Six athletes discover what’s possible by daring to think big.

The Channel for ALS Team prepares to conquer. (Photo: Chris Hiltz.)

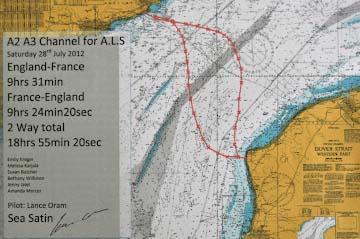

Just after midnight on July 28, the 36-foot motor cruiser Sea Satin bobbed along the English Channel, 650 meters off the English coast at Dover. The boat carried five members of a six-woman relay team from Southeast Michigan—extraordinary, ordinary women on a mission to set a world record and raise both money and awareness to fight a deadly disease.

The sixth, Emily Kreger, swam alongside, almost an hour into her fourth hour-long shift in the dark, choppy water. The team on the boat knew they were close to setting the record. Adrenaline overtook exhaustion, seasickness, and bone-deep cold as they screamed the time and distance to Kreger.

But a 30-foot breakwall blocked out the lights of Dover, and as she swam along in the dark, Kreger lifted her head out of the water and called, “I can’t see where I’m going.”

The women knew that somewhere out there in the darkness, a welcoming party waited on the beach. Teammate Jenny Jalet grabbed her phone and texted her husband, Sam: “Flash your phones so she can see you.”

Seconds later they saw lights on the shore—cell phones and camera flashes guiding them home. Kreger sprinted for the lights. She touched the English shore 18 hours and 55 minutes after the team first left it—a new world record for the women’s relay two-way crossing. They’d made it by four minutes.

Just Do It

“I was surprised at how unique and cool other people thought this was,” says Jalet, a former University of Michigan swimmer and LSA graduate who now works in the U-M athletic department. “We were very matter-of-fact, kind of like ‘Amanda organized this and we’re going to follow the plan and just do it.'”

Swimmers Emily Kreger, Melissa Karjala, Susan Butcher, Bethany Williston, Jenny Jalet, and Amanda Mercer once competed as college athletes. (Photo: Chris Hiltz.)

Amanda is Ann Arbor attorney and Channel relay ringleader Amanda Mercer. Back home, her neighbor Bob Schoeni marveled at her determination. A professor in the University’s Gerald R. Ford School of Public Policy, Schoeni has long been aware of the strong positive impact social connection can have on a person’s health and well-being. But he had no idea he would see it play out so vividly in his own life.

A devastating diagnosis

In 2008 Schoeni was diagnosed with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS, or Lou Gehrig’s Disease). There is no cure or treatment for ALS, and research is severely underfunded. At the time of his diagnosis, Schoeni’s friends and neighbors channeled their frustration into creating the nonprofit Ann Arbor Active Against ALS (A2A3) to raise funds and awareness. The English Channel swim is part of that effort, and has raised more than $90,000 to date. The women’s relay team is still taking donations at channelforals.org, working toward a goal of $120,000.

ALS gradually robs patients of the ability to move. In Schoeni’s case it began with weakening in his right hand, which he can no longer use. Now his left hand is beginning to weaken. He can still walk, but in the last couple of months, he says, he’s noticed his body seems to be changing more quickly.

But when he thinks about the swim, about the athletic commitment, the ambitious goals, the fact that these women squeezed training into lives already busy with careers and families—well, it means a lot to have good people in your corner.

“It gives me hope,” Schoeni says. “Not necessarily for a cure; given the speed of science the chance that there’ll be a major breakthrough in my lifetime is not great. But it’s given me the strength to push through and focus on the day. It’s allowed me to live a fuller life today and not get overwhelmed by the challenges I face.”

The old college try

Team leader Mercer swam just weeks after undergoing chemotherapy. (Photo: Chris Hiltz.)

“There were definitely times during training when I thought, ‘Why did I sign up for this?'” Jalet says. “And I’d stop and realize I had a choice. Bob doesn’t have a choice every day.”

Then in March, four months before the swim, Mercer was diagnosed with breast cancer. Her doctors told her they didn’t think she could do the swim—which only ensured she would. She dragged herself to the pool between rounds of chemotherapy.

“What makes Amanda so inspiring is she doesn’t have any sense that she’s inspiring,” says Jalet. “It’s that matter-of-fact attitude: ‘I have cancer and I’m just going to do this.'”

Chilling out

On a clear day in Dover, you can see France—a distant smudge of grey across the water. July 27 wasn’t one of those days. The swim started in rain at daybreak, when Kreger, a Detroit Medical Center surgical resident, former Yale swimmer, and onetime U-M graduate student, jumped from the boat and swam to Shakespeare Beach to wait for the start signal.

English Channel swimmers aren’t allowed to wear wetsuits, and the water temperature hovers around 60 degrees. The team had done a cold-water training swim in five-foot swells on Lake Huron; by comparison the Channel waves were relatively gentle—but the cold was much worse—breathtaking, painful, numbing cold. One hour in, five hours out, waiting for your turn to swim again and trying to get warm on a slow-moving boat where your best bet at avoiding seasickness is to stay outside in the elements.

“You never warm up,” says Melissa Karjala, a former U-M water polo player and graduate of the School of Public Health who now teaches and coaches at Cody High School in Detroit. “Usually if you move around for a while you warm up, but (in the English Channel) the warmest you’re ever going to be is when you get in.”

At its narrowest point the English Channel is 18.2 nautical miles (21 land miles) of cold water, strong tides, and fickle weather. Swimmers cope with seaweed, jellyfish, and floating junk while their guide boats lumber along through one of the world’s busiest shipping channels.

The reviews of the swim were unanimous: “Miserable.” “Horrible.” “Hardest thing I’ve ever done in my life.”

Jalet was the only one who says the cold didn’t bother her so much. That’s because she was too busy being seasick.

Says teammate Susan Butcher, an athletic trainer and former Eastern Michigan swimmer, “I’m glad I did it; it was an amazing experience, and it’s really cool to say we completed it and set a world record, but at the time it was not fun.”

Personal best

The swimmers started off at a record-smashing pace, and as Yale and U-M School of Public Health alum Bethany Williston made the turn at Cap Gris Nez, France, they thought Mercer, the final swimmer in the rotation, might not even have to swim a third time. But on the return trip, the Channel for ALS team didn’t hit the tides quite right. With daylight fading, the Channel turned choppy and cold, and Mercer’s turn came around again.

Jumping off that swim platform, she says, was the hardest thing she’s done in her life—the culmination of all that she’d been through over the past four months.

“Personally, jumping into the water for that third swim was much more of a triumph for me than setting a world record,” Mercer says. “I really kept talking to myself about Bob, about how this is nothing compared to what he’s going through. Telling myself, ‘You just have to go 45 more minutes. Suck it up, Amanda.'”

Former Michigan water polo player Karjala marks the team’s time at Dover’s White Horse Inn. (Photo: Chris Hiltz.)

By the time Sea Satin docked, it carried a very subdued group of world-record holders. Between that final push for shore and the screaming, hugging, and crying that followed, they could barely stand. Eventually they would visit Dover’s White Horse Inn, where successful Channel swimmers record their times on the walls.

About 1,290 solo swimmers and 782 relay teams have successfully swum the Channel since the first unassisted crossing in 1875. The vast majority of swimmers cross the Channel just once.

“The thing that really hits home to me was when I heard about all the people who were following along, reading Twitter, following our GPS,” says Michigan alum Karjala. “To me that’s what made it most real, knowing those people were with us on the boat.”

Think Big, No Matter What

On August 14, a team of women from the Netherlands broke the Americans’ record with a two-way time of 18 hours, 21 minutes, and 30 seconds.

When Mercer found out, she had a moment’s urge to go back when she’s healthy and strong and break it again. But the moment passed. Setting the record was nothing compared to learning how much the swim meant to people who’d lost loved ones to ALS, she says. Losing the record? Well really, what have they lost? Nobody un-swims the Channel.

“Amanda thinks big,” Jalet says. “I don’t tend to think big, so when she would throw out numbers like $120,000, when she would throw down, ‘Let’s set a world record,’ that was very daunting.

“I’ve learned that when you think big you can do more than you have ever imagined.”

Ruth Stone Feldman - 1960

Wonderful, heartwarming, inspiring achievement! Makes me so proud of -and feel one with- these women, Michigan graduates, nurturers, passionate people who are making a difference for good!

Reply

Tracy Dennis

I can only say I am truly inspired and aw stuck by these women. Sharing their story has made my own battles seem less daunting. Thank you!

Reply

Muffy MacKenzie - 1985

These women are true heros! Let us all honor them, Prof. Bob Schonei and all of those who are suffering with ALS by showing our support and making a pledge channelforals.org. I bet the UM community can make that $120,000 goal happen!

Reply

Kelsey Hargesheimer

Please note that both Karjala and Williston were graduated from the U-M School of Public Health! We at SPH are extremely proud!

Reply

terry provenzano

Nice that they would help a friend with ALS but, aren’t these walks, swims, runs, becoming horribly elitist and repetitive? We need some fresh thinking, not the same warmed over baked goods!

Reply

Kelly Scholten (Yakemonis)

What a beautiful story of overcoming obstacles! Your dedication to your friends and each other is powerful. Congratulations! A world record is something to be proud of…surely not “warmed over baked goods” (as one of the comments states). It is the culmination of years of training and sacrifice. In the face of disease, especially ALS, where a person is powerless and becoming even more so, this is a way for loved ones to gather together and show solidarity and love. Triumph of the human spirit is never an old story; but one of renewed hope for us all.

Reply