They call each other Nealie and Margie, but for decades, others had a different way of addressing Cornelia Kennedy and Margaret Schaeffer: Your Honor.

Kennedy, ’47, has been called the “First Lady of the Michigan Judiciary” for being the first woman appointed to the federal bench in Michigan, and just the fourth woman in the nation to be appointed a federal district court judge, in 1970.

Her sister, Schaeffer, ’45, was sworn in as a judge five years later in the 47th Judicial District in Farmington Hills.

“We were the first sisters to serve as judges anywhere in the country,” Schaeffer says.

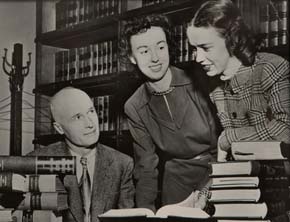

The former judges inherited much of their love of the law from their father, Elmer Groefsema, a 1917 graduate of the Law School. (Image courtesy of Kennedy and Schaeffer.)

It’s a feat that surely would have made their father and mother proud. The girls (along with sister Christine Gram, who went on to become president of Oakland Community College, Auburn Hills Campus) were raised by father Elmer Groefsema after their mother, Mary, died unexpectedly when Margaret and Cornelia were 11 and 9.

They inherited their love of the law from both parents; their father, a 1917 graduate of the Law School, was a distinguished Detroit trial lawyer, and their mother had been taking classes part-time at Michigan Law prior to her death.

Their father thought all three of his daughters should go to college, and he firmly believed that they should not necessarily be steered toward careers in teaching or nursing, as was the case of many educated women at the time.

After attending U-M for their undergraduate degrees, both women attended Michigan Law. Schaeffer was one of two women in her small wartime class, while Kennedy was one of fewer than 10 women in a much larger class two years later. “I remember having to meet with all the other girls in the lobby—not just because we were women, but because the JAGs took all the meeting rooms,” Kennedy says, referring to the Judge Advocate General School that operated at Michigan Law during World War II when she began her studies here.

After law school, the sisters clerked for judges and then joined their father’s practice in Detroit. It was a time when being a female lawyer was still a novelty to some; during their clerking days, neither sister saw a woman argue a case. Both of them remember having lonely, solo lunches during the early years of their careers. “Women just didn’t ask men to have lunch with them,” Kennedy says.

Clients, too, were thrown off. “A lot of times, you’d get a call and they’d say, ‘Put the lawyer on the phone,’ assuming you were the secretary,” Schaeffer recalls. “Now there are enough women lawyers that they don’t do that anymore.”

Sisters Cornelia (left) and Margaret were honored at the 75th annual meeting of the Women Lawyers Association of Michigan.

One New York firm even told Kennedy that it hired women during the war, but “too bad for me, the war was over,” she says.

After their father’s death in 1952, Kennedy moved on to Markle and Markle in Detroit. Schaeffer joined her in 1954, following the birth of her second child. In 1966, Kennedy was elected to the Wayne County Circuit Court, where, she learned, the pension system would not benefit the husband of a woman judge unless he was dependent on her at the time of her death (a restriction that did not apply to widows). In 1970, when she was appointed to the federal bench by President Nixon, she learned there were no pensions for the husbands of women federal judges. In both instances, she successfully worked to change the rules that were designed in an era before women were judges.

After seven years on the bench, Kennedy rose to the rank of chief judge of the Eastern District, becoming the first woman to be selected as chief judge of a U.S. District Court. Then, in 1979, President Carter nominated her to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit. Kennedy still laughs when recounting Senator Orrin Hatch’s reaction to her during confirmation hearings: “By damn, you have a lot of qualifications.”

Those qualifications put her on the short list for the U.S. Supreme Court. President Reagan narrowed his search to just two people in 1981: Kennedy and an Arizona judge named Sandra Day O’Connor, one of whom would become the first female justice. Many thought Kennedy would be the choice; Senator Strom Thurmond “kind of adopted me, urging for my appointment,” Kennedy says.

In the end, O’Connor was chosen. “I was somewhat disappointed, but, you know, it’s a political situation. I was five years older, which was a factor, as I understand it. I quit thinking about it because there’s no purpose in it,” Kennedy says.

The Honorable Cornelia Kennedy, ’47 (left), and The Honorable Margaret Schaeffer, ’45, now retired, continue to live near one another in suburban Detroit. (Photo: Martin Vloet, Michigan Photography.)

Schaeffer says she learned a great deal about being a judge from her younger sister. She put that knowledge to good use starting in 1974, when she won the election to become a judge in the 47th Judicial District in Farmington Hills. She went on to become the chief judge of the district.

Schaeffer also raised four children, and Kennedy raised one. Schaeffer describes the work-life blend as a “neat balancing act,” and says she was heartened when her 7-year-old son wrote this for a school assignment: “I am thankful for my mother because she is a lawyer and earns money for toys and taxes.”

Both women are masters of understatement and humility. After a long and distinguished career, Schaeffer talks more about her sister’s achievements than her own. And Kennedy, with her long list of firsts, sums up her career this way: “Well, you just do it. You just go to work and do the job.”

When pressed, she adds: “I guess some people have said or written that I influenced them. It’s been a great career.”

This story first appeared in the fall 2012 issue of Law Quadrangle, the Law School’s alumni magazine.

Gayle Boesky - 1969

As an attorney. I have appeared before both Judge Kennedy and Judge Schaefer. There are three qualifications in judges that I believe are important. A judge should be prepared, open minded, and be willing to make a decision. Both of these judges passed with flying colors.

Reply

Mary (Driver) Weatherhead

Thanks for the article on the Groefsema sisters. I was at Michigan when “Corny” was there and remember her as a great person. Also appreciated the story about Dean Alice Lloyd. took me back several years!

Mary (Driver) Weatherhead, BBA, 1945

Reply