn’t find enough outside work to make ends meet. He quit in February 2008 to get a job in construction.

Francis says there may not have been enough work to justify two full-time glassblowers. Christopher has since found work with a cousin, blowing glass in a commercial shop—the kind of place U-M researchers would turn to if the university had no glass shop.

Love what you do

So given the job scarcity and the long road to mastery, why do people still blow glass for a living? “It’s addictive,” Eberhart said. “You will never meet a glassblower who doesn’t love his work. It changes constantly, and the medium of glass is the most versatile on the planet.”

Both men enjoy the challenge of designing and making things that have never been made before—sometimes from little more than a researcher’s description of what it’s supposed to do.

“The physicists are the nutcases,” Wentz said. “They’re always on the fringe of trying to figure things out. Some of the things I’ve done done for the physics department are very challenging. They always want the impossible.”

They know their work supports important research in a unique and critical way, whether its a complex reaction chamber or a the piece of scrap bent at just the right angle to make a graduate student’s project work. And that feels good.

“I enjoy being around the graduate students,” Wentz said. “If you’re around old fogies, all you do is focus on old fogy stuff.”

Wentz has a map of the world in his shop, and when students come in he has them point out their home. He soaks up geography, culture, religion, perspective. Working with students is how he travels the world, he says.

“There’s a student from Iran, I call him ‘my favorite Persian’. He comes by and I say, ‘What’s the news from Iran?’ Rather than get it from the biased news media, he gets it right from home because he just he called his mom.”

Wentz will be 68 this spring. There was a time when he thought he’d retire at 70, though given the state of his retirement savings, that doesn’t seem so likely anymore.

“I’m going to keep working until the Lord shows me it’s time to quit,” he said. “I love it. As long as my health is good and I enjoy this, it would be stupid to retire.”

Lauren K - 2012

Ray Wentz is one of the nicest people I’ve ever met. I’m really happy to have read this article. These two glassblowers are very talented and modest workers that deserve this kind of recognition.

Reply