“A fragment from the heart”

In 1943, at the age of 47, an unheralded writer named Betty Smith published her first novel, a semi-autobiographical account of an idealistic young girl fighting to survive poverty and family strife in early 20th-century Brooklyn.

Smith’s debut, A Tree Grows in Brooklyn, sold three million copies in its first year. It was the bestselling novel of 1944 and the most popular title of the government’s Armed Services Editions, distributed to Americans serving in World War II. Hollywood made a movie in 1945, starring a young Peggy Ann Garner (above). The New York Herald-Tribune’s reviewer wrote: “If ever a sensitive, expressive young woman offered you a fragment from the very heart and fabric of her being, it is Betty Smith writing A Tree Grows in Brooklyn.”

One might say Smith discovered that very heart and fabric of her being in Ann Arbor, where she lived with her first husband. It was here in the 1920s that she encountered playwright and professor Kenneth Thorpe Rowe (1900-88) while “spying” on his class one afternoon. Rowe invited her to audit his playwriting course, encouraging the aspiring novelist to “write what you know.” Smith, who had lived hand-to-mouth for much of her life, took his words to heart.

One-hit wonder

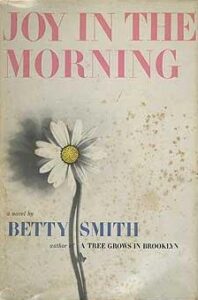

The success of Smith’s debut novel brought money, fame, and a new lifestyle. She was invited to give speeches and address conferences. She published a second novel in 1947 and a third in 1958 but never reclaimed her initial success.

Meanwhile, her personal life was beset with trials. Her first two marriages ended in divorce. A third husband died in 1959. As the 1960s began, she was living in Chapel Hill, N.C., and yearning to immerse herself in a new writing project.

She returned in memory to the early 1920s in Ann Arbor, where she had spent the initial years of her first marriage to a U-M law student. The ruminations inspired Joy in the Morning about a young wife struggling to balance her obligations to her husband with her obligations to herself. It’s about discovering happiness in the little things, despite life’s larger challenges.

And there’s another timeless theme specific to college life: On a college campus like Michigan’s, in whatever era, one will always find a stratum of less privileged people trying to “pass” in the dominant crowd. However successful, they never feel they fit in. So it is with Betty Smith’s young alter-ego, 18-year-old Annie Brown, in Joy in the Morning (Harper & Rowe, 1963).

From Brooklyn to Ann Arbor

Born Elizabeth Wehner to Austrian immigrants, Betty Smith grew up poor in the Williamsburg section of Brooklyn. As a girl, she took refuge in books from the public library and in her own writing. But she dropped out of high school to go to work. Indirect evidence suggests that as a teenager she was sexually abused by her stepfather. At 22, she fled New York for Ann Arbor to marry her Brooklyn boyfriend, aspiring lawyer and U-M student George Smith.

With scant savings and no family support, they barely pieced together a living, sometimes running short of food. Between classes and studying, George earned a paycheck as a janitor, then as a grocery clerk. He rose early to deliver The Michigan Daily. He became the caretaker of the athletic field later named Elbel Field.

To earn her high school diploma, Smith enrolled at Ann Arbor High School on East University (now the School of Education). In the afternoons she worked as a “counter girl” in a restaurant and as a store clerk. The couple moved from a boarding house to an apartment on Forest Avenue, then to a small house on Hill Street. Two years after arriving in Ann Arbor, Betty gave birth to the first of two daughters.

Life among the coeds

Smith said later that she intended Joy in the Morning to show that struggling when young is not so bad as long as one has hope.

She also said: “I wanted to write a sunny book about sex, not a sexy book.” But in fact, the novel was neither very sexy nor very sunny. It does have a strong narrative drive, though, that arises from Annie’s effort to pierce the invisible barrier separating her from the well-fixed and carefree “coeds” on campus. She looks like them. But she is not like them, as the following passage reveals:

“Most wore what was almost a uniform: dark pleated skirts, loose pull-over sweaters, a string of ‘pearls,’ saddle shoes, and socks. I’ll never be one of them, she thought sadly. I’ll never belong.

“Just to think, she mused, some people are born to this. Before they’re a day old, even, it’s fixed that they live in a place like this; fixed that they go to college…

“Annie envied their casual ways, which came from bred-in assurance. She envied the way they dressed; plainly, but expensively. The costly sweaters, the good shoes… She thought of her lack of education; of her wrong use of words; of her mispronunciation of words she knew; of her grammar… She got up and went away.”

A drive to learn

Despite her seeming deficits, Annie possesses something the coeds are supposed to have but don’t — insatiable curiosity and the drive to learn.

When her husband Carl lends her his library card, Annie climbs the steps of the General Library and walks “from room to room, floor to floor, stack to stack… She loved books. She loved them with her senses and her intellect. The way they smelled and looked; the way they felt in her hands; the way the pages seemed to murmur as she turned them. Everything there is in the world, she thought, is in books.”

She checks out War and Peace, then Crime and Punishment, and absorbs the great dramas long into the night, much to Carl’s frustration.

One day, Annie passes the open door of a university classroom and hears an English professor discussing literary realism. She listens from the hallway. She returns each Tuesday and Thursday, then begins to write the assignments, sight unseen. The professor eventually discovers Annie and invites her to audit the course. When she turns in her first paper, he reads it aloud and praises it. Before long Annie is auditing courses in playwriting.

Drawn from her own life

Kenneth Thorpe Rowe would be an unofficial mentor to novelist Betty Smith. (Image courtesy of U-M’s Bentley Historical Library.)

Like much of Joy in the Morning, these events were true to life. As a “special student,” Betty Smith learned from Kenneth Thorpe Rowe, the same renowned teacher who would mentor playwright Arthur Miller, movie director Lawrence Kasdan, and many others.

So Ann Arbor was crucial to Betty Smith’s life as a writer, but not because of the events that inspired Joy in the Morning, which was published to mixed reviews. It was because she met and worked with Rowe, who taught her the elements of story construction and encouraged her to write about events drawn from her own life.

In Rowe’s class, Smith began to find the story that would shape her first novel. It began as a play about a Brooklyn girl named Francie Nolan and received Michigan’s prestigious Hopwood Award for major drama, including a $1,000 prize. The award attracted the attention of a playwriting teacher at Yale, who invited Smith to study with him. She soon wrote and sold a series of one-act plays. Then she developed the story of Francie Nolan into the novel that became A Tree Grows in Brooklyn.

Sixty years later, the novel is still beloved, outpacing works by Laura Ingalls Wilder, Herman Hesse, Ayn Rand, and W. Somerset Maugham at the booklovers’ site Goodreads.

Not long after Joy in the Morning was published, Smith was diagnosed with cancer. She died in 1972 at the age of 75.

Sources included Valerie Raleigh Yow, Betty Smith: Life of the Author of A Tree Grows in Brooklyn (2008).

Matthew Zivich - 1960

I’m proud to say I took two classes with Prof. Rowe in about 1959 and 1960. As I recall, one lecture course was held in a very large auditoreum where we were seated alphabetically making it easier for the grad student assistants to take roll. But for me, it meant a distant chair in the last row. Seated in front of me was an older student from the UK who spoke highly of Prof. Rowe but apologized for snoozing during the lectures. Prof. Rowe was a soft-spoken lecturer, diminutive in size with snow-white hair and a flat, midwestern accent. I knew virtually nothing about drama and the theater before I took his classes. I still have the text book and thankfully the knowledge gained from his lectures.

Reply

Joyce Baker Gates - 1977

Thank you so much for writing this wonderful article about Betty Smith! I watched the movie, “A Tree Grows in Brooklyn,” but had no idea about Ms. Smith’s connection to U-M. It is just a reminder of Michigan’s rich history. It’s great to be a Michigan Wolverine!

Reply

Paul Sponseller - 1972

This is a touching story about thr atmosphere of learning in Ann Arbor come and how some people come to it differently. It also illustrates the impact mentoring can have. Thank you for this wonderful piece of history.

Reply

Barbara Stark-Nemon - 1971, 1978

Thank you for this wonderful piece! I had the privilege of sitting in on several of Professor Rowe’s classes at the end of his career and the beginning of mine. Then I became his neighbor for the last years of his life. What I didn’t know was his connection to Betty Smith, whose novels were part of the inspiration for my encore career as a novelist. A treasure of connections!

Reply

Mary Marsh Matthews - 1953

The distinguished Professor Rowe was a legend when I was here as a student. When I returned to Ann Arbor two decades later with my family, he became a neighbor, though one we were unaware of. That is until my youngest child, a first-grader walking home from Angell School, was chased by an over-friendly unleashed dog and ran up onto the nearest front porch—his—to ask for help. Professor Rowe kindly took her in, dried her tears and calmed her, then telephoned her worried mom. To me, he will always be the gentle, soft-spoken, white-haired man on Day Street who “rescued” my daughter.

Reply

Don Parshall - AB1976/JD1979

I always enjoy Dr. Tobin’s “backstories” about UofM history. Interwoven w/ this story is an issue that is sadly still with us: student food insecurity.

Reply