Author Ken Magee, at age 10, shakes hands with Michigan All-American and captain Ron Johnson, 1968. (Image courtesy of the Ken Magee Collection.)

As a kid growing up in Ann Arbor, Ken Magee would bring a slim plastic sleeve to every Michigan football game he attended. The sleeve was sized to hold the game program, which the young collector saw more as an artifact for preservation than a guide to the day’s activities. As his passion for Michigan football grew, so did Magee’s collection of memorabilia. Ultimately, he opened a store in Ann Arbor and today, many of his personal items are on loan to the Towsley Family Museum in Schembechler Hall.

Among Magee’s favorite items are those related to the rivalry with the University of Minnesota Gophers, dating back to the first contest on Oct. 17, 1892. It is the subject of the new book The Little Brown Jug: The Michigan-Minnesota Rivalry (Arcadia Publishing, 2014), co-authored by Jon M. Stevens (M. Arch.), with a forward by Glenn E. Schembechler III.

For the authors, the story really begins in 1903 when Minnesota custodian Oscar Munson found Michigan’s discarded water jug in the visitors’ locker room. The discovery came after a bitter contest in which Minnesota dominated the Wolverines in almost every statistical category except one: points. The game ended in a tie after Minnesota scored a touchdown with two minutes left on the clock. Exuberant fans stormed the field, forcing an early end to the game, which many football pundits considered a major upset over the Wolverines. It was Fielding Yost’s first “defeat” as head coach at Michigan. It was also the first live “broadcast” of a college football game.

Misnomer?

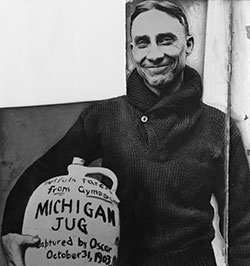

Custodian Oscar Munson found the jug discarded by the Wolverines after the 1903 game. This photograph was taken after Doc Cooke had painted the jug and forever memorialized Munson’s place in college football lore. (Image courtesy of U-M’s Bentley Historical Library.) View slideshow.

People may not realize the five-gallon jug was neither little nor brown. It was 16 inches tall with a circumference of 37 inches. It was a putty-colored ceramic jug in the style produced by the Red Wing Stoneware company, and weighed more than 20 pounds. Munson brought the jug to Minnesota Athletic Director Dr. L.J. “Doc” Cooke, who painted it to read “Michigan Jug, captured by Oscar, October 31, 1903.” Cooke also painted the final score: “Minnesota 6” in oversized text, and “Michigan 6” in a much smaller script, and hung the jug from his office ceiling.

When Michigan prepared to return to Minnesota’s Northrop Field in 1909, Cooke had an idea to generate more spectator interest in the game. He proposed to Yost the idea of challenging Michigan to win back their water jug. Of course, Yost agreed.

Thus began the trophy’s own life story, which has been the subject of much exaggeration and folklore over the years. Magee and co-author Stevens worked closely with Michigan football historian Greg Dooley to confirm and refute a number of myths that grew up with the jug over time. The tales are interwoven with a rich array of game stats, player histories, trivia, and other facts.

The photo-centric book features several images from the Minnesota archives, as well as photos from U-M’s Bentley Historical Library and Magee’s own collection. And if a picture paints a thousand words, it is clear the Little Brown Jug has inspired more than its share of passion, excitement, and jubilation as it traded hands over the years.

In 1920 the jug was painted brown, with room for each school’s signature “M” and a running tally of scores dating to 1903. It even has its own special case. Today there are all sorts of trophy rivalries in college football, but there can only be one “first.”

And so it goes. . .

As with any great drama, the cast in this story includes countless colorful characters, from Coach Fielding Yost, who Magee describes as a sort of “P.T. Barnum of college football” to legendary players like Tom Harmon, who always regretted that he never won the jug. There are also props, including pins, pennants, programs, and more.

For Stevens, it was a kick to mine the archives for images of players on both sides hoisting the jug with palpable joy. “There’s no other trophy like it. It’s more than a football game. It’s more than a rivalry. It’s history,” he says.

In recent years the Minnesota rivalry has taken a back seat to other classic Michigan rivalries with Ohio State, Michigan State, and even Notre Dame. But there’s something about the Little Brown Jug that continues to captivate fans, players, and coaches on both sides of the gridiron.

“It serves as a great rallying point; coaches over the years have used it as a focus for motivation,” Magee says. “It’s a property. It’s a tangible item. It’s an heirloom that belongs in ‘your family.’ You do not want anyone to come in and steal your grandfather’s pocket watch. Nor do you want them to come in and take ‘your family’s jug.'”

In the course of producing the book, the authors met with Michigan equipment manager Jon Falk, now retired, who allowed them to “hang out” with the jug itself. It was a rare and unforgettable thrill few fans get to experience, Stevens says.

“Jon was so respectful; he loves the jug,” says Stevens. “When he pulled it out of the case, I have to admit, we got a little giddy. It was a very special moment.”

Magee is a 30-year veteran of law enforcement, retired federal agent with the Drug Enforcement Administration, and former chief of police for U-M. A portion of the book’s proceeds will benefit the Ken Magee Foundation for Cops, which assists police officers who have been permanently injured in the line of duty and their families. Stevens is a designer for an architectural firm in Ann Arbor.

(Images above are reprinted courtesy of the publisher.)