Spring fever

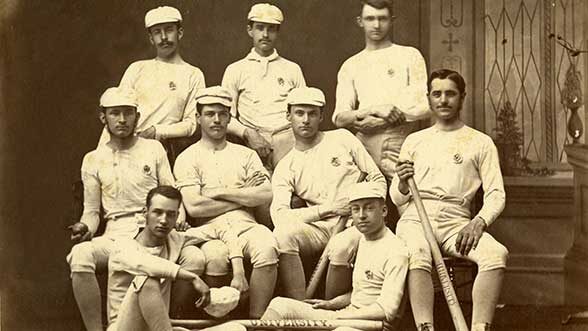

The Wahoo Base Ball Club of Dexter, Mich., vs. the Ann Arbor Base Ball Club, 1865. (Edith Wheeler Photograph Collection, courtesy of U-M’s Bentley Historical Library.) Larger image.

In the wartime spring of 1863, a Michigan freshman named Jack Hinchman strolled out to a broad patch of level turf just north of the Diag and took a careful look at the ground.

The snow had melted. He saw green sprigs of grass. He estimated rough distances. Then he paced off the four sides of a diamond.

Next he bought balls and bats, rounded up some buddies, and declared that the University of Michigan’s first baseball team was ready to play.

Hinchman had caught the craze in his home town of Detroit, where baseball was suddenly all the rage, as the historian Peter Morris relates in Baseball Fever: Early Baseball in Michigan (University of Michigan Press, 2003).

For years, American kids had played a bat-and-ball game called “rounders” at barn-raisings and town meetings. Then, in the 1850s, young men in New York and Boston tightened up the rules to create a new game they called “base ball.” It was clean, outdoor fun and it spread quickly to the New Yorkers and New Englanders who had settled the Midwest.

“An American Game”

This unidentified member of the 1875 U-M baseball team certainly had a flair for fashion. (Courtesy of U-M’s Bentley Historical Libary.) Larger team image.

“Base ball is strictly an American game,” The Detroit Free Press declared in 1860, “and is fast becoming popular, as it well deserves. There is no healthier amusement in vogue, and the time spent in practice is so much time taken from pursuits that may be far less moral in their tendencies.”

It could be played for sheer fun in “muffin games” — named for all the fly balls and grounders that casual players “muffed” — or it could be played by strong, steely young fellows determined to win against rival towns.

In Detroit, the best players — including young Jack Hinchman and his brother, Ford — belonged to a ball club called the Brother Jonathans. On July 4, 1862, they creamed the Ann Arbor Monitors on an impromptu field on the Diag.

That fall, Jack enrolled as a Michigan student, and by the following spring he was the University of Michigan Base Ball Club’s president, captain, and catcher. “I play Base Ball two or three times every week,” he wrote his family.

It was arguably U-M’s first organized sporting activity. The president of the class of 1861 recalled that during his years at U-M, just before the Civil War, “there were no athletics … no foot-ball, no base-ball, no track-teams … no set games of any kind … just a little plain country play for fun.” After all, most of Michigan’s first students had been farm boys whose out-of-school hours were spent in their parents’ barns and fields.

But that was starting to change as more kids like Hinchman, raised in the nation’s fast-growing cities, came to Ann Arbor to go to school.

“Base Ball for Breakfast”

They played high-scoring games against new clubs springing up in all the nearby towns — Ypsilanti, Dexter, Jackson, Marshall, Monroe, Adrian. Newspapers trumpeted the competitions and said the new pastime built character.

“Our young men are determined to be up with the times,” wrote the Tecumseh Herald. “Amusements of some kind are necessary to complete development of man’s physical and intellectual nature, and hence all innocent amusements should be encouraged. Among such we class a Bass [sic]Ball Club.”

Athletes work out in Waterman Gymnasium, 1910. (Image courtesy of U-M’s Bentley Historical Library.) Larger Image.

With the end of the Civil War in 1865, homecoming soldiers — some of whom had played a few innings now and then near southern battlefields — swelled the ranks of rival clubs, and the competition for bragging rights blazed.

“Amateur clubs have started up in every direction,” the Chicago Tribunereported in 1867, “and now base ball threatens to absorb every other theme of public interest. It is base ball for breakfast, base ball for dinner, and base ball for supper.”

The U-M Club was especially strong that year. Interest ran so high that somebody chopped down University trees to enlarge the outfield. Lewis Goddard, the ball club’s student president, had to apologize, saying the axe-men “had more in mind the interests of ball players, center fielders in particular, than the worth of the trees or the feelings of the authorities.”

On June 15, the U-M nine — including Eugene Cooley, son of the Law School dean — traveled to Detroit to take on the mighty Detroit Base Ball Club, successor to the Brother Jonathans. The U-M boys were heavy underdogs. But they ran away with the game.

Michigan’s catcher, George Ellis Dawson, hit four homers and scored 11 runs. But that was a mere fraction of U-M’s total. The final score was U-M 70, Detroit 18.

“Wielding the Willow”

In 1906 intercollegiate activities shifted to the north part of Ferry Field. The baseball diamond moved north to the present site of Yost Field House. In 1923, with the erection of Yost Field House, the baseball diamond moved west to its present location. In 1914 the wooden stands from the south side of the football stadium moved to the diamond. (Image courtesy of U-M’s Bentley Historical Library.) Larger Image.

In our 21st century, when musclebound millionaires run the bases, spring tends to bring nostalgia for baseball’s long-lost innocence. In fact, that nostalgia is nearly as old as the game itself. Even in 1868, scribes were mourning the loss of the game they once had known.

That spring, the student editors of the U-M Chronicle,forerunner of The Michigan Daily,warned that baseball was being corrupted by the ethic of winning-above-all.

“Warm breezes and clear skies” had come again to Ann Arbor, the editors noted. “Base balls fly from hand to hand in the campus and in the streets, bats are brought out from winter quarters, and canvas shoes are everywhere to be seen … Everyone who knows the life and character of students must rejoice to see them interested in a game so promotive of health and muscle.”

Yet in too many places, “rowdies and bullies” had crowded gentlemen out of the sport, and “the desire to obtain a gilded ball led men to depart from the path of honor and to use improper means to gain the honor.”

The same theme echoed some 15 years later, when Michigan named its first official varsity team and joined the new Inter-Collegiate Baseball League.

The local press covered every game — and hankered for a more authentic, pure rite of spring.

“What is the object of a college nine?” a writer for the local Michigan Argonautasked. “The average college student does not take up base ball with an idea of following it as a profession; but weary with study, he seeks fresh air … by wielding the willow.”

Sources included Peter Morris, Baseball Fever: Early Baseball in Michigan (2003) and Rich Adler, Baseball at the University of Michigan (2004). Thanks to Greg Kinney and Brian Williams of the Bentley Historical Library.

(Top image: The 1875 U-M baseball team. Photo courtesy of U-M’s Bentley Historical Library.)

Note: The title of this article has been revised since its original publication on 4/17/15.

Trevor Taylor - 1995

And now UM baseball games are played with blaring rock & roll and rap music. It is so bad that it’s played as the batter walks to the plate, as he practices a swing – then it cuts off just for a few moments as the pitches are delivered – then resumes. The whole experience has been cheapened and has gotten too far from waking from a Winter slumber and attending a game to hears the sounds of Spring & Summer: the players taking the field, the sound of the ball, the gloves, the bats and so on. But long live UM Baseball – what many believe to be the one & only sport at the University. Go Blue!

Reply

Jim Hallett - 1972

Of course, the sound of baseball is altered forever, as the college game uses the damn aluminum bats. The glory days of UM baseball are long gone, as it is a WARM weather sport, so all the best players will head to the SEC, Pac 12, and Texas, rather than battle the wind, rain, sleet, etc. of a “spring” in the Midwest. I enjoy reading about the history, and it is my favorite sport, but on the college landscape, it gets buried with a lot of other lesser sports, as football & basketball get all the press.

Reply

Jon Van Hoek - 2000

Great article! If anyone is interested in seeing 1860 base ball come to life, come check out the Monitor Base Ball Club of Chelsea–we’re beginning our fifth season here in Chelsea, and we’re one of about 30 amateur clubs in Michigan playing baseball by Civil War-era rules. Home matches are played at Timbertown Park on Sibley Rd, and they are free and family-friendly. We also play at Greenfield Village and around the state. For schedule and more info, you can send me an email at: chelseamonitorbbc@gmail.com or check out http://www.facebook.com/ChelseaMonitors. Several other UM grads in addition to myself on the club.

Reply

Vanessa Prygoski - 1990

Michigan baseball does quite well, considering the disadvantages that northern teams face. Even better than baseball in recent decades has been the Michigan softball team, led by the woman who is in my humble opinion the best coach the University has ever had in any sport — Carol Hutchins. And actually, no less a Michigan legend than Bo Schembechler once referred to Hutch as “the best coach on this (expletive deleted) campus!” Hutch’s teams dominate the Big Ten and the Midwest and north more generally, and hold their own against teams from the warmer parts of the USA. And their 2005 national title remains the only one won by a northern team.

Reply