Perfectly imperfect

Jim Abbott, who pitched for the University of Michigan from 1986-88 and in the Major Leagues for 10 years, accomplished much on the pitcher’s mound. He led Michigan to two Big Ten tournament championships. He won Olympic Gold in 1988. He received the Sullivan Award as the nation’s best amateur athlete. His number, 31, is retired at Ray Fisher Stadium. In 1993, he threw a no-hitter for the New York Yankees. He even once likened Bo Schembechler to Fidel Castro and lived, barely, to write about it.

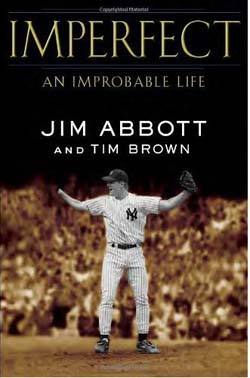

And yet, for all those accomplishments, his autobiography, Imperfect: An Improbable Life (Ballantine Books, 2012), written with Tim Brown, puts anxiety and imperfection at the center of the story. In that sense, Abbott’s book is as unusual among sports autobiographies as Abbott himself is unusual among top-tier athletes.

“Do you like your little hand?”

As baseball and Michigan fans know, Abbott is most obviously unusual for the fact that he was born without a right hand. Overcoming that physical obstacle was easy compared to overcoming how people viewed him and how, consequently, he struggled throughout his life to attain an integrated sense of himself. That struggle, rather than the ninth-inning nail-biters, is where the drama of Imperfect lies.

As baseball and Michigan fans know, Abbott is most obviously unusual for the fact that he was born without a right hand. Overcoming that physical obstacle was easy compared to overcoming how people viewed him and how, consequently, he struggled throughout his life to attain an integrated sense of himself. That struggle, rather than the ninth-inning nail-biters, is where the drama of Imperfect lies.

The book begins long after Abbott’s career has ended, as he visits his daughter Ella’s classroom on career day. He is recounting tales of his time playing with the California Angels, the New York Yankees, the Chicago White Sox, and the Milwaukee Brewers when one of the students asks him a question he has never asked himself: “Do you like your little hand?” And it’s not just any student who wants to know. It’s Ella.

“Do I like it?” Abbott writes. “I had never thought of my birth defect in terms of liking it. I’d disliked it some, found it a nuisance at times, hardly thought about it at others . . . Mostly my relationship with my hand and its various consequences was blurred, and often complicated. Its permanence bobbed in a current of all it might have taken from me and all that it offered.”

This is how a man who admits he spent a lifetime trying to fit in and avoid confrontation begins, prompted by his daughter’s question, to confront an undeniable fact of his life: the absence of something most of us have and take for granted.

Against all odds

The chapters of Imperfect alternate between Abbott’s personal history and the innings that marked his no-hitter at Yankee Stadium against Cleveland. It begins with the rigors of life in Flint, Mich., during the years of that city’s precipitous descent from working-class haven to Exhibit A in the decline of the manufacturing Midwest. A sociologist would not look at the circumstances under which Abbott entered the world in 1967 and bet that here was a kid who would beat the odds.

Abbott’s father, Mike, was playing high school basketball when he found out his girlfriend, Kathy, was pregnant. They were not yet married when Jim was born. As Mike and Kathy built a life together, Mike occasionally left. As Abbott writes, “They went through what people go through when they marry at 18, not really having the chance to experience their own adolescence. They lived apart for short periods, never more than a month or two. We’d live with Mom. And there was always reconciliation, happily.”

But Abbott’s parents were dogged. They found their way together through the world, and they were tenacious about seeing what they and the medical profession could do for their son. Then, perhaps even more importantly, after it became apparent that the medical profession could do nothing for Jim, they encouraged him to find out what he could do for himself. As a boy, Abbott hated the clunky prosthetic arm that inspired other kids to call him Captain Hook. He didn’t want to be different and certainly didn’t want to be pitied. The arm found its way to his closet floor and stayed there for years. His parents let it be. Abbott then found his way to the major leagues and stayed there for years.

Abbott’s memoir offers very little of the antic hijinks of, say, Jim Bouton’s Ball Four. Yes, there’s a piece of lunch meat that flies out of a Team USA bus window in Tokyo and finds the lap of a woman on the way to a wedding. And, yes, Abbott relates one instance in which a few too many 16-ounce curls exacted a heavy gastrointestinal price the next day. But for the most part, this is a book about a personable young athlete filled with respect for his teammates and a succession of mentors who viewed him, as he struggled to view himself, not as a one-handed pitcher but simply as a pitcher.

A league of his own

There are surprisingly few passages in which Abbott describes that state, known to professional athletes and a few lucky weekend warriors as “the zone,” in which mental processes and muscle memory merge for a few hours of athletic nirvana. Abbott certainly had his share of such moments. For every on-field triumph he recounts, however, there is an on-field failure—or, if not failure, a moment that amounted to something less than what Abbott desired as a competitor. As a backup quarterback in high school, he threw four touchdowns and led his team to a playoff victory. The next week he threw six interceptions in a loss. He finished the season of his major-league no-hitter with 11 wins and 14 losses.

Abbott is at peace with the fact that he was not a once-in-a-generation athlete on the order of Michael Jordan or Albert Pujols. He won 87 major league games and lost 108. He was 18-11 in his best year and 2-18 in his worst. Imperfect is about a boy who became a pitcher—not, as Abbott writes, a pitcher who was “pretty good, considering.” It’s about a boy who became a pitcher, and a pitcher who became a man.

About that no-hitter. Fifteen years later, Manny Ramirez, who had been a rookie with the Cleveland Indians in 1993, shrugged and said, “We hit some balls hard.” It was not a dominant no-hitter. Abbott walked more batters (five) than he struck out (three). The Indians hit a number of bullets that found Yankee gloves. The game was a grind. Abbott threw one pitch. Then another. Then another. He retired one batter. Then another. Then one more to finish an inning. He did that nine times. It was not a perfect game.

And that’s the point. Sometimes imperfection is as worthy of celebration and pride as perfection.