A campus in crisis

Dr. Harley Haynes was in a dead panic.

As director of University Hospital, Haynes was losing employees by the day. Others were striking for higher wages.

Japanese high school students change classes at the Rohwer detention camp in McGehee, Ark. Some would be recruited to work at U-M.

(Image: National Archives and Records Administration. )

With America’s entry into World War II in December 1941, staff were leaving U-M in droves to serve in uniform or to work in defense plants offering bigger paychecks.

“We are very short of nurses, wardhelpers, orderlies, diet maids, kitchen help, porters, meat cutters, and grocery clerks,” Haynes told U-M President Alexander G. Ruthven nine months after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor.

Karl Litzenberg was feeling no better than Haynes. His job was to manage the University’s residence halls, and right now there were fewer and fewer hourly workers to clean dining halls and lounges, stock and organize food pantries, and prepare and serve thousands of meals.

“The situation,” Litzenberg said, “is almost calamitous.”

Faced with a mounting staff shortage that threatened to paralyze operations across campus, U-M leaders turned to an unusual source of labor: Japanese American people incarcerated in wartime camps.

New workers came to Ann Arbor from places like Manzanar, Heart Mountain, Rohwer, and other so-called relocation centers located in remote areas of the West. The camps were hastily built after President Franklin D. Roosevelt ordered the imprisonment of more than 110,000 people of Japanese ancestry from the West Coast following the Pearl Harbor bombing.

As U-M staff, American-born Japanese workers mopped the floors of West Quad, the Lawyers Club, and other dormitories. They washed dirty dishes at the Michigan Union; ferried food trays and emptied bedpans at the hospital; raked leaves outside the President’s House; prepped salads at East Quad; and carried out the daily, often overlooked, work needed to run the institution.

Yet at the same time, the University barred the door to other Japanese Americans who sought to enroll as students. Admitting students of Japanese ancestry, campus leaders said, was neither “wise” nor “desirable” during wartime because they might be traitors, or worse.

Whether as employees or prospective students, the young people were adamant about their nationality. “100% American,” wrote 22-year-old Junzo Takahashi after arriving at U-M from a camp in Arkansas.

‘Policy … is to discourage students’

Toshio Sakai in 1949, when he applied for his pharmacist’s license after graduate school in Wisconsin. (Image: Ancestry.com.)

Toshio Sakai was a victim of terrible timing.

After a freshman year at the University of Southern California, Sakai wanted to transfer to U-M’s College of Pharmacy in mid-1941. He was quickly accepted and told classes in Ann Arbor would begin at the end of September.

“Hoping to meet you in the near future,” Professor Clifford C. Glover wrote in welcoming Sakai.

Sakai ended up delaying his transfer for a year. When he had his USC transcript sent to Michigan a second time, with hopes of enrolling in mid-1942, the reception was decidedly cold.

“Had you come in the fall of 1941 as was apparently the plan when you wrote us, we should have been glad to continue your enrollment,” said Howard B. Lewis, head of the pharmacy program, “but the University does not see its way clear to extend this permission to enroll to include the next year.”

U-M’s view of Sakai, and all students of Japanese ancestry, had been clouded by war, fear, and racism.

At the same time FDR ordered the forced removal of West Coast residents considered a national threat, the University shut its doors to Japanese American students. There was no such ban on students with roots in Germany or Italy, the other Axis powers.

As a major university doing military research and located near defense plants, mainly a bomber factory outside of Ypsilanti, U-M was deemed critical to the war effort by the War Department. That status gave the University leeway to reject Japanese American students and employees alike. But it was students, not hourly workers, who were kept away.

The University viewed Japanese Americans as potentially disloyal and dangerous students, yet entrusted them enough to care for hospital patients and feed military troops training on campus. The twisted logic mirrored the national mindset. A Japanese American woman living in Los Angeles could be imprisoned, while her brother in Boston remained free; the government detained West Coast Japanese Americans while enlisting their sons in the military.

U-M turned away Japanese American students hoping to transfer from West Coast universities rather than face imprisonment.

(Image: College of Pharmacy records, Bentley Historical Library.)

A congressional commission later said the conflicting actions proved the “power of war fears and war hysteria to produce irrational but emotionally powerful reactions to people whose ethnicity links them to the enemy.”

That included action by U-M’s deans, who after “very careful thought” banned Japanese American students because “we are in the defense area which is under constant and severe surveillance by government officials,” said Registrar Ira M. Smith.

With the forced migration underway that spring, West Coast universities scrambled to find new institutions for students facing detainment. When the media hinted that U-M would accept Japanese American students from the University of Washington, President Ruthven was swift with a denial: “The policy of the University is to discourage students from seeking admission.”

John Hikaru Shinkai, a college junior teaching math and science to high school students while imprisoned in Utah, hoped to transfer. Mitz Murakami, a University of Denver student who had never stepped foot in an internment camp, wanted to be a U-M student. So did Shizuko Toyota, a University of California-San Francisco sophomore living in Utah; she applied to U-M at the same time her father, Shizutaro, was under arrest for suspicion of loyalty to an enemy nation.

They were all turned away. The University gave the same answer, over and over, to Japanese American students wanting to enroll.

“While we may have every confidence in the integrity and loyalty of individuals of Japanese ancestry, it has not been felt desirable to accept any considerable number of such students at present …”

Lewis tried to explain to a University of Washington dean.

“I realize that this decision is possibly not a just one, since there must be Japanese students at your Western universities who are entirely loyal,” Lewis said, “but the University would find itself in a very difficult position if some student admitted since December 7 should commit some serious act of sabotage or disloyalty.”

In 1941, there were 15 Japanese American students at U-M; by 1943, there were three.

The University of Wisconsin accepted Toshio Sakai. He paused his studies in 1944 to join the Army and re-enrolled after the war, earning his bachelor’s degree in 1948. He spent his career as a pharmacist in Madison, including supervising pharmacy interns from his alma mater.

‘They had nothing to do’

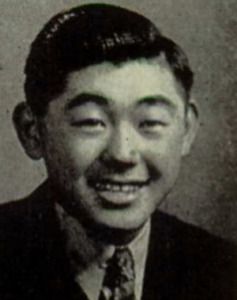

Jiro “Jerry” Kakehashi as a Gardena, Calif., high school senior in 1939. (Image: U.S. School Yearbooks, 1900-2016, Ancestry.)

The first Japanese American workers arrived on campus in late March 1943 – 27 young men from the Rohwer and Jerome concentration camps in southeastern Arkansas. Where the War Relocation Authority had established most camps in dusty, desolate locations in Utah, Idaho, Arizona, and other western states, Rohwer and Jerome were muddy, swampy places in the Arkansas Delta.

Among those arriving by train in Ann Arbor was Jiro Gerald “Jerry” Kakehashi, a University of Southern California senior. The government had uprooted him, his parents, and two sisters from their suburban Los Angeles home in September 1942. The military first held them at the former Santa Anita Racetrack, with horse stalls converted into living quarters. Kakehashi, 22, busied himself helping families set up their new homes.

From Santa Anita, the Kakehashis moved to the Rohwer camp. Jerry Kakehashi wrote letters to his older brother, George, who was serving in the Army, saying the family felt helpless but tried to make the best of the situation. When George received a furlough to visit Rohwer, he was happy to see his family but rattled by guard towers surrounding the camp. “To me it was terrible,” he said. “They had nothing to do.”

Those conditions made jobs elsewhere very appealing.

Jerry Kakehashi and all others recruited to work at U-M were known as “Nisei” (pronounced NEE-say) – American-born children of immigrants born in Japan. Those detained in the camps could request an indefinite leave if they had a place to go and a job to support themselves. Camp directors granted clearance based on a person’s perceived loyalty.

Military police were stationed at all detention centers, including Rohwer in Arkansas.

(Image: Densho Digital Repository.)

For U-M, employing captive Japanese Americans was not so much an act of compassion as it was an economic solution to a dire labor shortage. And for the Nisei – particularly teenaged boys and young men – leaving their incarcerated families for work in an unknown city and state was a brighter prospect than life in isolated camps, with tarpaper-covered barracks, rudimentary facilities, and barbed wire fences.

(Nisei workers were not U-M’s first Japanese American wartime employees. In late 1942, the War Department established the Army Japanese Language School on campus, with three dozen men and women of Japanese descent teaching hundreds of servicemen. Some instructors came from prison camps, and others from different parts of the country. The teachers – many of whom had college degrees – were considered University faculty, with higher pay and more privileges than Nisei hourly workers. The WRA called them “the backbone of evacuee morale” on campus.)

The man in charge of hiring the initial group of workers was Francis C. Shiel, who became acting director of residence halls in early 1943 when Karl Litzenberg – who had lamented the shortage of employees soon after Pearl Harbor – resigned to join the Navy.

Shiel had served for three years as the business manager of the dorm system and understood staffing needs.

Wartime housing on campus had become a game of shuffling bodies. U-M had agreed to train thousands of Army and Navy officers, who were put first in line for campus housing. So out went the freshmen and in came the officer candidates – a thousand soldiers in East Quad, 1,300 sailors in West Quad, military doctors and dentists in Victor Vaughan House near the hospital, Army engineers in Fletcher Hall.

Undergraduates had to find space in underused fraternity, sorority, and boarding houses. And all civilian students, regardless of class, were on campus year-round because of an accelerated academic year of three semesters rather than two.

From residence halls to dining rooms and cafeterias in the Michigan Union and Michigan League, thousands of people required hot meals, clean dishes, and sanitary facilities.

Not all campus leaders knew about Shiel’s initial hiring spree in Arkansas. While Kakehashi and others were already in their first weeks of work, one U-M vice president warned the Board of Regents against employing Japanese American people.

“The Japanese, even though born in this country, are of a different race,” said Shirley W. Smith, secretary of the University.

“We are at war with the country from which their more or less immediate ancestors came; Americans don’t seem to think the way they do; and the situations that might grow up after the war with little groups of Japanese established around the country might prove a problem.”

U-M recruited hundreds of Japanese American men and women held in World War II internment camps to work and live on campus. (Image: Ann Arbor District Library)

Smith’s objections went nowhere. In late April 1943, regents said it was OK to hire both conscientious objectors and Japanese American detainees, and encouraged administrators to use “their best judgment as to what course to follow.”

Jerry Kakehashi first became a storeroom clerk, stocking shelves and monitoring food supplies at West Quad. He knew the work well, having spent hours helping at his father’s grocery in Gardena, Calif.

His second job was more critical. Shiel asked the 22-year-old to join him on trips to prison camps to help enlist more workers. Recruiting in Arkansas had run dry, so Shiel now focused on camps in Utah and Idaho.

“These people are sure hard to sell a job to,” Shiel wrote from Topaz, in central Utah, in late May 1943. “We interviewed about 50 on Saturday and as of yet have not had any results.”

He added: “Everyone has accepted Jerry all along the way except for the military police, who we have to face twice in coming and going out of the camp. They are sour pusses or worse.”

Shiel and Kakehashi met at Topaz with block managers, Japanese American detainees who managed the camp’s military-style barracks, in hopes of persuading new employees.

“Mr. Shiel stated that they have plenty of jobs and a variety of jobs for single men, single women, and couples with housing provided and meals furnished in most jobs,” a secretary recorded in the meeting’s minutes. “Mr. Kakehashi believed in relocation of the evacuees and stated that the public sentiment around Ann Arbor is excellent.”

Kakehashi’s upbeat assessment applied to the first few dozen workers like himself. As more detainees arrived in Ann Arbor, the mood would change.

Continue reading These Young Americans at heritage.umich.edu. The story picks up at Chapter 4: A Difficult Social Problem. Please return here and comment below if you are so inclined.)

(Lead image is courtesy of the Ann Arbor District Library. U-M recruited hundreds of Japanese American men and women held in World War II internment camps to work and live on campus.)

Mikio Hiraga - 1955 BS/Public Health-1959 MD

My family came ro Ann Arbor in April 1944.We were in the Manzanar camp from 1942 -1944..The Sisters of Mercy/St Joseph Mercy Hospital sponsored our family’s release from camp. I remember the citizens of Ann Arbor were not totally receptive to our presence.

Reply

Kazuhiro Saitou - n/a (a faculty member in College of Engineering)

Heartbreaking. I sincerely hope the world is better now for my Nisei daughters.

Reply

Phyllis Baker - 1970

I learned little about the relocation camps in American history classes. After moving to Wyoming in the 1970’s, I learned about Heart Mountain and later about Granada. I never suspected that internees were employed so far from the camp boundaries. Or that Nisei were denied enrollment during WWII. Thank you for bringing this to our attention.

Reply

Eddie Sammons - 1982

This information detail is very interesting to me. My father was WWII veteran who learned Japanese language. He continued in USAF to retirement in 1962 in Japan, later returning to USA. I remained for a time, marrying a daughter of Japanese soldier who fought in China. I have 3 children, 6 grandchildren, and 2 great grandchildren, all residing in USA. I knew about WRA but not to the detail in this article.

Reply

Kim Hachiya

My Nisei father and uncle both left Heart Mountain to enroll at the University of Nebraska, which accepted about 135 Nisei. Their sister (and her future husband) enrolled at Nebraska Wesleyan University. That Michigan would hire but not enroll Nisei, and the attitude by the university secretary, is a sad commentary. Thank you for exposing this story.

Reply

Ted Tanase - 1963 (B.S. Engineering)

My family was interned in Topaz (Utah) and we arrived in Detroit after my Dad secured a job as an architect in 1943. My sister graduated from UM (1959) as did I (1963 – BS Engineering).

I was invited to join a fraternity that was trying to convice their national organization to allow Asians, Blacks, and Jews to become members. I eventually joined a fraternity that was “open”. But, I was impressed that there were fraternities and other organizations trying to make things “equitable”. A strong plus for UM.

Today the discrimination for Asian students is that some Universities required higher test scores (than any other race) to be admitted as a student. Thankfully, and correctly, that discriminatory policy was struck down in court.

Reply

Mark Tanase - 1991

How disappointing it is to see Michigan guilty of racism against Americans who happened to be of Japanese descent by explicitly denying them admission during the war and then not learning anything from it by continuing to discriminate against all Americans of Asian descent by requiring this group to have higher scores and grades than others to gain admission. I, for one, am grateful that this is no longer legal.

Reply

Anne Okubo - 1977 BA

All of my family were held in concentration camps. My father and all of my uncles served during WW2 while the women and children stayed in camps. As an alum of UM I had no idea that internees were employed by the University or the discrimination against JA students. I grew up in Detroit because of a government policy to spread Japanese Americans across the country, thus entitling me to attend UM as a resident.

Reply