Since even before U-M held the first-ever Earth Day teach-in, in 1970, the university has been producing environmental leaders. Many of them have played vital parts in the biggest environmental transformations of the past 40 years. We asked three of them to share their stories.

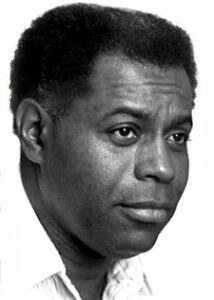

The advocate: Bunyan Bryant

In the summer of 1978, two young men drove a truck up and down rural roads in North Carolina, spraying oil from its tank onto the roadside. Laced through that oil were PCBs, industrial chemicals so toxic that they were about to be banned by the federal government. The father of these young men and his business partner had failed in a scheme to make money by collecting PCB-tainted waste oil, and now they owned tons of the stuff. Rather than safely disposing of it, which would have cost a fortune, the men rigged a nozzle to their tanker truck and dumped the oil on the ground.

Over a few weeks, they poisoned the soil in 14 counties.

Bad as it was, that crime would be forgotten today—except that it eventually sparked one of the biggest environmental battles ever.

Bunyan Bryant was on the University of Michigan faculty when that illegal dumping occurred. He and another professor, James Crowfoot, had been hired in 1972 to create the advocacy program for the School of Natural Resources. They researched and taught on subjects such as community organizing, and they brought environmentalists together with union workers, civil rights advocates, and other activists.

He had come to U-M in 1972, in the wake of two important events. First was the Black Action Movement strike of 1970, in which black students essentially shut down the university for more than two weeks. Among other things, BAM had won a pledge from the university to hire more minority faculty members.

The second event, Earth Day, sent enrollment at the School of Natural Resources soaring. Many students at SNR (it was later renamed School of Natural Resources and the Environment) clamored for faculty experts in advocacy and activism.

Bryant answered the calls for both minority and environmental advocacy faculty. He was one of nine new faculty members hired in to SNR, and he and Crowfoot (who would later become dean of SNRE) built U-M’s environmental advocacy program from scratch.

It’s fair to say that Bryant was the product of two distinct movements: civil rights and environmentalism.

He was perfectly placed to make sense of the movement that ultimately arose from that illicit dumping in North Carolina.

It wasn’t long before the contaminated oil was discovered and the perpetrators jailed. But then things got tricky: what was the state supposed to do with tons of toxic soil? North Carolina’s governor decided it should be excavated, then placed in a new landfill in predominantly African-American Warren County.

Residents protested the new landfill. When later studies found that PCBs had leaked beyond the landfill’s boundaries, the protests grew. Residents marched and blockaded soil-laden dump trucks with their bodies. Civil rights and environmental activists from across the country joined in, arguing that the siting of the landfill in a minority neighborhood amounted to racism.

Throughout the 1970s and ’80s, local environmental groups were popping up all over the country, often to fight waste sites in their neighborhoods. It soon became obvious that many toxic sites, such as Warren County’s, were located in poor and minority areas. Soon there was data to prove the point. A 1983 study by the US General Accounting Office (GAO) found that hazardous waste sites were disproportionately located in black communities. A 1987 study by the United Church of Christ concluded that nationally, the most significant factor in the siting of toxic facilities was race.

A new term entered the American lexicon: “environmental racism.” Today, those Warren County protests are remembered as the birthplace of its antidote, “environmental justice.”

“It did feel like a national movement,” says Bryant. “What was unique is that it was headed by people of color. That was the first time for the environmental movement.”

Bryant soon became a national figure in environmental justice. In 1990, he and SNRE faculty colleague Paul Mohai organized a seminal conference called “Race and the Incidence of Environmental Hazards,” inviting experts and policy makers to discuss the latest findings.

“People were so inspired by the conference,” says Bryant. “They said, ‘I never worked so hard in my life!'” Several participants remained in Ann Arbor to begin lobbying on the issue. They wrote to the heads of the EPA and other federal agencies, to the Congressional Black Caucus, to the mayors of every large city in the nation.

“There were other forces in the country” bringing attention to environmental racism, says Bryant, but that conference and the work it inspired “put environmental justice on the radar screen of the government.” Within a year, President George H.W. Bush’s EPA had established an “Environmental Equity Work Group;” and in 1993 President Bill Clinton issued an executive order to “address environmental justice.”

Those successes, Bryant says, were hard won. But they also meant that “people think things are set. And that kind of defangs the movement. Now there are still a lot of struggles in communities across the country, but they’re not being televised…. We should still have a movement, but it’s very hard to sustain a movement.”

Near the end of his career, Bryant remains animated by both civil rights and environmentalism. “We need to have sustainable communities,” he says. “The issue I have with sustainability is: sustainable for whom? It’s not really sustainable if it doesn’t address race, racism, structural inequality.” Despite the progress of the past, that remains a victory far from won.

The manager: Laura Rubin

“Laura Rubin is an iconic figure at the Erb Institute,” says Dominique Abed, a Marketing Communications Specialist at U-M’s Erb Institute—the home of the joint degree program between the School of Natural Resources and the Environment, and the Ross School of Business.

Rubin was the first graduate of the joint MS/MBA program, which gives students a chance to earn both master’s degrees in three years. Back then, the fledgling program was called CEMP: the Corporate Environmental Management Program.

Today, CEMP has become the Erb Institute, named for donors Fred and Barbara Erb. It’s home to 105 students and has become a national leader in building sustainable business.

But it wasn’t always that way. Rubin enrolled at SNRE when the joint degree program was still just a notion being discussed by Gary Brewer and Joseph White, the deans of SNRE and the Business School, respectively. While the program didn’t quite exist yet, says Rubin, “Brewer encouraged me that I should take classes in both schools.” She got special permission to enroll in core classes at the b-school.

It’s fair to say that the cultures of each school were alien—even hostile—to the other. That antagonism, Rubin says, reflected what was going on in the larger world. “‘Environmental’ positions in the corporate world were mostly window dressing. Companies would say they had a sustainability coordinator, but those people usually had little decision making power. They weren’t integrated into the management structure.” Likewise, nonprofits didn’t just distrust business, they often failed to understand or incorporate basic good-business practices like sound budgeting into their daily operations.

Rubin’s parents were both successful business people in the Chicago area, and she had majored in business economics as an undergraduate. But she had a passion for the outdoors and environmental issues, especially—growing up on the shore of Lake Michigan—in clean water. After earning her degree, she felt she had no choice but to make an either/or decision: go into the business world, or become an environmental advocate. She chose the latter, becoming an accountant and later an ocean ecology expert for Greenpeace. But “after a couple years of that, I was even more convinced that I wanted to be in both fields, and learn to speak both languages.”

Michigan was an obvious choice for graduate school. Its School of Natural Resources was one of the best in the country, it was located near her beloved Great Lakes, and there was a tantalizing possibility of taking rigorous business classes as well.

Once she started crossing between the two schools, says Rubin, she encountered a culture clash. “I felt out of place in both places,” she says, and frequently misunderstood.

“At the b-school, I was seen as the wacko. If we were talking about free trade—NAFTA was the big issue—and I’d bring up the environmental impacts of free trade, I felt I was dismissed. ‘Oh, she’s the one from SNRE. Oh, sure, she’d bring that up…’ I felt slighted and dismissed by some of the profs: ‘You don’t know what you’re talking about.'”

At the same time, she recalls an SNRE professor passing her in the hall and asking with a sort of jovial disdain, “What’s the prime rate today?” She says, “It clearly showed me that he didn’t understand the value of what we were doing if he thought it was all about things like the prime rate.”

That was then.

“There has been a massive cultural shift” in the 15 years since she graduated, says Rubin. The change is visible in SNRE, the business school—and the culture at large.

“Both sides realize now it’s not an either/or. Companies know that sustainable practice is good for the bottom line, and that they can thrive when they show good stewardship of natural resources…and environmental groups have a much better understanding of what corporations struggle with to become sustainable. It’s no longer, ‘You dirty rotten polluters,’ and more, ‘We have to find creative solutions together.'”Rubin herself went into nonprofit environmental management, using her business talents as she works on water issues as executive director of the Huron River Watershed Council in Ann Arbor. Having stayed local, she keeps in touch with the Erb Institute and its students, who inspire her. “The caliber of the students is incredibly high. Really smart people want to do this.” And those students are now supported with three full-time professors, internships, job services and a vibrant schedule of speakers, symposia and scholarship. “Each school sees the other as an asset.”

Better yet, “the demand for the training the Erb Institute offers is huge.” Where once there was hostility and misunderstanding between business and the environment, now there’s opportunity. “Business is really open” to sustainability, she says.

The result is that students with an environmental bent no longer have to go into advocacy work to express it. “Students want to find meaning in their jobs,” Rubin says. “They’re not taking their environmental values just into activism. They’re going into law, business, athletics… There are Erb graduates in insurance, education, big business, nonprofits, micro-lending…These are incredibly bright people, and they’re integrating their values into everything they do.”

The politico: Leah Gunn

“I attended the big Earth Day celebration at Crisler Arena,” says Leah Gunn. She had graduated from U-M ten years earlier, in 1960, with a BA in history and an MA in library science; after a stint in Madison, Wisc., she was back in Ann Arbor and active in state and local politics.

Forty years later, that first Earth Day looms large in the imagination, and for many activists it was a decisive moment in their lives and the movement. But to Gunn, it felt like one political event among many. “I was a home-maker with two little kids,” she recalls. “A friend came to town and said let’s go, so I went.” She remembers speeches by Wisconsin Senator Gaylord Nelson and actor Eddie Albert—but not an earth-shaking event.

“The crowd was enthusiastic and we all clapped,” she says, “and then we all went home.”

It would be a mistake, Gunn believes, to believe that Earth Day did—or could—change anything on its own. Instead, it was the hard work that led up to and especially followed it that really made a difference.

A librarian by trade (she worked at U-M’s graduate and law libraries) Gunn has been involved in local and state politics almost her entire adult life. She was elected Washtenaw County commissioner in 1996 and has been re-elected to the post six times. To her, that first Earth Day did not lead to immediate change. It revealed that environmentalism was a growing political force, but turning that energy into results still took years.

She points to the 1976 “bottle law,” which put a ten-cent deposit on many bottles in the hopes of reducing litter and promoting recycling, as one of the state’s first big environmental victories. “That was very controversial,” Gunn says. Passing it required six more years beyond the first Earth Day, and a massive statewide political campaign. Similarly, changes like curbside recycling programs, though they now seem to be a fundamental part of the social fabric, required political talent and will-power to implement.

Such programs and policies “took a lot of work to get through as legislation. Sometimes it took a vote of the people,” she says. Every environmental advance she’s been a part of in four decades, even those that seem like the obviously right choice, like recycling, has required hard work against strong opposition.

The virtue, to Gunn, of celebratory events like Earth Day is that they can show politicians that there’s public muscle behind environmental policies. “Public acceptance was there. People were willing to raise taxes on themselves to pay for these things.” Of that first Earth Day, she says, “I think it did help elect people who were aware of these issues, and they made their constituents more aware, and the constituents said yes.” In other words, she seems to say, the celebrations are nice. But it still takes a fight to get things done.

Sylvia Taylor - 1973

I was a grad student during the first earth day and one of the workers on the \”Huron River Walk\” event. One of the outcomes of the teach-in that most impressed me was the number of my fellow grad students in the Natural Science Building who shifted their career interests from the then \”hot\” topic of molecular biology to environmental careers rather than seeking academic appointments. My PhD was in Botany but I ended up as Michigan\’s endangered species coordinator.

Reply

Keith Heidorn - 1969

I attended the ENACT Events and we had a table. For the April Earth Day, I went back to my home town and lectured for two days on Air Pollution.

In the years since, I have worked in the Air Quality field, and organized three environmental conferences in Victoria BC.

I plan to write about those early days in my Almanac section of “The Weather Doctor” in April to mark the 40th anniversary.

Reply