The age of pandemics

In 2019, U-M’s Honorary Degree Committee contacted one of the University’s most aptly named alumni, epidemiologist and medical doctor Larry Brilliant, MPH ’77/DSc ’19 (Hon). He had been nominated for an honorary degree in recognition of several historic victories on the front lines of global public health.

A half-century had passed since the “hippie” doctor first embarked on the life-changing mission that would end the smallpox pandemic. With his wife and partner, Girija, MPH ’77/PhD ’81, Brilliant traveled to India as part of the World Health Organization (WHO) campaign to successfully eradicate the disease. Since then, he has tackled polio, blindness, Ebola, COVID-19, and now, monkeypox.

He’s been a CEO. He holds technology patents. He’s a philanthropist, a philosopher, and a former faculty member at U-M. But for all his accomplishments, Brilliant had a gap in his academic resume. So when he heard from the committee, he made an unusual request.

“I asked for [an honorary] B.A. because I never had an undergrad degree,” he says.

A pair of family deaths had interrupted his trajectory toward law school, and Brilliant never completed the final course his senior year: a thesis on ethics. (Even without the bachelor’s degree, the Detroit native earned an M.D. from Wayne State University in 1969.)

The committee told Brilliant U-M had not bestowed an honorary undergraduate degree in about a hundred years.

“So they gave me a Doctor of Science, which I am so honored to have received,” he says.

The doctor is in

On a more recent August afternoon, Brilliant, now 78, has just completed a four-hour conference call with WHO officials and representatives of the organization’s R&D Blueprint in Geneva, Switzerland. More than a thousand researchers and health professionals also participated on the call. The urgent discussion centered on setting the research agenda to determine the most effective diagnostic tests, vaccines, and treatments for monkeypox.

Brilliant remains an optimist despite everything he knows about pandemics and human behavior. (Image courtesy of Brilliant.)

WHO declared the emerging virus a public health emergency of international concern in late July. At that time, there were more than 16,000 monkeypox cases globally and 2,891 cases confirmed in the U.S., according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

The spreading virus prompted U.S. health officials to declare monkeypox a public health emergency on Aug. 4.

“There is still time to stop monkeypox, and we have the tools to do it,” Brilliant says. “It is an orthopox virus and a cousin to smallpox, although so far, it is less lethal. We have eight or nine vaccines that may work against both diseases. We are very close to sorting out which vaccines should be used under what circumstances for people with varying levels of exposure and immunity.”

For a world still reeling from nearly three years of the deadly COVID-19 pandemic, that’s good news. But it may be short-lived. Other killer diseases are already in the pipeline, Brilliant says.

“We are living in an ‘Age of Pandemics.'”

Blessing or curse?

Modern advances are partly to blame for the proliferation of pandemics, Brilliant says. But these innovations also help stem the tide of deadly pathogens.

“Modernity has been both a curse and a blessing,” he points out. “It has allowed us to expand our population and extend our built environment around the planet, but in doing so, we now have humans and animals living in each other’s territory. We’re seeing the emergence of animal-originating viruses such as bird flu, swine flu, Ebola, SARS, West Nile Virus, MERS, and Zika that didn’t exist in human consciousness 30 years ago.”

At the same time, modernity has provided the medical profession and public health community the tools to prevent and treat many of these highly contagious diseases.

“Who would have thought that mRNA vaccines and monoclonal antibody treatments for COVID-19 would be available in just one year,” Brilliant says. “Or that antiviral medicines such as Paxlovid would come out in two years and prevent so many people from being hospitalized and dying.”

Technology also is a critical weapon in the fight against pandemics. Satellites now identify empty parking spaces in front of hospital emergency rooms. Consumers can choose from several mobile apps to check their blood pressure, heart rate, and temperature and identify possible coronavirus symptoms. Zoom calls have extended the reach of harried physicians and now provide a virtual safety net for their patients.

But, says Brilliant, there’s still one thing modernity cannot provide: trust in public health and public will.

“Trust is earned with great difficulty and lost with the least carelessness,” he explains. “If we don’t have trust and public will, we can’t do anything, no matter what tools we have. And that puts a thumb on the balance scale in favor of the virus.”

‘Never give up, never give in’

Brilliant, a former associate professor of epidemiology at U-M, has worked tirelessly, sometimes in the face of daunting challenges, to respond to global health threats and to ease human suffering worldwide.

He recounts his adventures in his 2016 memoir Sometimes Brilliant (HarperOne) and The Management of Smallpox Eradication in India (University of Michigan Press, 1985). Both publications resonate with the same theme: “You can never give up and never give in,” Brilliant says.

In the wake of the highly lethal H5N1 bird flu in 2005, he launched Pandefense Advisory, an interdisciplinary network of epidemiologists, physicians, scientists, and public health experts that provides pandemic and public health advice. The team travels to the far reaches of the world to help public, private, and nonprofit organizations mount safe, effective, and ethical responses to the COVID-19 pandemic and other threats.

Pandefense clients have included WHO, the Biden transition task force, the Democratic convention, the states of California and Hawaii, and the governments of Peru, Bhutan, and Mongolia.

Brilliant recently started the Pandemic Response Organization, which provides pro bono advisory services for schools, religious groups, homeless organizations, and local governments.

Another Brilliant-initiated nonprofit is the Seva Foundation, which he and Girija created in 1978. Since its launch, the organization has restored eyesight to 5 million people and continues to provide vital eye-care services worldwide.

Building awareness

Brilliant has devoted much of his career to building corporate and government awareness about threats to public health. He is a CNN medical analyst, a podcaster, a contributor to Foreign Affairs and The Wall Street Journal, and a guest lecturer at U-M, Oxford, Harvard, and other universities.Over the past 25 years, he’s held leadership roles in advocacy, philanthropic, and venture-investment organizations ― such as Google Foundation, Skoll Foundation, the Skoll Global Threats Fund, and Ending Pandemics ― that are dedicated to addressing pandemic preparedness, climate change, water security, and other global challenges.

Former President George W. Bush tapped him as the founding chairman of the National Biosurveillance Advisory Subcommittee in 2008. The epidemiologist also joined the World Economic Forum’s Agenda Council on Catastrophic Risk and was a “First Responder” for the CDC’s bioterrorism response effort.

Learning from the past

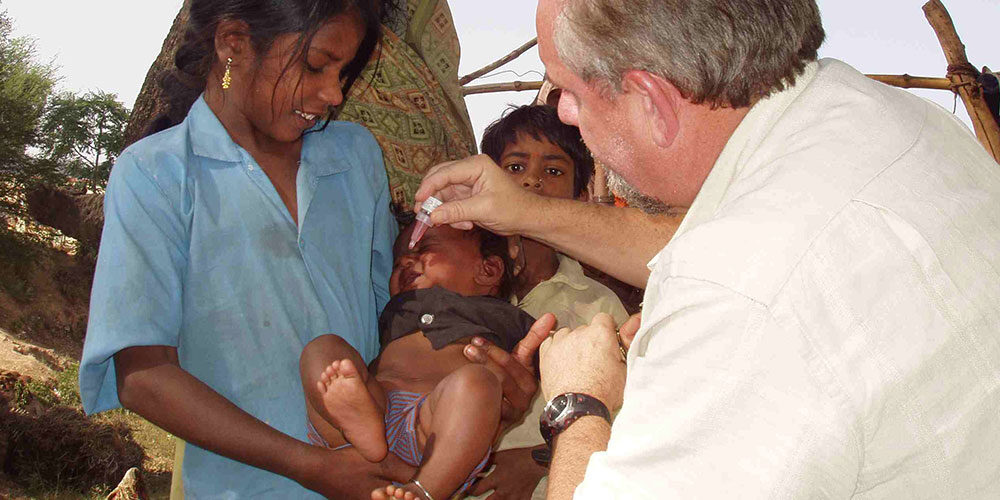

Brilliant with a smallpox-infected child — one of the last — near Tatanagar, 1978. (Image credit: Ned Willard, courtesy of Brilliant.)

Brilliant recently donated his WHO India smallpox campaign archive to U-M’s Bentley Historical Library. Sixteen large cartons contain more than 60,000 documents, as well as photos, microfilm, and CDs documenting the team’s down-in-the-trenches efforts to stomp out the last vestiges of smallpox in India in the 1970s.

“This archive will be a lesson for researchers forever because smallpox is the only disease we’ve ever eradicated,” Brilliant says.

The archival trove includes reports of every smallpox outbreak in India’s final campaign. In addition, it details the team’s work in mounting a surveillance system, identifying and reporting cases, conducting contact tracing, and aligning the divergent interests of national governments, state health departments, and religious groups.

“The anti-vaccine movement in India during the smallpox campaign was more ferocious than it has been here in the U.S. during COVID-19,” he says, explaining the smallpox vaccine is made from a poxvirus that infects cows. In India, it’s a sin and crime to kill a cow.

“The only way to stop the anti-vaxxers was to bring all the religious groups together to talk through the issue and hope that good people of faith would conclude that a human life is more important than a cow’s life,” he adds.

Looking forward

Proud Wolverines Girija Brilliant and Larry Brilliant at the Golden Gate Bridge. (Image courtesy of Brilliant.)

Brilliant sees himself as a futurist who draws on lessons learned from the past as he pushes for progress.

“My job has always been to look around the corner,” he says.

Brilliant is also an optimist committed to strengthening the public health care system, locally and globally.

“Public health has lifted the suffering from so many diseases off our shoulders,” he says. “I saw thousands, mostly children, die from smallpox, a disease that killed half a billion people in the 20th century. But now it’s gone because of the work of brave health workers. How can you not be an optimist?”

Brilliant is confident public health professionals will one day declare victory over COVID-19.

“It may seem like it’s taking a long time to outwit COVID, but we will defeat it,” he insists. “And in retrospect, it will look like it happened in the blink of an eye.”

(Lead image: Brilliant administers a polio vaccination in India, 2005. Image courtesy of Brilliant.)

Steven Newman, MD., FAAN, FACP - ‘70 UMMed, ‘71-‘73 Res, ‘73-‘75 Fellowship

Having followed Larry’s unorthodox recitations since sitting across a table several times a week, during our formative preadolescent years, even then presented a unique, unconventional and unforgettable presence. His professional progression has proven the value of his ethical stance these last 6-1/2 decades, deserving of all humanitarian recognition.

Reply

David Hirt - 1969

I’m proud to have known about Larry from our Mumford High days in Detroit.He was a year ahead of me. I would see him occasionally as he was a a close friend of Jerry Eichner, another distinguished physician who grew up a few doors from me on Cherrylawn near seven mile road.

I learned how Larry and his family survived an unbelievably close call with organized crime only recently after reading Sometimes Brilliant.

Thank you for this excellent article about a wonderful human being.

Reply