For the first time, scientists have identified how much pain people feel by looking at images of their brains.

The findings, published in the New England Journal of Medicine, may lead to the development of methods doctors can use to objectively quantify patients’ pain.

Pain intensity is usually based on patient self-reports, using an intensity scale from one to 10. Objective measures of pain could confirm those subjective reports and provide clues about how the brain registers different types of pain.

The new research also may set the stage for using brain scans to objectively measure anxiety, depression, anger, or other emotional states.

“Right now, there’s no clinically acceptable way to measure pain and other emotions other than to ask a person how they feel,” says Tor Wager of the University of Colorado and lead author of the paper.

Co-author Ethan Kross, a psychologist and faculty associate at the U-M Institute for Social Research, adds, “These findings demonstrate it is possible to accurately predict people’s experience of an incredibly complex psychological state—an emotional response—based on neural activity alone. [The findings] raise the tantalizing possibility that it may be possible to predict the experience of other types of complex emotional responses—depression or anxiety, for example—using similar methods.”

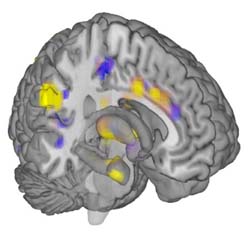

Wager, Kross, and colleagues used data-mining techniques to comb through images of brains taken when the subjects were exposed to multiple levels of heat, ranging from pleasantly warm to painfully hot.

“We found a pattern across multiple systems in the brain that is diagnostic of how much pain people feel in response to painful heat,” Wager says.

Initially, the researchers expected that pain signatures would be unique to each individual. If that were the case, a person’s pain level could only be predicted based on past images of his or her individual brain. Instead, they found the signature was uniform across people. This uniformity allowed researchers to accurately predict how much pain the applied heat caused each person, with no prior brain scans needed as a reference point.

The scientists also demonstrated the signature was specific to physical pain. Past studies have shown social pain can look very similar to physical pain in terms of the brain activity it produces. For example, a prior study conducted by Kross, Wager, and colleagues showed the brain activity of people who have just been through a relationship breakup—and who were shown an image of the person who rejected them—is similar to the brain activity of someone feeling physical pain.

But when Wager’s team tested to see if the newly defined neurologic signature for heat pain also would pop up in the data collected earlier from the heartbroken participants, they found the signature was absent.

“Although social and physical pain are clearly related in terms of the specific areas of the brain they recruit, distinct patterns of neural activity or neural signatures may predict each type of experience,” Kross says.

Finally, the scientists tested to see if the neurologic signature could detect when an analgesic was used to dull the pain. The results showed the signature registered a decrease in pain in subjects given a painkiller.

The results of the study do not yet allow physicians to quantify physical pain, but they lay the foundation for future work that could produce the first objective tests of pain by doctors and hospitals. To that end, Wager, Kross, and colleagues are testing whether the neurologic signature varies with different types of physical pain.

The research team also included Mathieu Roy and Choong-Wan Woo of the University of Colorado, Lauren Atlas of New York University, and Martin Lindquist of Johns Hopkins University.

The study was funded by the National Institute on Drug Abuse, the National Institute of Mental Health, and the National Science Foundation.

Richard Fidler - 66,71,87

Measuring pain by observing brain structures “light up” under physical stimulation does not necessarily connect with the subjective experience of pain–or does it? What if brain imaging indicates pain when other physical markers–pulse, breathing rates, hormone levels–do not reflect the experience of pain? Meditators might be able to block the expression of pain at that level–or do they suppress pain at pain centers in the brain directly?

On the other hand, what about people who do not have pain centers “light up” to any great degree and still report considerable pain? Where does their pain come from? Saying it is “made up” answers no questions at all. The point is that the subjective experience of pain can be very different from objective measures gathered from brain scans.

Reply

Adrienne Ressler - 1964,1966

I am very interested in this article but found the first sentence quite misleading due to its sentence structure,”For the first time, scientists have identified how much pain people feel by looking at images of their brains.” It appears that the writer is saying that people feel pain when looking at images of their brains. While that might, indeed, be true, there is no mention of it in the article. What happened to English 101?

Reply

Donald Marks - 1980

This is hardly the “first time!”. I published on the same in 2010 (Marks DH, Valsasina P, Rocca M and Filippi M. Case Report: Documentation of Acute Neck Pain in a Patient Using Functional MR Imaging. Internet Journal of Pain, Symptom Control and Palliative Care [peer-reviewed serial on the Internet]. 2010, Vol 8(1)) I also cite research dating back to 1995 (David).

Reply