Branching out

The Tappan Oak was located near the west side of the Hatcher Graduate Library. (Image courtesy of U-M’s Bentley Historical Library.)

You can be lonely even in a crowd, and certainly on a college campus. That’s how it was when Chayce Griffith, BS, ’16, was a sophomore at Michigan in 2013-14.

He was majoring in engineering, but he didn’t like it, and he couldn’t find the right friends.

Many nights, for company, he would drive 10 miles home to Saline to have dinner with his family. Other nights he would just wander around the Diag by himself, stopping to read the old bronze plaques on buildings and boulders. And he liked to look at the trees.

One night he stopped by the towering old Tappan Oak, between the Hatcher Library and Haven Hall. The ground was strewn with acorns. He thought about how the tree was older than the oldest of the historical markers, yet still growing. Then, without quite knowing why, he knelt down, held open his backpack, and scooped in a couple handfuls of acorns.

He took them to his parents’ house. He Googled: “How to grow a tree from an acorn.”

Following the instructions, he put 20 or so acorns in styrofoam cups, added potting soil, then set the cups in the refrigerator in his parents’ garage.

In the spring, he took them out and lined them up outside in the sun. A few months later, he had half a dozen seedlings. A year after that, he planted the seedlings in the backyard.

His dad’s lawnmower took down a few by accident. Griffith put up markers to guard the two survivors. Then he waited.

A hardy acorn

Dubell U. Arkay wrote this ode to the Tappan Oak published in the ‘Michigan Argonaut’ in June 1886. Click the image to enlarge. (Image courtesy of Wolverine Press.)

Some 250 years before Chayce Griffith was born, a hardy acorn dropped from a bur oak 40 miles west of the frontier settlement of Detroit and sprouted in the soil. The people roundabout belonged to the Anishinaabe nations — Ojibwe, Odawa, Potawatomi. By the time their children’s children were pushed off the land by American settlers moving west after the War of 1812, the acorn had become a flourishing tree, dropping acorns of its own.

Elisha Rumsey, one of the first Ann Arborites, staked a claim to the property in the 1820s. His brother Henry cleared 40 acres but left the fine bur oak alone. So did the people who took possession in 1837 and began to erect a frontier college.

By 1852, when the philosopher Henry Philip Tappan became the school’s first president, the students numbered hardly more than 150. Tappan’s biographer said “the young men … as they came under President Tappan’s personal influence as an instructor, became to a man profoundly impressed by and drawn to him.” Enrollments soared.

In 1857, Tappan hired a young historian, Andrew Dickson White, not long out of Yale. “The ‘campus’ … greatly disappointed me,” White wrote later. “It was a flat, square inclosure of forty acres, unkempt and wretched. Throughout its whole space there were not more than a score of trees … Coming, as I did, from the glorious elms of Yale, all this distressed me.”

So, without permission, White began to plant trees. Students came out to help him. Members of the class of 1858 brought in maple seedlings. Around the native oak, the tallest tree on the campus, they planted the little maples in concentric circles, and named the oak in Tappan’s honor. The president was there to thank the students for the new trees. He remarked that the maples would long outlive the native oak, which by now was a century old.

The tallest tree

This marker is set into the boulder placed near the Tappan Oak. It describes how each member of the Class of 1858 planted trees in concentric circles on the Diag in President Tappan’s honor. Click the image to enlarge.

Twenty-five years later, on June 26, 1883, 18 members of the class of 1858 returned to Ann Arbor for a reunion. Next to the oak they set a boulder to memorialize Tappan, who had died just a year and a half earlier. To his widow, Julia Livingstone Tappan, they wrote: “Today we have visited our old haunts to find much that is changed. The growth of the university has been a thing remarkable. But all this time men have only been building on foundations laid and ideas conceived by President Tappan.”

Andrew Dickson White had long since gone off to become the founding president of Cornell University in his native New York. In 1911, now an old man, White came back to Ann Arbor to inspect his trees. Around the Tappan Oak, he counted the surviving maples planted by boys in the class of 1858. Many of them had gone off to southern battlefields in 1861. White was heard to say: “There are more trees alive than boys.”

As the Univerity grew, the limbs of the Tappan Oak sent out new twigs every spring.

It was a landmark and a meeting place, though not always in ways worthy of fond nostalgia. Every spring for decades, members of the senior honorary society called Michigamua, in keeping with its faux-Native American motif, initiated new members at the base of the oak, where they doused the newcomers with water and smeared them with red brick dust — the “red” equivalent of “blackface.” The dust seeped into the bark to a height of six feet or so, staining it the color of rust.

Arborists with saws

On Nov. 23-24, 2021, arborists felled the beloved Tappan Oak. See more photos at the University Record. (Image: Michigan Photography.)

The tree lived on for decade after decade as construction crews built and rebuilt the neighboring General Library (now the Hatcher Graduate Library), dug tunnels for pipes through neighboring soil; laid concrete sidewalks above its vast root system. The clean air and rain of the 1800s took on the taints of the industrial 1900s. But the tree stood through World War I and World War II, through the 1960s and the coming of a new century. On a day unknown to anyone, it passed its 200th birthday. The groundskeepers planted more trees every year. By the 21st century, there were 15,000 trees on the campus.

One day a microbial invader broke in through a cleft in a root or a branch. It multiplied and spread. By the 2010s, there was rot in the core of the trunk. The tree was weakening. A branch or two fell. Arborists did their inspections and shook their heads. The University couldn’t take the risk of giant oak branches raining down on passers-by, or that the tree would keel over into the Hatcher Library in a windstorm. It would have to come down. The arborists came back with saws on November 23.

Because of the rot and abrasions from saws, it was hard to get a definitive count of the rings. But it looked like about 250.

There was mourning among those who admire the campus’ trees and especially among staff members who keep watch over the University’s “public goods” in its many libraries and collections. Surely, they said, the Tappan Oak would not become a mountain of mulch — would it? They had ideas about how to keep the tree alive in memory and even in physical forms — possibly sculptures by students in the Stamps School of Art & Design, or fine furniture to be used on the campus.

They were soon assured there would be careful deliberations about what to do with the salvageable wood of the tree, now safely stored on North Campus. No formal decisions have been made, said Michael Rutkofske, the campus forester, but the plan is for the wood “to be used in university buildings, university projects or university research.”

Direct descendant

Chayce Griffith has been nurturing this four-foot-tall sapling from an acorn dropped by the Tappan Oak. Stay tuned! (Image: Caeley Griffith.)

When Chayce Griffith heard about the Tappan Oak, he had his own idea.

He had graduated from Michigan with a degree in chemical and environmental engineering in 2016. But he had no aspirations to make that his career. He decided instead to work with trees. He entered the master’s program in horticulture at Michigan State and began to study apple trees.

He got in touch with Rutkofske and told him what he had done with the acorns. Now, he said, there were two sturdy oak saplings in his parents’ backyard, growing well in the native soil of Washtenaw County — direct descendants of the Tappan Oak. They were about four feet tall.

Would the University like to have one of them?

The answer was yes.

“I couldn’t believe it when Chayce contacted me; I think my jaw is still on the floor,” Rutkofske told me. “We all agree that it’s an incredible story and a tremendous opportunity. We are currently working on facilitating his donation and focusing on logistics and timing.”

Griffith expects to complete his master’s program in 2022. Then he’ll keep going in apple research or start his own orchard.

“But if U of M decides to create a position for a ‘Sentimental Tree Replacement Caretaker,'” he said, “I’d apply.”

Sources included Karl Longstreth, Aprille McKay, Cathy Pense Garcia, Jane Immonen, Michael Rutkofske, Chayce Griffith and “Professor White’s Diag,” University of Michigan Heritage Project.

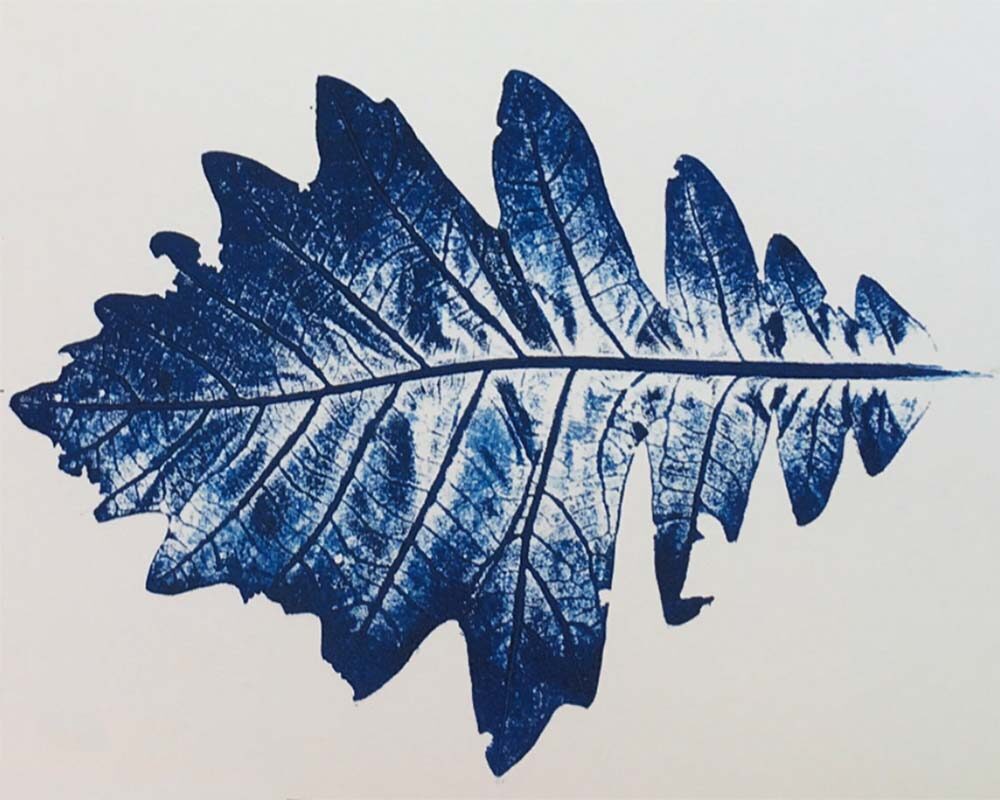

About the lead image: In 2017, as a way to commemorate the University’s Bicentennial, Fritz Swanson, a lecturer in the English Dept.’s writing program and director of the Wolverine Press, found Dubell Arkay’s poem (showcased above) using the Hathi Trust archive. A team at Wolverine Press set the poem in Artcraft 12 pt and printed blanks. Then, on the day of the commemorative event on the Diag, they asked the grounds crew to gather leaves from the Tappan Oak. He says, “We inked up both sides of the leaf, put it between two poem blanks, and ran them through the press for pressure. This produced a print of both sides of the leaf. That tree meant a lot to me personally, and to so many people on campus. Thank you for inviting me to celebrate it again with these prints. Best, Fritz Swanson.”

James Stout - 1961

I love Trees and as we all know optimists have babies and plant trees. Thanks for the wonderful story….JRS

Reply

Ric Woodward - 1974

Yes. A great story. I’ll just add that the underplanted maples we’re brilliant. Not only natural as succession, but maples pump water from below and share it with whoever is growing nearby. If your skeptical about this, observe the growth around maples during a summer dry spell.

Reply

Jon Himes - 1969 BS; 1973 MED

I am a U of M Grad and lived in Ann Arbor from 1958-1973. My father was also a UM grad and Professor of Architecture 1958-1977 ( i believe). I now am retired and live in the Upper Peninsula. I am a Wood Turner and would be happy to make a bowl, platter or vase from this wood and donate it back to the University. If this is possible, please contact me at the above email address..

Reply

Michael Pollard - 1969

Marc’s skill is superb as a wood craftsman and should be given a segment of the Tappan Oak to create a beautiful vessel for the University collection. He has earned national recognition for his work.

Reply

Nancy Creason - 1977

what a wonderful story, thanks.

Reply

David Roadhouse - 1966

I am a tree lover dating back to my early childhood in Ohio 70 years ago. In my family’s backyard we had a magnificent silver maple. It was perfect for a seven year old to climb 40 feet to tower as Tarzan. At the top, I

became king of the jungle, master tree climber. I could ascend and descend it seemed in seconds. I became

a monkey. Later in high school during a party night on Spring break on the boardwalk in Daytona Beach I bought

a squirrel monkey. I recognized a twin and it all began in that magnificent maple in Ohio.

Reply

Robert W Wilson - 1965

Wonderful story, thanks.

Reply

Leslie Wilson-Ehman - 1975

Lovely article that brought me back to the living part of campus that I always loved.

Reply

Philip Balkema - LSA ‘65: Law 68

Thank you for telling the great oak’s story. I’m pleased that an offspring will return to campus so the legacy can continue.

Reply

Lowell Getz - 1960 Ph.D

We have a similar story at the University of Illinois. Near our General Library is a large sycamore tree. It was already a sizable tree when the University was founded in 1867. It, too, has been undergoing aging problems. The center of the tree rotted out several decades ago and was replaced with reinforced concrete. Several limbs are weakening and are now supported by steel cables anchored to the main trunk. Now, a few limbs are dying. The Grounds people are doing everything they can to maintain the sycamore, a silent witness to the growth of the University.

A personal note. Although I obtained my Undergraduate degree at The University of Illinois and was on her faculty for 28 years, my Ringtone is “The Victors.”

Reply

Warren Rosenblum - 1999

We are way too quick to cut down old trees. Lawyers, rather than arborists, seem to get the final say. The odds of a branch falling on some poor student were awfully slim, and, as the Illinois story reminds us, there are ways to bolster these trees.

Very sad to hear of an old friend’s demise.

Reply

robert reed - Ph.D. '79

Yes, most of the supposedly ‘diseased’ trees can be saved with applications of various botanical bacterial counter measures. Surprised the School did not turn to Yale’s forestry folks for help. Would have saved that tree. Unfortunately most facilities departments are not composed of knowledgeable folks. Most likely a lot of that cut wood now is being used as firewood. Sad, to say the least.

Reply

Steve Gold - AB, English Language and Literature, 1969; MPH, Human Nutrition, 1975

The trees of Ann Arbor for many who have lived there are nearly as significant as the people. Trees on Central Campus like the Tappan Oak, trees in the Arb, trees along the shady streets – I remember literally hugging a huge oak on Lincoln south of Hill Street, drifting home in the small hours from a smoky, boozy party circa 1970 – they help in multiple ways to create the atmosphere of the place and time. Tobin’s wonderful story leads me to reflect on how trees span generations, stay solidly there in their quiet there-ness for life after life. I tell my little granddaughters how I used to lie on the shaded grass near the Grad Library, holding an acorn or a fragment of sandwich in my outstretched hand for the squirrel bold enough to come and take it from me. Maybe twenty years from now Lilah or Ruthie or Sierra will do the same, risking a bite to feed the many-times removed descendant of my Sixties squirrels, under the spreading canopies of the exact same trees that were there for me and the squirrels half a century ago. The Tappan Oak is gone, but its germ will live on as a mighty oak on Central Campus. I’ll be gone, but my granddaughters will live on as mighty women here or somewhere. Thoreau says we stand always “on the meeting of two eternities, past and present, which is precisely the present moment.” Reading James Tobin’s story has made this morning an excellent present moment for me, and I’m grateful.

Reply

Gary R. Frink - 1963 December Law

Congrats on a lovely essay.

Reply

Steve Gold - English, 1969; Human Nutrition, 1975

Thanks Gary.

Reply

James Tobin - 1978, 1986

Editor Deborah Holdship: Please sign up Steve Gold to write more for Michigan Today!

Reply

Ruth Watts - 66

The Tappan Oak was touchstone of enduring promise for me, a student 63-66 during the turmoil of war protests, assassinations, freedom marches and women’s rights. There were bombings, burning of draft cards, no women’s sports but change too! The Vietnam Teach In, the elimination of hours for women, and the legacy of the Peace Corps. I’m glad I was at Michigan!

Reply

Virginia Sapiro - Ph.D. '76

This is a lovely story. My parents (attended late ’40s) and my grandfather (Law1908) would have thought so, too.

Reply

Ruth Fisher Watts - 66

Just a PS. My grades suffered during 63-66 , but my education didn’t. I taught at Tappan School for many years. I was in the first class of Nationally Certified Teachers. Charles Watts MD and I were married in 66. He was MI/MI. We raise our children in Ann Arbor. He was at the Med School and handed our daughter, Sarah her MD degree at graduation! She is a 4th generation MD at Michigan! Chuck and I still have our football tickets. We have been married for 55 years! Go Blue

Reply

Ralph Edwards - 1963

My Father Percy A Edwards E1924 and Grandfather Randolph Thomas “Tom” Edwards B.Ph. 1879 would have walked by the tree many times.

Reply

Deborah Holdship

I love that so much.

Reply

Monica Fedrigo - 2001

This is so wonderful! Thank you for sharing a great story.

Reply

Tricia (McGilliard) Hedin - 1975

Wonderful article bringing back memories of the tree and campus, including the difficult tree identification class I amost failed. I also recall the peaceful solitude of sitting near the tree. I hope the salvaged wood will be made into a work of art or perhaps benches for future students to find rest and time to dream.

Reply

Kenneth Schepler - 1975

How appropriate that an MSU grad student is providing the replacement tree for UofM. me: MSU-1971, UofM-1975

Reply

Stuart Fwldstein - 1960; 1963

A few years ago the university gave some wood from a felled campus maple to various area wood turners. They made bowls and other decorative objects which were then offered for sale in the art museum gift shop. We bought one during a campus visit. Now a piece of the university graces our display shelves.

Reply

Camille Serre - 1968

Thank you for writing this wonderful story, James Tobin. And a double thank you, Chayce Griffith, for sprouting those acorns!

Reply

Jil Gordon - 1974

From an alumni family (9), first on campus in 1944 and continuing today (a sophomore), we believe and cherish history and tradition. What a wonderful story shared with all. Thank you Chayce for nurturing “the M roots” from those acorns because “Those who stay will be champions”. Thank you Michigan Today and Mr. Tobin for this article.

Reply

Jared Cantor - 2006

I have many, many fond memories of walking this area of the diag and gazing up at that majestic tree. I count myself fortunate that at some point I had stopped and read the plaque and thus knew its real significance to UM. I feel like there is also a plaque somewhere in Angell hall that also mentions the tree and those maples planted around it, some/most of which were sacrificed to the continuing expansion of Angell hall and those surrounding halls. Anyway, this was a wonderful story and it has inspired me to go look through long-forgotten photos, taken on a Palm Pilot Treo 650, I believe, of a friend of mine trying to interact with the many squirrels who loved the tree and that area of campus.

Reply

Christopher Bell - 1973; MSW 1994

Sometime in the spring during my undergraduate years I recall walking by the initiation ceremony carried out by members of Michigamua. I had no idea back at that time what group was involved, and I just figured it to be some fraternity hijink.

Years later I learned that it had been Michigamua and that a brave Nishka woman had subsequently filed a complaint sometime in the 1970s that ended Michigamua’s public ceremonial activity. Afterward, their ceremonies were then conducted in either the secrecy of their Michigan Union tower “wigwam” or their “stomping grounds” between Matthaei Botanical Gardens and Radrick Farms golf course. Subsequent complaints by Native American students, staff, and faculty finally resulted in the removal of Michigamua from campus and, ultimately, the end of their name Michigamua.

During subsequent walks through the diag over the years my wife and I would always admire the Tappan oak and see the permanent red clay stain on its trunk. Much in the way of human activity has occurred and been forgotten during the life of this magnificent tree, and now we see the passing of this silent witness. Glad to see that some of its progeny will endure!

Reply

Phillip Bokovoy - 1982 (but class of 1979)

Jim,

What a wonderful story! Good to see you still writing about Ann Arbor and UM history. Hope to see you at the next Daily reunion.

Reply

Don Nelson - 1959,1961, and 1983

Great tree story for tree-lovers like me. From 1955 to 1957 while sitting on my foot locker, I studied all forestry schools in the process of deciding where I would go after my release from the Army. I selected Michigan because it had the largest graduate enrollment and its faculty had written the largest number of forestry text books. I learned forestry and wood science from Davis, Spurr, Graham, Baxter, Gregory, Sharpe, Carow, Preston, and Ellis. I learned economics and business from cross campus faculty. Grant Sharpe taught tree identification using on campus trees such as the Tappan oak and other species in the Arboretum. On one trip to the Arboretum, Dr Sharpe and we class members surrounded a tree to be identified, under which rolling on the grass was a forestry graduate student “entertaining” his girl friend so vigororously that he did not at first realize that he and she were surrounded by us forestry students. “Go Blue” we called out.

Reply

Peter Rogan - 1977

Faith in the future is planting trees you will not live to see reach full growth. So it has been with the University of Michigan. Let it be so with the Tappan Oak, and all who are inspired by its story.

Reply

Heather Davis - 1976, 1977

Thank you for a beautiful story!

Reply

Carol E Fletcher - 1960, 1999 (yes, those numbers are correct)

I once heard a story that a boy asked his grandfather how many years it took an oak to grow. Grandfather said it was many. The boy replied, then we better get started planting. My exact sentiment every time I plant a tree. What an uplifting story about the Tappan oak and its “children”.

Reply

Randy Milgrom - 1978

I never imagined that a story about a tree could make me weep, but here we are.

Reply

Randall Smith - M ‘71

Bump Elliott once hung in effigy from this powerful symbol now gone. Thousands have walked beneath its towering branches. Michener’s Lame Beaver states, “Only the rocks live forever.” So wonderful that a graduate saved a copy to be enshrined somewhere hopefully close by the parent’s home. Thank you for the update and please follow this tale for those of us far from UM.

Reply

Robert Pleznac - '67, '71

A wonderful story. The giant old oaks that still tower over S Michigan central cities are declining in number and are too often replaced by species like Norway maple. The old oaks that remain serve to remind us that much of s. Michigan’s cities were built on oak savannas/plains, oak openings and open woodlands. Land conservancies and like minded groups would do well to get acquainted with city foresters and arborists to see if those folks would plant native oaks where appropriate if funds are made available to support this effort. How prescient—planting acorns from the Tappan Oak! I live in Kalamazoo where a few dozen huge oaks, mostly bur oaks, majestically persist, reigned over by the monster bur oak on the grounds of the Kalamazoo Institute of Arts.

Reply

Chris Campbell - 1972 (MA); 1975 (Law)

We need the big old trees to remind us that we’re relatively transient creatures and we need the new trees for the same reason. And James Tobin? Well, we need him to tell us great stories that enrich our lives.

Chris Campbell

Reply

Chris Bell - 1973; MSW 1994

Well said, Chris Campbell

Reply

Doug Brook - 1965, 1967

A wonderful story about Tappan Oak. but there was no need to editorialize in the paragraph describing the annual public Michigamua initiation at Tappan Oak. Could you not have simply written that Michigamua initiations involving the application of water and brick dust took place there in many years past and thus the bark of Tappan Oak even today appeared to have a red color? The inference that over decades hundreds of student leaders and thousands of student onlookers were involved in “blackface” is both wrong and offensive,

Reply

James Tobin - 1978, 1986

Mr. Brook: Thanks for your note about Michigamua. You and I may agree that “redface” and “blackface” are not morally equivalent, but many Native Americans argue otherwise, and it’s no easy case to make. I say that as the son of a Michigamua “sachem” (1941) and as a member of the “tribe” myself, very briefly, in 1977. (I reflect on these matters in an essay, “Remembering Michigamua,” that appears in my book, “Sing to the Colors: A Writer Explores Two Centuries at the University of Michigan” [U-M Press, 2021].) In any case, I don’t think I could have said that Michigamua initiates were painted red without mentioning that the act is now controversial, to say the least.

Reply

Stanley Levy - '55, '59','64

Telling the whole story of Michigamua would have been a contribution. For generations when persons of color and those from minority religious groups

were included as equals – when the Big U had quotas for each – would have lent to some insight of what that array of students sought to do in their senior year – make the University of Michigan a better place.

Reply

Steve Erskine - 2005

Silence is Consent

Reply

Lois Miller - staff

Thank you for writing and sharing this unique Tappan Oak story, James. Wonderful choice, Chayce! Can’t wait to see what Mr. Rutkofskee and the team do with the sapling. My heart is warmed.

Reply

Marilyn Bianco

What a story but sad, save 🌳 🌲 trees.

Reply

George Fonin - 1971 MBA

Thank You, Michigan Today, for historian James Tobin’s, “The Tappan Oak: A tale of life, death, and rebirth,”

historical recollection that in 1858, Andrew Dickson White and students named the native oak, tallest tree on campus, in President Henry Philip Tappan’s honor. And, that in 2013-14 with his good nature, student Chayce Griffith gathered Tappan Oak acorns, two of which he has nurtured to four foot sturdy oak saplings,

now offering one to Michael Rutkofske, the campus forester, to plant and carry forward the strong life spirit of the Tappan Oak and University of Michigan.

And, so heartening that the Tappan Oak tale brings back my recollections of the treasured trees at the center of the campus by the old physics lecture hall and West Engine when I was there in the 50’s. I loved to see the great trees then and have for a lifetime when visiting the campus. I am grateful that the University community values and carries forward the strong life spirit of the Tappan Oak and all the majestic natural landmarks of the University of Michigan.

Reply

Mike Kruger - 1984

Many thanks for a much more uplifting story than this one in the New York Times today (about a 250 year old Black Walnut). https://www.nytimes.com/2022/01/24/opinion/trees-environment.html?fbclid=IwAR2nP_jVhx5m9taoIRvmQEtre7wHA6dsoXbb5luDrSdOP722vLhowMtQzG4

Reply

Daniel E Moerman - 1863 (BA), 1965 (MA), 1974 (PhD)

I lived many years in Ann Arbor as a student, and later, as a professor at the U of Michigan-Dearborn. I loved the leafy campus, the block M (avoided by freshmen), the libraries. (I had a carrel in the library, from which I could exit thru a window into a window well, and out to the street to get a snack, a beer, then back into the library thru the window into my carrel. Terrific!) Thank you Mr Tobin. A wonderful story.

Reply

Steven Cook - 1984

I spent a lot of time at the Tappan Oak. Burr oaks are probably my favorite tree. I too picked up some acorns in 1981 and planted them in grandmothers yard 100 miles away in Muir Michigan. One has survived. Like the Tappan Oak, it is tall with one straight trunk and small branches. My cousins live there now and I occasionally drop by to see how it is doing.

Reply