Go for it

Four years ago, André Snellings, PhD ’07, took a longshot on his career.

“For a good part of my adult life, I was a neural engineer who did sports writing on the side,” says the 44-year-old Snellings. “These days, professionally, I am a sports analyst and writer who does some neural engineering on the side.”

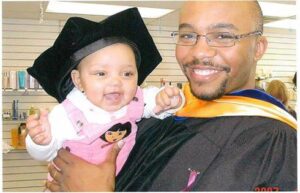

Snellings stepped away from his 16-year career as a biomedical engineer to accept a dream offer from ESPN. (Image courtesy of Snellings.)

He made the tough call in 2017 to step away from his 16-year career as a biomedical engineer and to accept a dream offer from ESPN to write full-time about fantasy basketball and NBA analytics. Snellings had been dabbling in fantasy sports for years as a columnist and blogger, a well as contributing to several fantasy sports outlets.

“I am applying science to sports,” says the analyst, who crunches statistics and looks for patterns in the numbers that indicate how well an NBA player or team will perform during the basketball season and the playoffs.

“Many of my predictions are based on mathematical models,” Snellings says. “The quantitative skills I used to analyze biological data are the same ones I use to analyze sports data. But instead of writing about my scientific findings in research papers, I’m writing about my sports analysis in articles on fantasy basketball and the NBA season.”

From Buckeye to Wolverine

A native of Dayton, Ohio, Snellings grew up in “an Ohio State house.” His two cousins played football for the Buckeyes, and as a youngster he set his sights on attending OSU.

Snellings’ mother taught high school math, and his father was a huge science-fiction fan and technology geek, who often watched sci-fi movies with his son. They attended college basketball games at Miami of Ohio and followed the Cleveland Cavaliers on the radio.

“I was really good at math and science, so people encouraged me to go into engineering,” Snellings recalls. “But I didn’t attend the best schools when I was growing up, and I didn’t know exactly what an engineer did until late in high school.”He wound up studying electrical engineering at Georgia Tech and ran track. One summer he interned with a biomedical engineering professor at the University of California-Berkeley, who was using technology to detect and diagnose cancer.

“I loved being part of his experiment, because it had real-world applications I could understand,” Snellings says.

That created the pathway to graduate school at Michigan and a PhD in biomedical engineering.

“U-M had some really cool neural-engineering applications that I could be part of,” Snellings says. “So, much to my family’s chagrin, I became a Wolverine.”

For his graduate dissertation work, Snellings collaborated with three faculty co-advisors on a project using deep-brain stimulation to treat Parkinson’s Disease symptoms, such as tremors and slurred speech.

Hooked on fantasy

When he started graduate school, Snellings still had one year of indoor track eligibility left. He joined the Michigan men’s track team and competed in the 60-meter hurdles, earning a U-M Varsity letter jacket, which he still prizes.

“It was awkward because my teammates knew I was from Ohio and had been a big Buckeye fan,” Snellings says. “They nicknamed me ‘G.T.,’ short for Georgia Tech.”

Snellings also was an avid basketball fan who had played the sport his whole life. He secretly dreamed about pursuing an NBA career, but his six-foot-one stature kept him out of the pros.

At the time, fantasy basketball was not in his lexicon.

“I had heard of fantasy sports, but I had never had time to try playing them,” Snellings says.

That changed one October night while he was waiting for a friend in the Media Union (now, Michigan Union) computer cluster. For the first time, his curiosity got the better of him and he searched the Internet for fantasy basketball. He found a general manager league on the CNN Sports Illustrated website. Typically, each fantasy manager received an initial sum of pretend money that could be used to “sign” NBA players and build a fantasy dream team. If the real NBA players performed well in actual games that season, their value in the fantasy world increased, giving the fantasy managers greater trading power to acquire even better players.“I put together the team I thought would be good, and then I was hooked,” says Snellings, noting he filled reams of paper with scribbled notes about players and their stats. “I played for the whole season and made it into the top 50 out of tens of thousands of team managers. It scratched my competitive itch.”

In 2004, Snellings struck a deal with Rotowire, which provides news and tips to fantasy football fans, to cover the Baltimore Ravens in return for free access to the website. His detailed football analyses and updates impressed Rotowire’s top brass, who later offered him a part-time paid position doing fantasy basketball analysis.

Play your game

Snellings continued to play sports and to write about fantasy basketball and football during grad school at Michigan and afterward at Duke where he had a post-doctoral fellowship from 2006-11. His research focused on using neurostimulation to restore urinary function after disease or spinal-cord injury.

Then he returned to Michigan for a second post-doc in 2011. The following year, he took a job at Ann Arbor-based NeuroNexus Technologies, a U-M spinout co-founded by his former PhD advisor, to commercialize Michigan electrodes that were first developed at the University.

So by fall 2017, Snellings’ life had become pretty hectic.

“I had a wife and three children, a full-time job, and six or seven part-time sportswriting gigs,” he recalls. “There wasn’t time for sleep, and it was affecting my health.”

Unexpectedly, a golden opportunity landed in his lap.

Snellings received a tweet from an ESPN representative, who said the company was looking for a sportswriter to expand its fantasy basketball coverage across multiple platforms.

“I hadn’t thought about doing sportswriting full-time, and this position came out of nowhere,” Snellings recalls. “My wife and I talked about it, and we decided to take the chance. No one could take my PhD away from me, so if the ESPN job didn’t work out, I could always come back to neural engineering.”

The Snellings family packed up and moved from Ann Arbor to Connecticut in November 2017.

Bridging science and sports

Snellings’ dual-career success as a neural engineer and an ESPN writer/analyst has created a bridge between science and sports.

Despite his jam-packed writing and multimedia performance schedule, he often visits local schools to make presentations about his neural research projects. In the off season, Snellings keeps his biomedical engineering skills sharp by doing contract work for corporations and universities through his consulting company, Snellings Analytics.“By vocation, I still think of myself as a neural engineer,” he says. “I try to get kids interested in biomedical engineering by tying it to what they see in fictional superhero movies — the Avengers, X-Men, and Star Wars.”

The key to engaging young people in STEM careers, Snellings insists, is helping them make a connection between what they learn in the classroom and what they will be doing in real life.

“Kids want to know science is cool,” he says. “To me, it’s all about motivation and tying science to something real and exciting.”

(Lead image in Michigan Stadium courtesy of Snellings.)

Amanda Louks - N/A

Wow! This is such an amazing and exciting story! Work hard, follow your dreams and you never know what magical opportunities will show up in your life! (big smile) I love it!

Reply

Tina Guyton

A very nice article about a great man . It’s not work if you love it. 😜

Reply

Marc DeWitt

Dre, this is amazing work. Really proud of you hometeam. I’m a doctoral student 👨🏾🎓 in Higher Ed and a former algebra student of Linda Snellings at Meadowdale. Keep up the great work. Md, M.Ed. (Ed.D loading…).

Reply