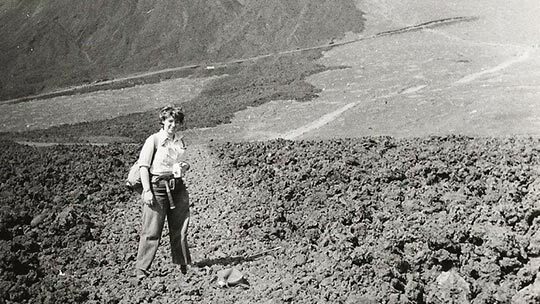

Woman in the field

When Helen Foster was a teenager in Adrian, Mich., — this was in the early 1930s, when her dad was running an insurance business — what she wanted more than anything else was to hunt for whitetail deer.

She was an old hand at fishing and camping. She’d been doing those things with her family since the age of four. With her mother, she’d spent hours engrossed in the tales of Roy Chapman Andrews, a hero-explorer who enchanted readers with books like Across Mongolian Plainsand On the Trail of Ancient Man.In young Helen’s mind, taking to the woods with a deer rifle would be the closest a small-town Michigan girl could get to an expedition with Andrews.

But when hunting season came around, school was always in session. So the answer from her parents was always no, she couldn’t hunt until she finished school.

Then, before she graduated from Adrian High, her father died. The long-promised hunting trip was never to be. Instead, Helen Foster took up the study of geology at U-M, which led to a life of outdoor adventure very far indeed from the woods and fields and whitetail deer of Lenawee County.

Geology goes to war

Her father’s death left the family with little money in the midst of the Great Depression. So Foster earned a scholarship to U-M and worked her way through school. Her mother suggested a course in geology, and after two weeks in class, Foster was nuts about rocks. She spent a summer at U-M’s Camp Davis, the geology field station near Jackson Hole, Wyo., and the pattern of her career took hold. She would become a field geologist.

This Camp Davis team in 1896 long predates Foster. (Image courtesy of U-M’s Bentley Historical Library.)

Foster started her pursuit of a PhD in the fall of 1942. Male students were deserting the campus for service overseas, and Kenneth Knight Landes, chair of the Geology Department, was worried that Camp Davis might have to close. So Landes conjured the idea of a concentrated summer training program for women who would specialize in petroleum geology — finding oil, that is, a critical wartime need — and Foster helped him to set it up.

But she was a geological generalist. She didn’t want a career in finding oil. So in 1947, after a teaching stint at Wellesley College, she got a job at the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS), the old-line federal agency that had charted the American continent.

The job was in USGS’s Military Geology Branch. With World War II over, the U.S. needed precise maps of the sprawling Pacific island chains of the Japanese Mandate.

Helen Foster was going to be an explorer.

Mapping the terrain of the Cold War

She crossed the Pacific sitting on a canvas bench in a military transport plane. For her first months in Japan, she toured research libraries and consulted experts, compiling a bibliography of everything known about the geology of the Mandate islands — the Marshalls, the Marianas, the Ryukyus, Micronesia. She saw Gen. Douglas MacArthur, chief of the U.S. occupying forces, arrive for work every morning. She toured the scientific laboratory of Emperor Hirohito and in time met the emperor himself.

Then Foster set out on her first mapping assignment — the Ryukyu Islands, stretching south from Japan almost to Taiwan. She and the other geologists would be the first to make detailed studies of the physiognomy of these remote places — their geologic make-up; their mineral deposits; the contours of their slopes; the water courses; the exact shape of their coastlines. The U.S. was fighting the Cold War now, and it needed to know the extended neighborhood of its new enemies, the Soviet Union and Communist China.Foster spent several years in that chain and became chief of the crew that mapped the volcanic island of Ishigaki. For a year-and-a-half, she lived in a tiny bungalow overlooking a lagoon, with an abandoned Japanese war dog for company. She spent one night lost in a jungle. On assignment in Okinawa, she was told to pack a pistol to ward off renegade soldiers.

And in her spare time, she developed a lifelong hobby — volcano watching.

Northern exposure

In all, Foster spent nearly 10 years based in Japan. Then, in 1957, she went home to compile reports of all her work. But her wanderlust persisted, and in 1960, she joined the Alaska Terrain and Permafrost Section of USGS’s Military Geology Branch. Her first task was to map the terrain for the U.S. Army’s winter maneuvers.

Often Foster worked with just a single assistant. In the morning, a helicopter would carry them to some distant quadrant that Foster needed to study — say, an undocumented outcropping on a mountain. They would work all day in the middle of the deepest wilderness. Then, just before nightfall, the helicopter would return and pick them up — usually. An occasional unplanned night in the bush, sharing the woods with moose and bear, came with the job.

In 1969, Foster was dropped off with her assistant, a younger geologist named Jo Laird, to study a gravel bar in Fortymile River, a tributary of the Yukon. It was August, but after several days, rain turned to snow, and when their bush pilot landed to pick them up, he couldn’t get airborne again.

On his last try, a down-draft sent the plane into the river at the end of the gravel bar, and frigid water rushed into the cabin. The group squeezed out and waded to shore, but by then the plane was stuck on the river bottom. They were a two-day hike from the nearest airstrip, and the pilot was both out of shape and limping on an injured knee.

The trio set off on caribou trails through snow that was two feet deep in spots. On her map, Foster spotted a mining camp not far off. It would be closed up and empty at this time of year, she knew, but they might find shelter and food.

Sure enough, they made it to the camp, broke into a cabin, lit a fire, and shared Spam and a can of soup. The next day they made it to the airstrip at a place called Chicken — not hardly.

“Go ahead and start out…”

Foster retired from the USGS in 1985 and moved to Carson City, Nev., where her sister lives, too. At age 98, she maintains many contacts in geology circles.

In all her travels she never encountered discrimination on account of her sex, she said recently.

“One thing that may have made a difference,” she says, “was that my graduate work started about the time of World War II, and I think I had some opportunities then that I might not have had otherwise.“The men weren’t available. Nobody was thinking about discrimination that much at that time. I wasn’t expecting it, I wasn’t looking for it, and I wasn’t thinking about that.”

What would she tell teenage girls living in Adrian today — girls who want to become scientists?

“I’d tell them to go ahead and start out and do what they want to do — do what you have in mind and don’t worry about things that haven’t happened. I think if you start out with the attitude that ‘this is what I want to do,’ why, I think the main thing is to work hard at it and put your full mind to it and don’t look for problems.”

Helen Laura Foster shared memories of her work in an interview. The primary source was Robbie Rice Gries, “Anomalies: Pioneering Women in Petroleum Geology, 1917-2017” (2017), which contains an extended account of Foster’s life.

Linda Johnson - 1969 BA in Sociology

I loved reading the history of Helen Foster – and her pursuit of a dream in the outdoors, such as geology..

I have a friend, David Lowrie, who is head of the geology Dept at Wayne State University in Detroit. I will forward this write-up to his wife, Barbara Carson-McHale, who is also my friend. Barbara and I did a Women’s Radio show in the early 1970s at WDET in Detroit. We interviewed numerous women about their careers and interests – this set of stories about Helen remains very interesting. Linda Johnson, Santa Cruz, CA

Reply

Dorrit (Smetana) Marks - 1957

Impressive! You had the spunk and the energy to follow your interests and your calling.

Wonderful to know a little about you,

Dorrit Marks – 1957

Reply

James Nixon - 1971

Can you please forward my contact info to Helen. She used to visit my parents, Tom and Geneva Nixon, in Adrian when she would return from her travels. It would be great to connect with her.

Reply

Joe D - 2015

Another fascinating article, thanks for chronicling Helen’s story, James!

Reply

Neal McKenna - 2016

Wow what an amazing and inspiring life! I am energized to get back into amateur geology, and so impressed by another amazing UM alum. You rock Helen Foster!

Reply