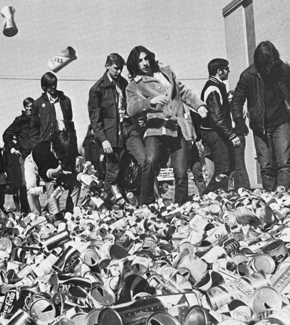

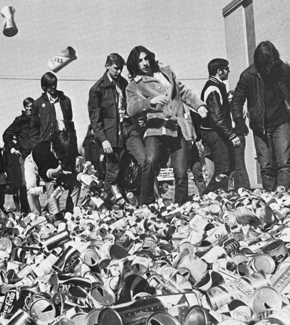

In the days before recycling became common — partly as a result of the 1970s boom in environmental awareness — participants in U-M’s Teach-In on the Environment dumped piles of empty cans at a local bottling plant. (Reportedly, the students later picked up the cans and threw them away.) (Photo: Michiganensian. Courtesy Bentley Historical Library.)

In the fall of 1969, after long hours in the lab, U-M grad students in zoology and botany often wound up at the big round tables at Metzger’s on Washington Street. Over pitchers of beer, discussion often turned to the waterbirds killed in that year’s oil spill off Santa Barbara, California; to the Cuyahoga River in Cleveland, so clogged with oil that the river itself had caught fire; and to the mats of algae so dense on the surface of Lake Erie that rats could be seen scuttling across the lake. Then one night the topic shifted from pollution to what should be done about it. The “zo” and botany students learned that friends in the School of Natural Resources were thinking the same way, and the casual bull sessions turned into serious meetings.

Some of them had been in Ann Arbor in 1965, when U-M students held the first teach-in on the war in Vietnam. The same approach could work now, they thought, but it should be even bigger. “It was decided early that if we were going to do something, it had to be different from most university activism events, which just involved university personnel,” recalled John Russell, who had just left the botany program to teach biology and conservation at Ann Arbor Pioneer High School. “And it had to include all aspects of the community, all political parties, all ethnic groups. So it was to be a very comprehensive thing. It was the end of the ’60s. There was nothing wrong with dreaming big.”

A button from the 1970 Teach-In on the Environment. (Photo courtesy John Russell.)

They started a group called Environmental Action for Survival, or ENACT. Members of the steering committee ranged from quiet lab types to veteran protesters such as Stephen Sporn, a member of the Students for a Democratic Society. Yet overall it was “a very conservative movement,” Russell recalled. “We put less emphasis on protest activism and much more on education and policy. We did not want to be seen as radical extremists, but rather as mainstream agents of change who were working through the ‘system.’ This point has been dramatically overlooked in many accounts. We discussed and scrapped plans for protests and banner-waving and sit-ins.”Declaring “Our sick environment needs you!” they called a mass meeting of interested students and announced plans for a massive, multi-day teach-in the following spring. And, right away, ENACT’s leaders began talking with staff in the office of U.S. Senator Gaylord Nelson (D-Wisconsin).

A poster from the U-M event that foreshadowed the Earth Day teach-ins of 1970. (Photo courtesy John Russell.)

Nelson had come to national prominence in the late 1950s as Wisconsin’s “Conservation Governor.” Elected to the Senate in 1962, he had spent the ’60s urging attention to the degradation of the American landscape—pollution, sprawl, littering, the loss of wilderness—but with little success. Now, the mounting squalor of water and air pollution was finally attracting press coverage and enflaming public worries. Nelson sensed a propitious moment. Just after touring the site of the Santa Barbara spill, he read an article on teach-ins as levers for political action. Within days, he was floating the idea of a nationwide teach-in on what people were calling “the environmental crisis”—at just the time ENACT was organizing in Ann Arbor.Nelson had a big idea, but he didn’t know much about teach-ins. So in November 1969, he brought in Doug Scott, a U-M student in natural resources and co-chair of ENACT, to help plan the national event, to be called Earth Day.

Scott brought to Washington a memo spelling out in detail the steps that ENACT had been taking to organize its own event. Nelson’s staff made copies and sent them out to anyone who asked how they, too, could take part in Earth Day.

Meanwhile, in Ann Arbor, the academic calendar was giving ENACT a problem. Senator Nelson had set the date of Earth Day as April 22, 1970, so that it would fall before final exam periods at most U.S. colleges and universities. But not at the University of Michigan, where, by the trimester system, April 22 would come smack in the middle of exams. ENACT had no choice but to schedule its event earlier. The organizers chose March 11-14. The event was formally titled, simply, the “Teach-In on the Environment.”

Events included speeches by Ralph Nader (above), Senator Edmund Muskie and biologist Barry Commoner. Though the activities were largely quiet and educational, there were symbolic protest actions too, such as the toppling of a gas-guzzling car (below). (Photos: Michiganensian. Courtesy Bentley Historical Library.)

That winter there were scattered pro-environment events on several campuses, including a one-day rally at Northwestern. But none matched ENACT’s ambition and scope. The organizers planned four days of events across Ann Arbor. They booked Crisler Arena for the opening night. They packed the speakers’ schedule with major names—Senator Edmund Muskie (D-Maine), the front-runner for the 1972 Democratic presidential nomination; social critic Ralph Nader; and Dr. Barry Commoner, an eloquent biologist who had become a guru to the emerging movement. They invited Hollywood celebrities who were worried about pollution—not young firebrands like Jane Fonda but old-timers like Arthur Godfrey and Eddie Albert—and industrialists who wanted to tell their side of the story. They got commitments from entertainers including Gordon Lightfoot, Odetta, and the Chicago cast of “Hair.” They planned field trips, clean-ups, rap sessions, movies, debates. Protests and demonstrations were planned, including a mock trial of a ’59 Ford that was to be smashed to pieces on the Diag. But most programs were to be genuinely educational, including workshops for some 20,000 elementary and secondary schoolchildren.But no one knew if the public would respond. As ENACT got ready for the first night’s events at Crisler, John Russell remembered, “We didn’t know if a thousand people would come or if 20,000 would come.” By the time the program started, organizers were scrambling to set up loudspeakers in the parking lot. Three thousand people had to stand outside. Over four days, an estimated 50,000 people took part in ENACT’s teach-in—an astonishing success that fueled enthusiasm for Senator Nelson’s national Earth Day, which drew some 20 million participants four weeks later and transformed environmentalism into a movement of historic importance. (A number of ENACT’s leaders went on to influential careers in the field, including Doug Scott, a longtime executive at the Sierra Club who is now policy director at the Campaign for America’s Wilderness; David Allan, who became a professor and associate dean of U-M’s School of Natural Resources and Environment; and John Turner, who served as director of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service under the first President Bush.)”The Michigan event was by far the biggest, best, and most influential of the pre-Earth Day teach-ins,” Adam Rome, a historian and authority on the environmental movement told the Ann Arbor Chronicle. “It was the first sign that Earth Day would be a big deal.”

Sources included John Russell; Alan Glenn, “The Turbulent Origins of Ann Arbor’s First Earth Day,” Ann Arbor Chronicle, 2/5/2009; “Gaylord Nelson and Earth Day: The Making of the Modern Environmental Movement,” Wisconsin Historical Society,

Comments

Colleen Clark - MPH 1969

I always tell eager people on the street with clipboards asking passersby to sign up for some environmental cause or other that I was at the first pre-earth day event. I was working in the Population Planning Center at the School of Public Health. My husband, John Clark and two fellow graduate students in the Geography Dept., Jack Eichenbaum and Howard Mielke, prepared a sound and light show, I think they called it, where they used slides they had taken, shown on two screens and with music, Beatles etc. It started out with two scenic pictures, one I remember was of a mountain in Norway reflected perfectly in a still lake (it was from our collection)and the Beatles “Here Comes the Sun.” Gradually the pictures became darker and more ominous with local pictures of pollution – my husband got chased away from Dow Chemical – and so forth. The music matched the pictures. It was very impressive and was shown several times.

Reply

Jerry de Gryse - 1974

I was a Senior in High School at the time of the first Earth Day and just happened to be on campus visiting my older brother. Earth Day changed my life and gave me the life long ‘green’ tinge that spurred me into Natural Resources and now Landscape Architecture. 40 years on I can say that Earth Day has made the planet a better place than it might have become. Many thanks to the organizers of the day and to my later teachers at SNR who gave me science to back p my passion. Regards Jerry de Gryse

Reply

Maralynn Kordich-Tanner - 1970

I was in Ann Arbor when the first Earth Day occurred and attended many of the gatherings. Students and faculty knew this was something special, something needed, something important. Yes, we do owe the organizers so very much for their insight and their fortitude. But it saddens me to think it’s 40 years later and even though there were improvements, there was still so much unaccomplished. I can only hope the present problems with the environment have truly re-started the cause in a strong way and the original organizers will see their plans come to fruition.

Reply

mike teeley - 71BS/UMD 74MS/SNR

This brings back many memories of the imapact some members of SNR, Jim Swan, Bill Stapp and Spence Havlick and oh yes who can forget Wally Rentsch had on the global effort to create a more environmentally aware America.

I attended one of the early organizational meetings as a junior from the sister campus, UM Dearborn. At that time we were a jr/sr only campus and most students paid little attention to anything that even looked like a cause.

From that meeting in AA we, a small group of students and a motivational Asst. professor, Dr. Orin Gelderloos, created a parallel AA type environmental teach-in that ultimately led to UMD become a focal point for environmental education in metro Detroit and was a source for significant environmental awareness for teachers and students across SE Michigan.

Today the Environmental and Interpretive Center on the UM-D campus is a model for grass roots organization and is an example of the leadership Michigan has long held in the area of environmental education.

I was personally funded in a titleIV grant to implement the Stapp model for environmetal education. It was disseminated to more that 5000 teachers in 100 schools,K-12, in Illinois. Teachers in 37 states purchased copies of our EE curriculum based entirely upon the Stapp model. It was the key reason I was Pesident of the Illinois Environmental Education Association.

From that small dedicated faculty at SNR Drs. Stapp, Jim, Spence, Bill Bryan and later Bunyan Bryant came a committed force of EE change agents who were guided and motivated to effect social and environmental change.

It was a great time to be in AA and associated with people who made a difference.

Reply

Jim Laramy - 1972

The caption to the first photograph states, “Reportedly, the students later picked up the cans and threw them away.” Not “reportedly”, I was one of the people who picked up the cans.

Reply

Thomas Higinbotham - MSU -79, CHS - 04

Great article. In 1970, I was in 9th grade at Barnum Jr. High School in Birmingham, Michigan…they had some sort of earth day program in the library…I got a UofM Environmental Teach-In Button….I still have it! I wear it every year….It’s a treasure to me…..thanks then, and thanks now!

Reply